Since North Korea’s foreign minister recently floated the idea that his country might test a hydrogen bomb in the Pacific Ocean, the North’s leader Kim Jong-un and U.S. Pres. Donald Trump have engaged in an escalating battle of name-calling and threats. As unsettling as the exchange has been, fortunately there has so far been no demonstration of thermonuclear weaponry. Many experts question whether Pyongyang actually has an H-bomb and the capability to accurately deliver it. But it is difficult to fully dismiss its sudden decision to ratchet up its rhetoric from nuclear to thermonuclear—and its suggestion that it would move its tests from underground bunkers to the open ocean.

North Korea’s six nuclear tests over the past decade have steadily grown more powerful. Whether it could build an H-bomb in the near future and would test it in the atmosphere—such tests were prohibited by the international 1963 Limited Test Ban Treaty—is an open question. The environmental and health impacts this kind of test are also unpredictable and would largely depend on how the bomb is built, where it is detonated and how the weather patterns at that time affect the radioactive fallout.

But the U.S. is well-versed in those uncertainties, having presided over history’s most catastrophic nuclear weapons test to date. The March 1954 Castle Bravo H-bomb test has been studied extensively over the past six decades, and its lessons provide some clues about the potential impact and lingering effects of such a detonation if North Korea were to test an H-bomb somewhere in the Pacific.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

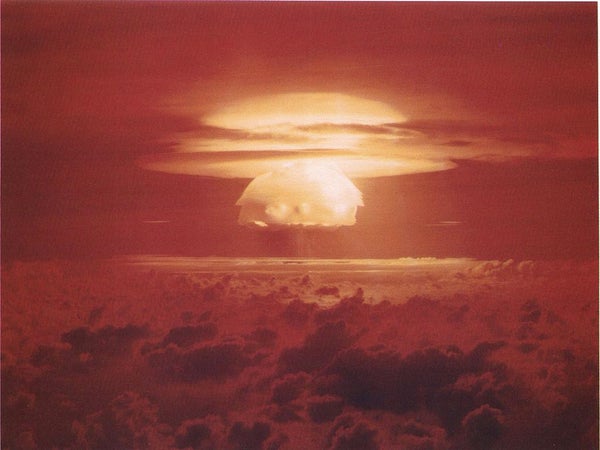

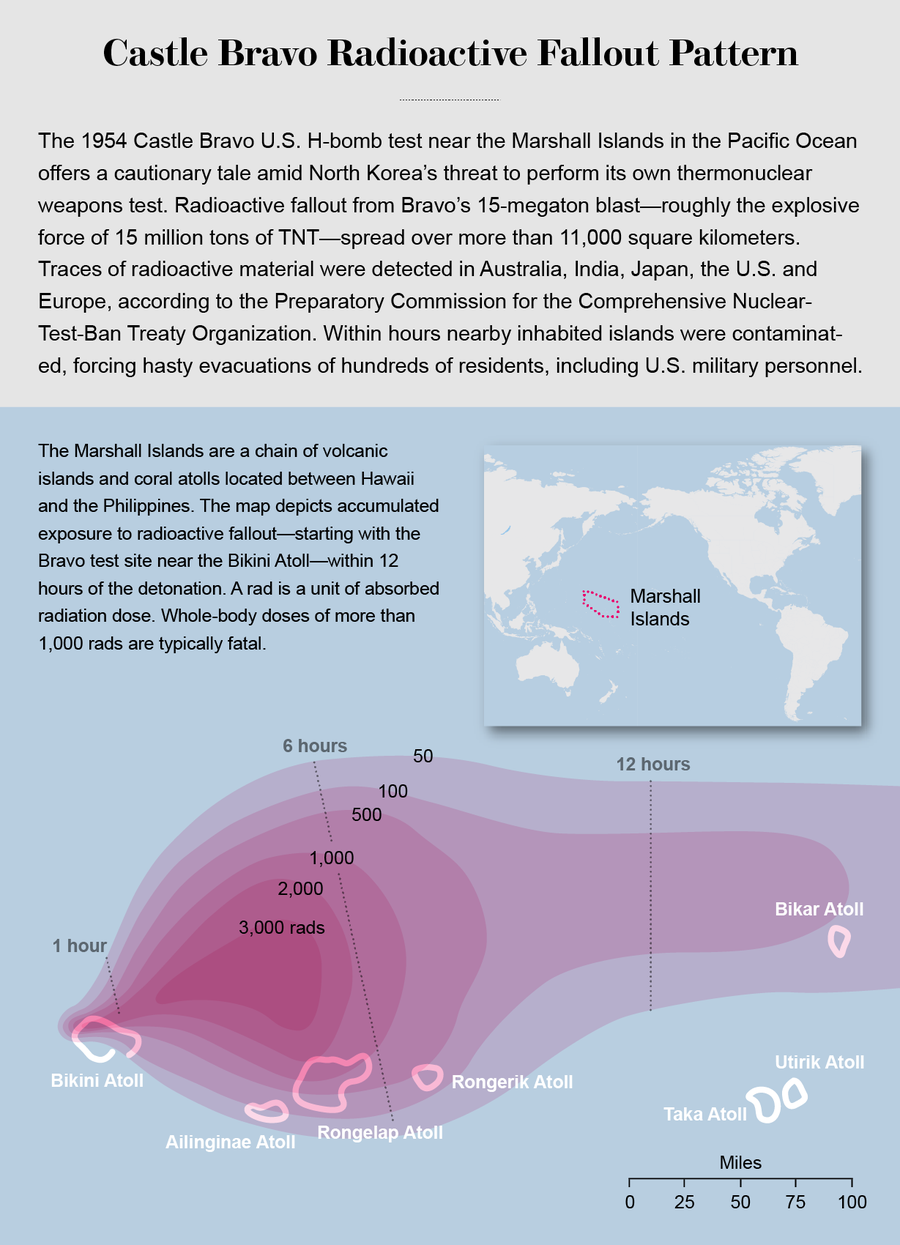

The Castle Bravo bomb—code-named “Shrimp”—remains the most powerful nuclear weapon ever tested by the U.S., about 1,000 times stronger than the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II. Shrimp’s detonation unleashed a 15-megaton blast that was two-and-a-half times greater than expected. (A megaton has the explosive force of one million tons of TNT.) It also resulted in the largest nuclear contamination accident in U.S. history, as shifting winds carried radioactive fallout across the inhabited atolls of Rongelap, Ailinginae and Utirik as well as Rongerik—where U.S. servicemen were stationed—in the central Pacific’s Marshall Islands.

To set off an H-bomb, a nuclear fission blast is used as a detonator. It produces radiation that generates the high pressures and temperatures needed to create secondary fusion reactions from the bomb’s hydrogen fuel—the process behind an H-bomb’s horrific destructive force. The yield of Castle Bravo’s Shrimp was much larger than expected because its designers at Los Alamos National Laboratory underestimated how much of the bomb’s fuel would become reactive during the fusion process. This was apparently because they did not fully understand the physics involved, says Edwin Lyman, a senior scientist in the Union of Concerned Scientists’ Global Security Program. Even today, “North Korea or some other immature nuclear weapons state may not even be able to accurately predict the yield that [they’re] going to get, which is a little scary,” Lyman adds.

The location of any North Korean H-bomb test may be even more important than the weapon itself, says Patrick Cronin, senior director of the Asia–Pacific Security Program at the Center for a New American Security think tank in Washington, D.C.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Sources: Defense Technical Information Center, Defense Threat Reduction Agency

“Where would Kim plan to test an ICBM [carrying an H-bomb]? The oceans may be large, but they are also littered with thousands of bits of land and many more thousands of boats and ships,” Cronin notes. The Castle Bravo blast contaminated the Japanese fishing vessel Lucky Dragon No.5, with its 23 crewmen exposed to about 260 rads—a measurement of radiation absorbed by human tissue. Although not fatal, such a dose is enough to cause cell-damaging acute radiation syndrome. Doses of 200 to 1,000 rads delivered in a few hours can cause serious illness, and a dose of more than 1,000 rads to the entire body at once would likely be fatal.

The impact on the ocean life below depends on the altitude at which the bomb explodes, Lyman says. The U.S. conducted a total of 67 nuclear tests (pdf)—some above the water and some beneath—in the Marshall Islands between 1946 and 1958, when the country halted atmospheric tests (largely due to Castle Bravo). “The shallow underwater tests performed during that time did create a highly radioactive plume with some fission products trapped in the water, although that material disperses and gets diluted fairly quickly,” Lyman says. “The bigger threat to marine life is likely from the initial blast and the initial radiation, but the dispersion patterns are complex and hard to predict.”

Residual radioactive particles propelled into the air—known as fallout—create a longer-term threat to living things near a nuclear blast. The size and weight of those particles, combined with size of the blast’s mushroom cloud and wind shear, determines how widely the fallout is dispersed. Castle Bravo’s cloud reached an altitude of 30 kilometers in just two minutes. Fanned by winds that shifted suddenly to the east, the fallout plume spread high levels of radioactivity over an area that stretched for hundreds of kilometers and included several inhabited islands.

Even though there is still no proof North Korea has a hydrogen bomb, “it’s not surprising that we’re talking about it,” Lyman says. “They’ve been putting significant resources into their weapons development for decades.” Pyongyang’s latest known nuclear test, on September 3, is estimated to have been a 160-kiloton detonation—far below an H-bomb’s capabilities yet much greater than the 10-kiloton bomb the country tested just a year ago. (A kiloton has the explosive force of 1,000 tons of TNT.)

Even if North Korea plans a test designed to minimize its impact on the environment, “they could screw up,” Lyman notes. “The uncertainties inherent in an immature nuclear weapons program, as exemplified by the U.S. experience with Castle Bravo, drive this risk to an unacceptable level.”