This year began with terrifyingly massive blazes that tore across eastern Australia, and it will end with a photo-finish race to see if 2020 will beat 2016 as Earth’s hottest year on record.

Though the coronavirus pandemic has been a defining story of 2020, the year has been a notable one on the climate front as well. Developments have ranged from an agonizing array of warming-fueled disasters that impacted the lives and livelihoods of millions around the world, to signs that some countries (including China and members of the European Union) are making efforts to move forward on reducing the greenhouse gas emissions that are driving this warming.

Here is a roundup of five of the biggest climate stories of the year:

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Raging Wildfires

The flames of record-breaking conflagrations tore through the parched parts of Australia, the lush Amazon and huge swaths of the Western U.S. this year. In Australia, fires early in the year affected hundreds of millions of wild animals and spewed smoke 20 miles up into the atmosphere. In California, a relentless onslaught of blazes torched more than four million acres—almost doubling the state’s previous record for the most area burned in a season. The August Complex fire alone scorched more than one million acres, making it by far the largest in California’s recorded history. Millions in the West felt the fires’ impacts as smoke spread, making the air unhealthy to breathe. The Amazon also saw terrible destruction from blazes, including in virgin forest.

Rising temperatures can contribute to devastating fire seasons because they increase the odds of having major heat waves that dry fuels out. This makes for bigger and more intense fires. Warming can also exacerbate droughts. A study submitted in March found that for Australia, extreme fires like the ones seen this year are now 30 percent more likely because of climate change. These massive blazes also pump greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, worsening the warming—so actual fires are adding fuel to the proverbial one.

Flurry of Hurricanes

Damaged houses are surrounded by mud and debris in the municipality of Villanueva near San Pedro Sula, Honduras, after the Chamelecón River overflowed because of heavy rains caused by Hurricane Iota on November 20, 2020.

Credit: Wendell Escoto Getty Images

Once the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season got going, it did not seem to want to stop. From the May arrival of Tropical Storm Arthur (before the official June 1 start of the season) through Hurricane Iota in November, the year saw a record 30 named storms—the most of any single season. For only the second time ever, forecasters used up the official hurricane name list and had to move on to the supplemental Greek alphabet. In addition to the sheer number of storms, 27 of those that formed this year were the earliest of their storm sequence to do so. As ocean waters continue to warm—and reach temperatures that can support hurricanes earlier in the year—it is possible those records could be broken in the future.

Chart-Topping Heat?

Neighborhood of Los Angeles ahead of a heat wave during the 2020 Labor Day weekend.

Credit: Frederic J. Brown Getty Images

The year is not over yet, so it is still uncertain where it will rank in the pantheon of annual global temperatures. But it will definitely vie for the top spot. As of November’s end, 2020 was only 0.02 degree Fahrenheit behind 2016 at the same point, according to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration data that go back 141 years. And that is without the major El Niño event that boosted global temperatures four years ago. The fact that 2020 will at least come close to 2016 is evidence of the long-term warming trend driven by fossil fuel burning and other human activities that emit heat-trapping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. If this year does take the number-one spot, the pace at which new annual heat records are being set means it may not keep it for very long.

COVID-Driven CO2 Drop

Adolfo Suárez Madrid-Barajas Airport in Spain, seen empty and deserted during the COVID pandemic.

Credit: Adrián Baúlde Getty Images

As flights were grounded and car commutes were cut by more people staying home amid the pandemic this year, global greenhouse gas emissions dropped by about 7 percent—an unprecedented amount. That drop is not a silver lining, though, because it underscores the extent to which humanity now has to go to reach the goals of limiting warming and preventing its worst effects. Future annual reductions need to be on par with this year’s but must be sustained and not nearly as disruptive, experts say. That means instead of relying on the largely individual actions that drove much of this year’s change, extensive and concerted government policy initiatives are needed, as well as investment in clean energy and transportation.

U.S. Reversal

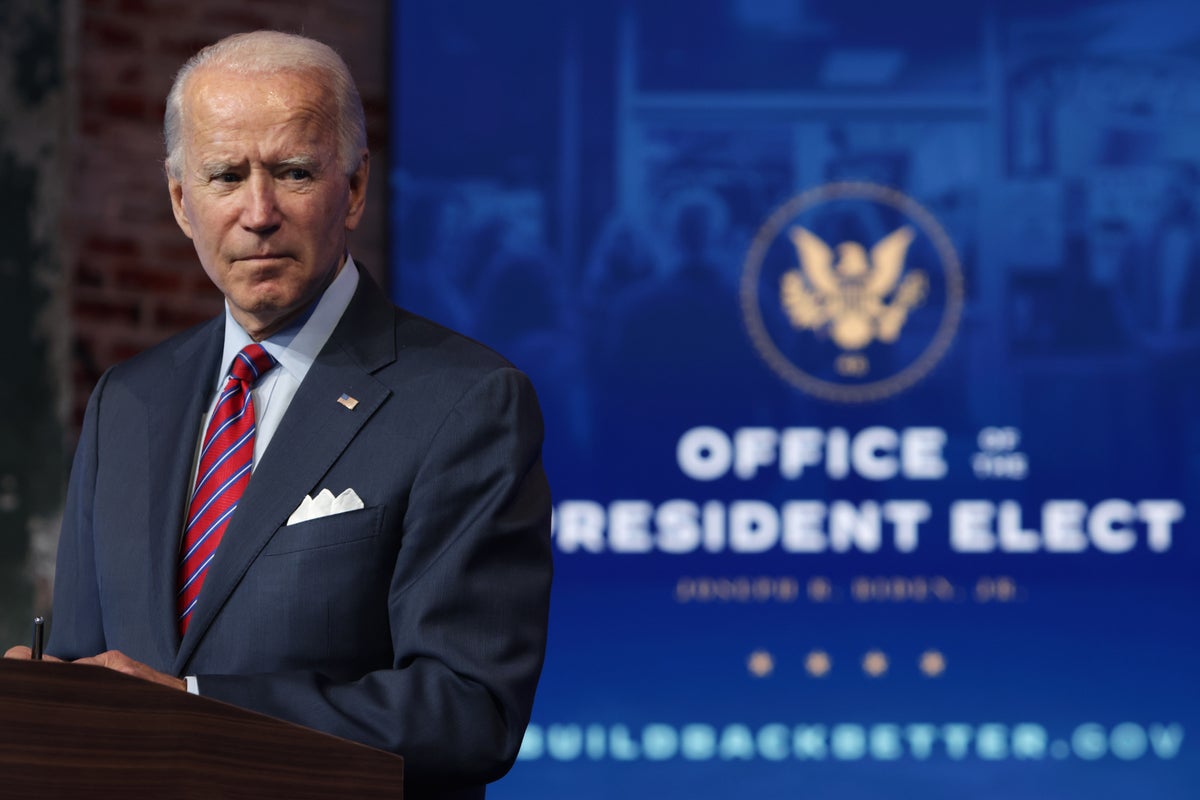

President-elect Joe Biden speaks at the Queen theater in Wilmington, Del., on December 4, 2020.

Credit: Alex Wong Getty Images

In terms of tackling climate change, the biggest story of the year was probably the impending reversal in the U.S.’s position with the election of Joe Biden as president. Although this flip will not happen until after Biden is inaugurated on January 20 next year, his positions on climate change are already sending a clear signal to businesses, state governments and other countries about where the federal government will stand on the issue during his tenure. The administration of Donald Trump rolled back numerous environmental regulations, including several that are key to reining in greenhouse gas emissions. These include reducing requirements to ramp up fuel efficiency in cars and relaxing requirements for the oil and gas industry to monitor for leaks of methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Biden has pledged to undo these rollbacks, but this will take time in many cases. New rules will have to be shaped through the required federal bureaucratic channels. One of the first changes Biden has said he will make is to reverse another major climate move Trump took this year: pulling the U.S. out of the landmark 2015 Paris Agreement to limit global warming. Biden has pledged to start the process to reenter the accord on his first day in office, and this has been seen as a sign to the rest of the world that the U.S. wants to be a major player in international efforts to tackle climate change once again.