Editor’s Note (6/1/17): This story has been updated to reflect the Trump administration’s announcement today of its decision to withdraw from the Paris climate agreement.

Pres. Donald Trump announced today that he would pull the U.S. out of the Paris climate accord. But whether Trump had kept the U.S. in the agreement or not, his policies—if they all become reality—already had the power to profoundly undermine the nation’s ability to reach the U.S.’s Paris climate goals.

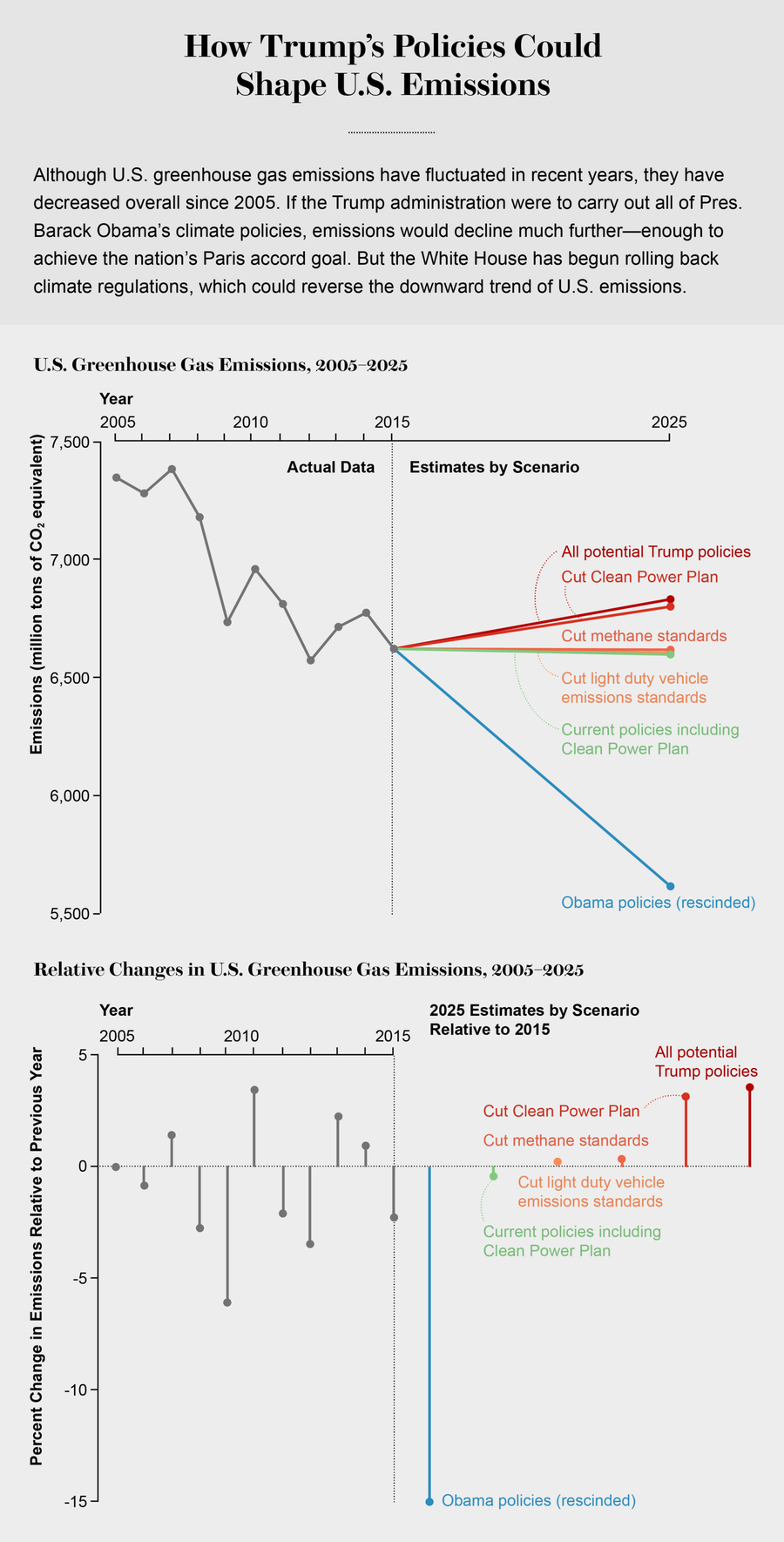

According to a new report (pdf) released by analysts at the recent Bonn climate talks, the president’s rollback of current climate regulations, if successful, could cause the U.S. to release 0.4 gigatonne more carbon dioxide in annual emissions in the year2030 than if those policies remained. That gap gets much larger when the report authors accounted for Trump’s decision to dump the Climate Action Plan, which was created by the Obama administration but has not yet been fully implemented. That would create 1.8 gigatonnes more CO2 in 2030 than the past administration had envisioned—about 31 percent of 2005 U.S. emissions. “This amounts to a very significant reversal of the downward trajectory that U.S. emissions have been on,” explains Bill Hare, one of the report authors and CEO of Climate Analytics, a nonprofit climate science and policy institute. “Under Trump's policies the U.S. will fall far short of itsParisclimate goals.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Under the accord theU.S. had agreedto reduce its emissions 26 percent to 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025. One of the major policies Trump has targeted is the Clean Power Plan (CPP), a centerpiece of Obama’s action plan. It requires the power sector to significantly reduce emissions. The plan is currently tied up in court, but if it never becomes reality, its demise would release 202 more million metric tons of CO2 in annual emissions in2025—which would cut 11 to 12 percent from the U.S.’s previously planned efforts to achieve the Paris 2025 target.

The power sector is still predicted to reduce its emissions significantly without the CPP due to the retirement of coal plants and the growth of renewable energy and natural gas. Thanks to those market forces, “we’re already reducing emissions in the power sector pretty significantly,” explains Kevin Kennedy, deputy director of the World Resources Institute’s U.S. Climate Initiative. But without the CPP, or an alternative plan, “U.S. emissions are expected to level off,” according to the report, rather than decrease.

Credit: Amanda Montañez Sources: EPA “Inventory of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks”; “Action by China and India Slows Emissions Growth, President Trump’s Policies Likely to Cause U.S. Emissions to Flatten,” Niklas Höhne et al. Climate Action Tracker Update, May 15, 2017

The report highlights other actions by Trump that could hurt U.S. climate efforts. One of those is the possible rollback of vehicle efficiency standards. If the administration weakens those regulations, the report says, passenger carsand small pickup truckswill add 22 more million metric tons of CO2 in 2025 than they would have otherwise—taking away a little over 1 percent of the U.S.’s former strategy for hitting its Paris 2025 goal. That number may sound small, but that’s because not many of the vehicles affected by those efficiency standards will be on the road in 2025. “Those [standards] are a much bigger deal as you look out to 2030 and beyond,” Kennedy says. “The nature of turnover in the auto industry is slow, so that significant reductions take more time. Part of solving the puzzle overall is how you're setting yourself up for the longer-term reductions.”

The Trump administration is also reviewing the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s regulations for methane emissions from the oil and gas industry. The EPA’s rule would have dropped CO2 emissions by an additional 9.2 million metric tons of CO2 in 2025—a little under 1 percent of theU.S.’s previously planned efforts to reduce emissions for its Paris target. Again, that number may seem trivial but, Kennedy explains, “you need to be working on methane from industry, on vehicles—across the economy—to be able to meet the [Paris 2025] target.” The U.S. also has yet to ratify the Kigali Amendment—an international plan to reduce hydrofluorocarbons, powerful greenhouse gases used in systems like air-conditioning and refrigeration. The Trump administration appears likely to ratify the amendment, however.

If all the current U.S. climate policies—including the CPP—stayed in place, they would bring U.S. emissions 10 percent under 2005 levels by 2025. Even that reduction does not come closethe U.S.’s pledge to reduce emissions 26 to 28 percent. If Trump weakens these policies, the Paris target could be even further out of reach in the future.

Obama’s Climate Action Plan was designed to go the rest of the way. The CPP and vehicle standards were central pieces but the plan contained additional policies that had not yet been implemented, such as strategies to double energy productivity by 2030.Weakening U.S. climate policies instead—both planned and current—could shift the nation’s emissions trajectory from a decline to a relative flat line over the next 10 years, Hare says.

The report also notes the U.S.’s 2025 Paris goal itself would not have kept the global temperature rise below 2 degrees Celsius, which is the central purpose of the climate agreement. Action by other big national emitters is essential. And under the accord, nations are supposed to ratchet up their emissions cuts over time.

The ultimate Paris goal is still not beyond reach for the U.S., according to some experts. “[The report presents] one of the more pessimistic views in terms of what could happen,” says Noelle Selin, associate director of Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Technology and Policy Program. For one, the president’s regulatory rollback may not even happen; rescinding or altering regulations takes time and environmental groups will almost certainly fight any changes in court. Also, economic forces are strongly influencing the nation’s emissions, notably the growth of natural gas and renewable energy paired with the decline of coal. State and local governments affect emissions as well; California, defying the White House, is pursuing its own rigorous climate regulations. “The report is a useful statement of what might happen if the Trump administration got its way,” says David Keith,professor of applied physics and public policy at Harvard University. “At present it looks like the administration’s ability to enact policy is pretty weak.” Nevertheless, Keith says, “uncertainty cuts both ways. It could end up worse than the report says.”

Keith and Selin stress that policy reversals by the administration could undermine global goals beyond the U.S.’s own emissions. “Emissions reductions depend on cooperation,” Keith explains. Right now, China and India—two of the top greenhouse gas emitters—appear set to overachieve their Paris goals, according to the new report, largely because they seem likely to decrease their coal use sooner than predicted. But as it becomes clear the U.S. is not pushing for more ambitious climate actions, Selin notes, that may lead to other nations not meeting their targets. “That’s the real impact,” she says.