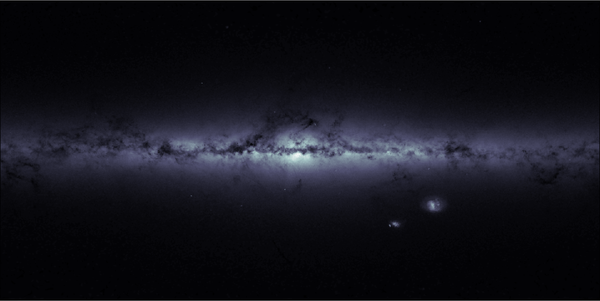

In an eagerly anticipated development, astronomers have created the largest and most precise 3-D map of the Milky Way galaxy. The European Space Agency's $1-billion Gaia mission released its newest data set in April, detailing the positions and motions of more than a billion stars.

The Gaia spacecraft, launched in 2013, scans the entire sky from its orbital parking spot above the side of Earth opposite the sun. Its unprecedented map is based on 25 separate observations of individual stars and their movements over about two years and contains a representative sample of 1 percent of the Milky Way's orbs. The data, described in a series of papers published online starting in April in Astronomy & Astrophysics, can be extrapolated to simulate the galaxy's past and future.

“We are measuring a map in a moment in time, but we can also go backward and forward,” says Jos de Bruijne, Gaia's deputy project scientist.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Gaia released its first data set in September 2016. But because of limited observation time and reliance on prior knowledge of celestial positions, it tracked the distances and motions of only two million stars. The second data set contains similar details on 1.3 billion of them—650 times as many as the initial trove.

The telescope can accurately observe stars in the galactic center, up to 30,000 light-years away—equivalent to a person on Earth spotting a penny on the moon. “The precision of the proper motions measured by Gaia is what really makes it so revolutionary,” says Allyson Sheffield, an astrophysicist at LaGuardia Community College, who was not involved in the project.

Gaia's two optical telescopes and three scientific instruments can also measure stellar brightness, temperature and composition. The new data set includes stars' colors, which can reveal crucial details about their surface temperature and age. Such diverse observations make the spacecraft a “one-stop galactic-structure shop” for astrophysicists, Sheffield says.

The data also include the radial velocities—the motions toward or away from Earth—of seven million stars. Such measurements allow scientists to calculate the speed of these orbs with respect to our sun, which in turn reveals more about how the galaxy may have evolved. As a bonus, the data set contains observations of 14,099 asteroids orbiting within the solar system.

Precise knowledge of stellar motions will not only improve scientists' understanding of galactic history and evolution, it could also offer clues to the nature and distribution of mysterious “dark matter” and could test alternative theories of gravity, says Amina Helmi, an astrophysicist at the Kapteyn Astronomical Institute in the Netherlands and a member of the ESA's Gaia mission.