Pharmaceutical giant Biogen now admits that it made a mistake back in March when it stopped a pair of trials of an experimental Alzheimer’s drug. A deep analysis of the data, released Thursday, suggests the drug, called aducanumab, did make a difference for patients who took the highest dose for the longest period of time—but only in one of two studies.

Earlier results were muddied by the discontinuation of both studies after initial data suggested the drug failed to offer significant benefit and by unintended differences between the trials, which were meant to be identical. In a news conference on Thursday,Biogen vice president Samantha Budd Haeberlein explained that more patients in the successful trial took the highest dose of the drug for longer.

Some Alzheimer’s experts accept Biogen’s explanation and say they hope the U.S. Food and Drug Administration will soon approve the drug. Sharon Cohen, medical director of the Toronto Memory Program and an investigator in the aducanumab trials,said at Thursday’s news conference—which was held at the annual Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease meeting in San Diego—that she found the results “exhilarating.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“Those of us who know this disease well, know what it means to lose yourself slice by slice. And anything you can hang on to is a triumph,” Cohen said, citing a statistic from the new data suggesting that scores gauging disease progression for trial participants at the highest doses declined 40 percent more slowly than for those taking a placebo. “You have to think about this disease as a long, slow disease. And if you can slow it, you are winning out.”

But others, while happy to see more data, are less convinced. “It’s not a cure, and it’s not really a treatment that’s going to make a noticeable difference to someone’s [disease] course,” says Robert Howard, a professor of old-age psychiatry at University College London. “If it’s real, it’s a really important proof of concept. But this isn’t a clinically useful treatment yet, based on the data.”

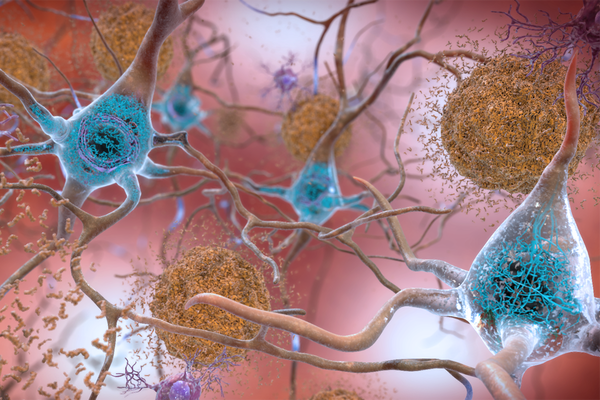

A lot had been riding on trials of aducanumab, and the on-again, off-again results have upended the research world. If the drug truly works, that finding would support the so-called amyloid hypothesis, which argues that effective Alzheimer’s treatment depends on reducing the buildup of a protein called beta-amyloid in the brain.

Other drugs aimed at beta-amyloid have failed to show a benefit, and when Biogen shelved the aducanumab studies in the spring, some took the decision as proof that the amyloid hypothesis—which has dominated the Alzheimer’s research world for decades—had failed. The company’s resurrection of aducanumab has breathed new life into that line of research.

Biogen announced in October that it was reassessing its March finding and would be applying to the FDA for approval to market aducanumab to patients with early-stage Alzheimer’s. There has not been a drug approved to treat the disease since 2003, and aducanumab would be the first aimed at modifying its progression rather than just its symptoms.

Thursday’s conference included Cohen and several other high-profile Alzheimer’s researchers and physicians who treated patients in the trials. They said they agreed with Biogen’s analysis of the data and that their patients had seen good results with the drug and were eager to start taking it again. Biogen is planning a follow-up study to allow anyone in previous aducanumab trials access to the medication.

In explaining why the results of one of the two trials, called EMERGE, were more positive at the conference, Budd Haeberlein said that 29 percent of patients in EMERGE and 22 percent of patients in the other trial, ENGAGE, received the full regimen of 14 doses of 10 milligrams per kilogram of weight. Both trials started in the late summer of 2015, and patients were followed for 18 months.

To make its March decision to discontinue the studies, Biogen had combined EMERGE and ENGAGE data and cut off results as of December 2018—meaning fewer people had completed the full-dose regimen of aducanumab, and the positive results were diluted, Budd Haeberlein said.

Patients both with and without a gene called APOE4, which dramatically increases the risk of Alzheimer’s, saw improvements in the EMERGE data. Those with APOE4 had more side effects from the drug, but they were manageable, Budd Haeberlein and the expert panel said.

Eric Reiman, executive director of the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute, a research organization, notes that while findings from the trials are not definitive, they seem reasonably likely to reflect a clinical benefit. “If confirmed, these findings would be a milestone in the fight against Alzheimer’s disease,” says Reiman, who is a leader of the Alzheimer’s Prevention Initiative, an organization aimed at accelerating the evaluation and approval of therapies to prevent Alzheimer’s.

Howard, who recently co-authored a paper in Nature Reviews Neurology raising concerns about the aducanumab research, says he is not convinced by Biogen’s explanation that the disparate results can be explained by the small difference in outcome in those who received the highest dose. His reasoning is: Why should we believe the one trial that showed benefit instead of the one that showed none?

Howard is also troubled by the observation that those on the highest dose suffered the most side effects. People who have significant side effects are more likely to be taking an active drug versus a placebo, so they can “unblind” a study. Once doctors know which patients are on the active drug, they may unconsciously skew results in its favor, he says. And the highest-dose group had a higher dropout rate, which can tilt results toward those who see a benefit from a drug, Howard says, because the smaller remaining high-dose group is more likely to include them.

Discarding the fact that one study showed no benefit and the possibility that the results of the other were biased, “I wouldn’t be convinced to offer this treatment to my patients on the basis of tiny benefits and the clear side effects and risk and expense and inconvenience of having the treatment,” Howard says.

If the FDA gives aducanumab fast-track approval, it would likely monitor the drug over time to confirm whether it is both safe and effective. More definitive data on aducanumab and findings from other plaque-reducing approaches will become available in the next few years, Reiman says.

Researchers also are studying other types of treatments, including targeting infections and inflammation, and any successful therapy will likely involve a combination approach, based on multiple drugs, according to Heather Snyder, vice president of the Alzheimer’s Association, a research and advocacy group.

Reiman says he is excited about the relationships between aducanumab’s biological effects and the suggested clinical benefit. With additional work, he believes there is a chance to use biological tests to find and support the accelerated approval of effective prevention therapies. “The encouraging aducanumab findings,” he says, “could have a profound effect on the effort to find other drugs to treat and prevent this terrible disease.”