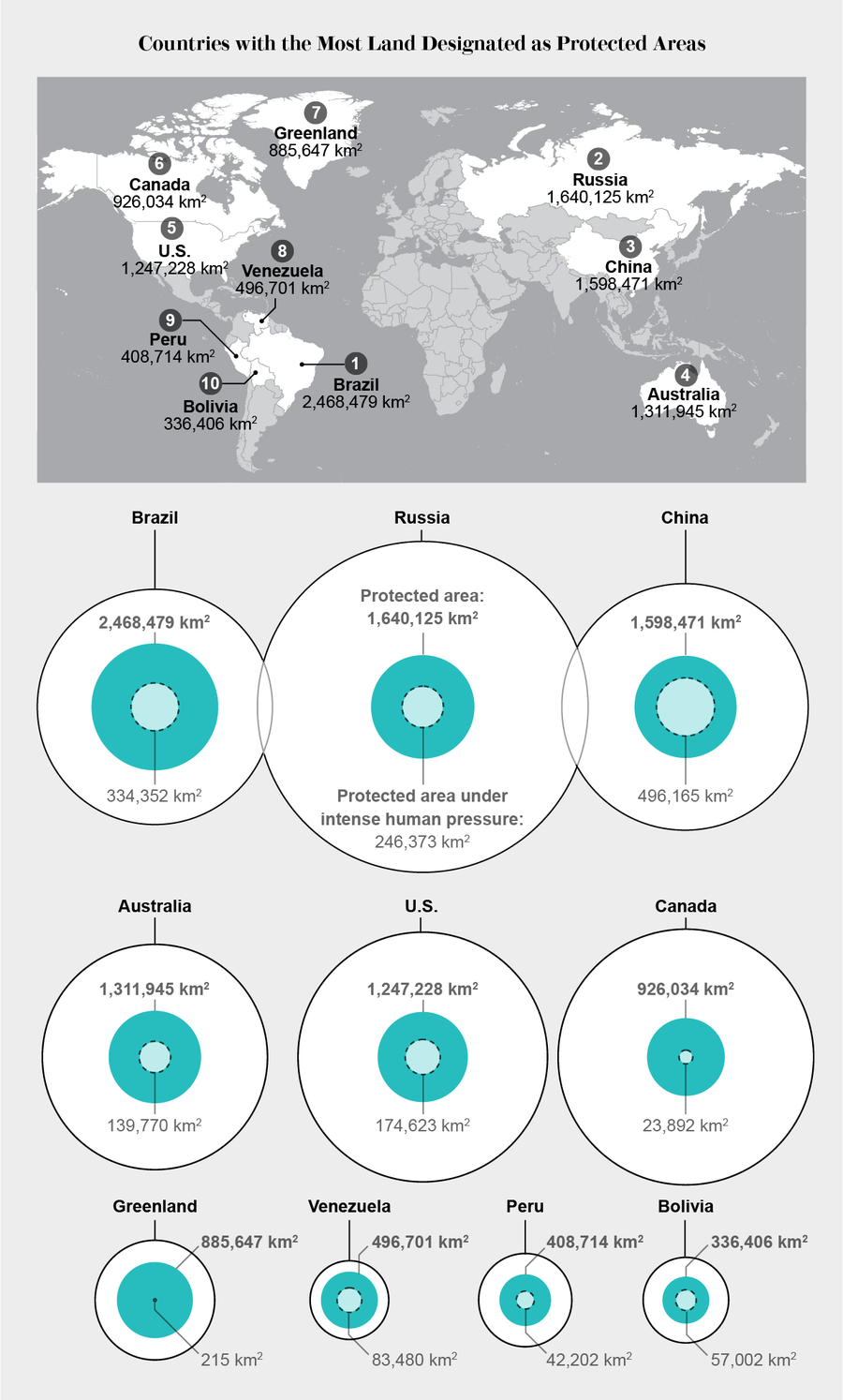

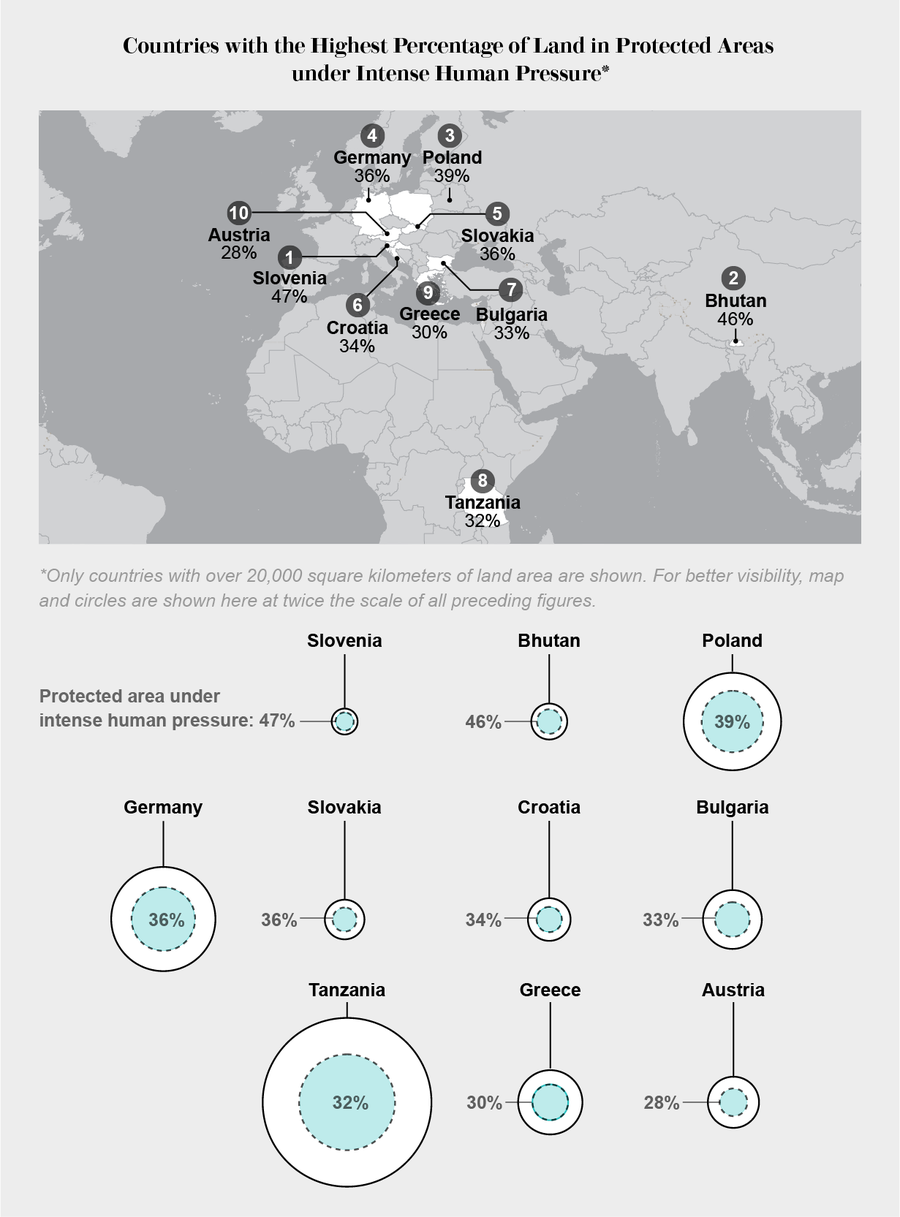

About one third of the world’s protected land faces intense pressure from human-related factors such as buildings, agriculture, roads and nighttime lighting, a new study from the Wildlife Conservation Society and the universities of Queensland in Australia and British Columbia in Canada shows. Intense human pressure is linked to the decline of biodiversity, the feature that protected areas are meant to preserve.

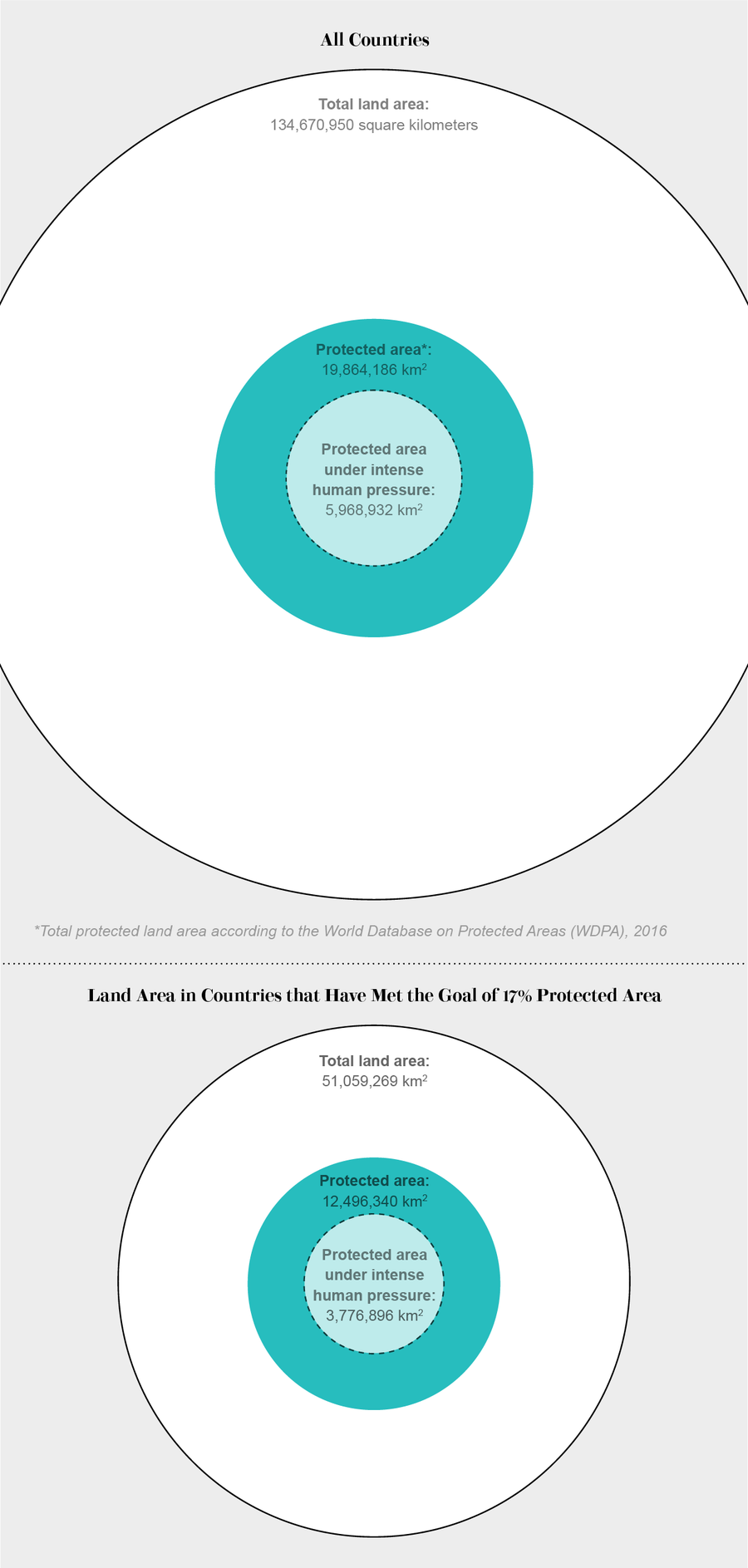

The 1993 Convention on Biological Diversity, signed by 168 countries, has mandated 17 percent of land be contained in “effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected” protected areas by 2020. Designated protected areas across participating countries currently account for about 14.7 percent of land globally. But when areas facing intense human pressure are subtracted, the protected area percentage drops to 10.3. Of the 111 countries that have individually met the 17 percent mandate, only 37 would still meet that threshold if areas under heavy pressure were removed.

The study’s findings, published in the May 18 issue of Science, show, despite apparent global efforts, many protected areas may not be effectively guarding against biodiversity loss. The graphic below highlights some of the data associated with the study, including values for specific outlying countries.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Source: “One Third of Global Protected Land Is under Intense Human Pressure,” by Kendall R. Jones et al., in Science, Vol. 360, No. 6390; May 18, 2018. Credit: Amanda Montañez