In the ground beneath the first Protestant church built in English America, in a settlement partly founded to secure the New World for a new religion in the early 1600s, archaeologists have unearthed a relic that seems to belong to the wrong house of worship. Jamestown, Virginia, begun in bitter rivalry with Catholicism, has yielded a body entombed with ritual symbols that, in the Old World at that time, were common to Catholic burials.

“There could have been a group of secret Catholics at Jamestown,” says James Horn, president of the Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation, the group supervising the dig. “They may have been spies for the King of Spain, who wanted the New World for the Pope. Or was this a holdover Catholic item that was being repurposed for the new Church of England religion? These are tantalizing possibilities.”

On Tuesday, researchers announced the find, part of four graves uncovered at the site. The four colonists died between 1608 and 1610, a period of war, struggle and starvation at Jamestown. The four were Reverend Robert Hunt, the first Anglican (Church of England) minister in the colony; Sir Ferdinando Wainman, who was in charge of artillery and horse troops, Captain William West, another high-ranking officer; and Captain Gabriel Archer, an early leader who fought for control of the settlement with John Smith, the man famous as the colonist saved by Pocahontas from execution by her native American people. (The event may have been over-dramatized in Smith’s writings, some historians believe.)

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

A combination of forensic examinations of the skeletons, items found on the bodies such as a captain’s ceremonial staff and stash, and archival records helped scientists identify each individual, according to Douglas Owsley, a physical anthropologist at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History who assisted in the analysis.

%20Overview%20of%20the%20chancel%20burial%20excavations_%20Archaeologists%20(from%20left%20to%20right)%20Mary%20Anna%20Richardson%2C%20Danny%20Schmidt%2C%20David%20Givens%2C%20Dan%20Smith%2C%20Don%20Warmke%2C%20Jamie%20May%2C%20Dan%20Gamble%2C%20and%20Dr_%20William%20Kelso_%20Photo%20by%20Mi.jpg?w=270)

Excavators uncover four graves at Jamestown. Photo courtesy Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation

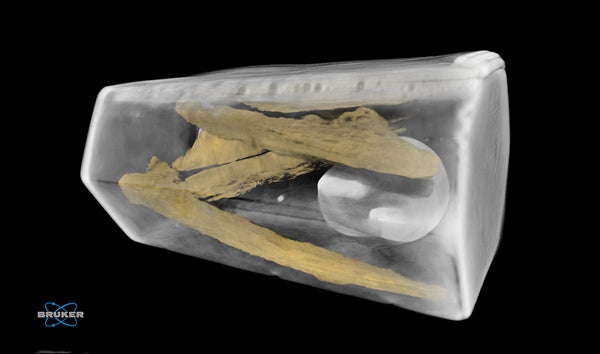

In Archer’s grave, on top of his coffin, excavators discovered a mysterious silver box, about 2.5 inches long and 1.5 inches wide and hexagonal in shape. “We couldn’t open it,” says William Kelso, director of archaeology at the Jamestown foundation. The lid was corroded shut and scientists feared damage if they forced it. So they turned to CT scans to probe the contents.

“What we saw were several good-sized fragments of bone, and a vial,” Kelso says. “This looks very much like a common item in Catholic burials at the time, called a reliquary. If this was found in a church in Europe, we’d think the bone chips came from a Catholic saint, and the vial would have been filled with holy water, or perhaps blood.”

What is surprising, Kelso says, is that Jamestown was emphatically not Catholic. Henry VIII had split with the Pope in the 1500s, and England had been vying with Catholic powers France and Spain ever since. The Spanish Armada tried and failed to invade England in 1588. King Phillip III of Spain, who saw himself as a great champion of the Pope, was intent on contesting England for colonial and religious supremacy in the New World. Fortifications at Jamestown were built to ward off Spanish attacks, Kelso says. And in 1607, a member of the colony’s governing council was executed for being a Catholic spy. “The great geopolitical struggle of the 16th century was the struggle between Protestant and Catholic countries,” Horn says.

Therefore, Horn continues, he would not be surprised to learn of a secret network of Catholics in Jamestown, perhaps plotting to take over the settlement. “King Phillip, at the time, had a vast network of spies in London and it would not have been impossible to insinuate one into the Jamestown expedition,” he says. It is not clear that Archer was actually one of them, however. The reliquary was placed on the coffin, not on the body, so it could have been put there after death by a Catholic sympathizer. “We have, over 22 years of excavations, found a large number of rosaries and wondered what they were doing there,” Kelso notes. “Secret Catholics could account for that.”

The other possibility, Horn says, is that the object “is an example of a messy transition between religions.” The Church of England was relatively new, and practitioners may have been fond of some old Catholic rituals and found new uses for them in their burgeoning church.

Either way, Kelso says, the discovery made him sit up sharply. “I always think the Protestant Reformation said ‘no graven images,’ so this really did surprise me,” he says. He would like to get into the box to do DNA analysis on the bones, hoping to shed some more light on early religion in the American colonies, a situation more than 400 years old but newly complex.