Editor’s Note (10/15/19): The study this story was based on has been retracted because of technical errors in how a particular mutation was identified in a genetic database, which made the central finding invalid.

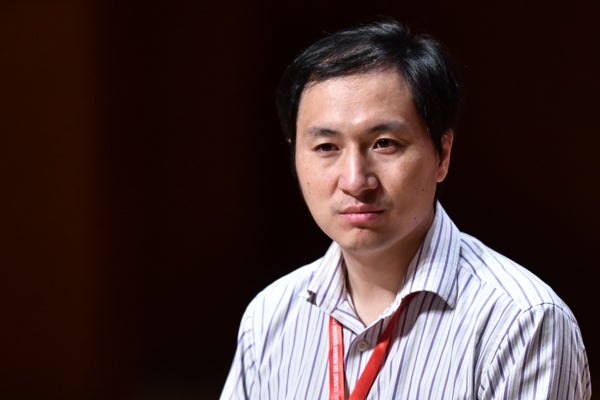

When Chinese scientist He Jiankui edited the genes of twin baby girls last year, he said he was doing it to protect them against HIV infection; their father was HIV-positive. The now-disgraced scientist has said he did not want the girls to get the virus, which causes AIDS, because of a severe stigma against it in China.

But a new study suggests that he may have subjected them to a danger separate from the risk of catching HIV. The intended gene mutation appears to shorten people’s lives by nearly two years, according to a study published Monday in Nature Medicine.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“JK was foolish in choosing this gene to mutate, because he may have compromised lifespan in the two girls,” says British stem cell scientist Robin Lovell-Badge of the Francis Crick Institute, referring to He by his nickname. Lovell-Badge was not involved in the new study.

The so-called delta-32 mutation appears to make people resistant to HIV when it occurs on both copies of the CCR5 gene—one inherited from each parent; while one copy of the mutation provides somewhat weaker protection.

Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley looked for this common CCR5-delta-32 mutation in a database of more than 400,000 middle-aged and older volunteers in the United Kingdom. In the database, people who naturally had two copies of the mutated gene were found to be 20 percent more likely to die by age 76 than those with either one copy or none. In addition, there were fewer volunteers with the double mutation than would be expected by its prevalence in the general British population, suggesting that the missing people had died or were not healthy enough to volunteer, says the study’s lead author, April Wei. People with only one copy of the mutation lived just as long as those with no copies.

Scientists cannot yet explain the connection between the gene mutation and a shortened lifespan, says Wei, an evolutionary geneticist and postdoctoral student at Berkeley. But it may be because the mutation also seems to be associated with an increased vulnerability to viruses like the flu and West Nile.

He’s experiment marked the first time that a human embryo had been gene-edited and then allowed to develop until birth. Gene-edited cells in an adult are not passed down to future generations (unless they are reproductive cells), and medical treatments that target these genes are considered preliminary but promising. Edits to an embryo change the genetic code of most of its cells and are passed down to future generations. Some people consider all edits to an embryo immoral, while others, including Lovell-Badge, can see some benefit to gene edits that prevent an otherwise unavoidable disease. But many say the science is too premature for human use.

The global scientific community reacted with outrage to news of He’s gene edits. Scientists nearly universally condemned the fact that he had edited embryonic genes, as well as the choice of gene and the process he used to inform the families of what he was doing. The World Health Organization, several national academies, and scientific groups have since called for (or considered) a global moratorium on gene editing.

He has been fired from his position at the Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, and has disappeared from public view, though he did dispute claims earlier this year that he had been arrested. In the saga’s latest installment, a Stanford bioethicist told STATlast week that he advised the Chinese scientist not to respond to requests from a fertility clinic in Dubai, among others, who wanted to learn his gene-editing techniques.

At issue now is whether human embryo gene editing should be regulated by governments. Harvard Medical School Dean George Q. Daley has come down against regulation. It too often limits legitimate science, says Daley, a stem cell scientist who has faced stifling government regulation in his own field. But Daley says the new study is a reminder that scientists’ understanding of genetics remains limited. “It’s a lesson in humility, I think, more than anything,” Daley says. “What this study also is concrete evidence of is the ignorance that we have.”

The CCR5 gene has been well studied in connection with its apparent protection against HIV, but not much in other contexts, says Lovell-Badge. The double mutation has also been associated with improvements in mental ability in mice and recovery from stroke in humans. The gene is known to be active in the central nervous system, including the brain, so it may have some neurological effect that is as-yet not understood, Lovell-Badge says. “We really don’t understand what it’s doing,” he says. “Its role is in the immune system is not entirely clear, and we really don’t understand what it’s doing in the brain.”

A single copy of the mutation probably offers some benefit, Lovell-Badge says, or it would not be as common as it is among people of northern European ancestry. But if it has a negative effect only after someone is too old to reproduce, evolution would not limit its frequency. Such an effect would only just be noticeable when looking at huge numbers of people, as in this study, Lovell-Badge says.

People from Africa and Asia are far less likely to have the delta-32 mutation, which also raises questions about it will affect the Chinese girls and another embryo whose genes He edited but whose birth has not yet been publicly announced.

It is also unclear whether He succeeded in mutating both copies of the gene in one of the girls; the editing was not successful in the second girl, and it is not clear what will happen with the third edited embryo.

Lovell-Badge says editing embryos may have a place in science, but with our current understanding of genetics, it should only be used to prevent actual diseases that will unavoidably result from the child’s birth, such as cystic fibrosis or sickle cell disease.

“I would do something for which there’s going to be an obvious clinical benefit from altering a gene,”he says. “Generally, that should be correcting a gene defect back to a normal variant—rather than what [He] was doing, [attempting to enhance] the babies to make them resistant to HIV, when in fact, he’s done who-knows-what damage.”