When NASA’s latest Mars-roving robot, Perseverance, landed on the Red Planet in February, its cargo included a long virtual list of “firsts.” Perseverance was the first ever spacecraft to perform an entirely autonomous ultraprecise landing on another planet. In coming months it will also be the first to attempt to produce pure oxygen from the world’s thin carbon-dioxide atmosphere via its experimental MOXIE instrument. And before the conclusion of Perseverance’s mission, it will be the first to gather Martian samples for eventual return to Earth, potentially also making it the first mission to uncover signs of life beyond Earth. But the rover’s most spectacular first may occur next week, when it is expected to deploy a small, four-pound parcel from its underbelly.

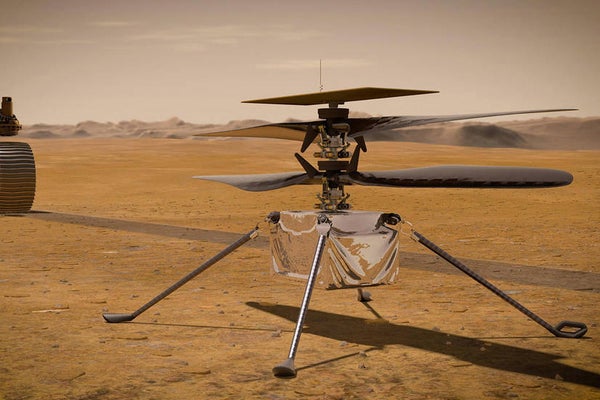

That parcel is a solar-powered helicopter, called Ingenuity, that will attempt to take flight on Mars as early as April 8. If successful, it could serve as a modest airborne scout for Perseverance’s ongoing peregrinations and, in the process, become the first powered aircraft to ever operate on another planet and pave the way for future interplanetary missions to fly the not-so-friendly skies of worlds beyond.

“We’ve done everything we can here on Earth,” says Taryn Bailey, an Ingenuity mechanical engineer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). “We’ve simulated the Mars environment. We’ve done extensive testing. We’ve studied for the exam as much as we can. Now we have to take it.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

But while Ingenuity may portend the future of space exploration, the tiny helicopter also honors the past. Tucked beneath Ingenuity’s solar panel—wrapped around a cable and secured with insulative tape—is a small swatch of timeworn textile. Nearly 118 years ago, this unbleached “Pride of the West” muslin fabric—purchased at the Rike-Kumler department store in downtown Dayton, Ohio—was part of the 1903 Wright Flyer, the world’s first airplane.

First in Flight

Near the turn of the 20th century, at a time when heavier-than-air flight was deemed impossible—even crazy—two autodidactic brothers named Wilbur and Orville Wright invented the airplane in the back of their bicycle shop in West Dayton.

“Wilbur began by writing to the Smithsonian Institution, asking for any information they had on flying,” says Stephen Wright, the Wright brothers’ great-grandnephew. Over the next several years, the brothers built experimental gliders and manufactured a wind tunnel to conduct lift and drag tests. “With the wind tunnel,” Stephen Wright says, “they were able to gather precise data on tiny airfoil designs, scraps of sheet metal they had lying around their bicycle shop.”

But propeller design was arguably the brothers’ hardest task. “They concluded that an air propeller was really just a rotating wing,” recalled their mechanic Charlie Taylor, who built the custom engine for the Wright Flyer, “and by experimenting in the wind box they arrived at the design they wanted.” Taylor’s story appeared in an article he wrote in the December 25, 1948, edition of Collier’s magazine.

To make their flying machine more aerodynamic, Wilbur and Orville Wright stitched unbleached Pride of the West muslin fabric with a Singer sewing machine and stretched it across the aircraft’s wings, rudder and elevator. On December 17, 1903, after some four years of victories, setbacks and painstaking preparations, the Wright brothers finally made the world’s first powered, controlled heavier-than-air flight on the windswept beaches of North Carolina’s Outer Banks, near the town of Kitty Hawk.

From Kitty Hawk to Mars

More than a century later, Ingenuity’s team members see obvious parallels between their pioneering mission and that fateful first flight.

“The Wright brothers put most of their energy in the test program,” says Bob Balaram, Ingenuity’s chief engineer at JPL. “Like building the airplane, the Ingenuity test program was as much, if not more, challenging than the building of the helicopter itself. Like the Wrights, we had to build our own wind tunnel, only we used over 900 computer fans. Matt Keennon, he’s our Charlie Taylor—the mechanic who built the Wright Flyer engine. Matt hand wound the copper for each motor. Each winding took about 100 hours under a microscope.”

But also like the Wright brothers, before the Ingenuity team began building components, it had to determine if flight was possible, especially on Mars, where the atmosphere is 99 percent less dense than the air on Earth. “Initially the test helicopter was manually driven,” Bailey says, “but human reaction time is inadequate for such a thin environment. That’s when we started looking toward an autonomous vehicle, a helicopter driven by a computer and commands.”

Two engineering models successfully endured extensive aerodynamic and environmental testing, helping the Ingenuity team determine it could, indeed, construct an autonomous system that could not only navigate the tenuous Martian air but also survive on the planet’s cold, radiation-bathed surface. “From there, we built the flight model, which also underwent extensive testing,” Bailey says. “And that helped bring us to where we are now.”

The Wright Stuff

Before Ingenuity left for Mars, JPL officials contacted Carillon Historical Park in Dayton, home of the Wright Brothers National Museum, to obtain an original Wright Flyer fabric swatch. “Back in the 1940s, Orville Wright had a number of these swatches made,” says Steve Lucht, curator of Carillon Historical Park.

But this is not the first time the Wright Flyer has hitched a ride into space. In July 1969 the late Neil Armstrong carried a piece of the plane to the moon during the Apollo 11 mission. And in 1998 the late John Glenn, then a U.S. senator and former NASA astronaut, flew on the space shuttle Discovery with a Wright Flyer fabric swatch in tow. Discovery also sent another swatch aloft in 2000 for a weeklong stay on the International Space Station as part of the STS-92 mission.

“This is another one of those times where I wish I could speak with my great-granduncles,” says Amanda Wright Lane, the Wright brothers’ great-grandniece. “Wouldn’t they be stunned, so pleased. It’s remarkable to think of where we’ve come in 118 years—to Mars, literally, to Mars.”

Orville Wright died on January 30, 1948, almost a decade before the dawn of the space age, although he lived to see the late pilot Chuck Yeager break the sound barrier. “We’re opening up a whole new dimension,” Bailey says. “Anyone who follows will be benefited. Sometimes you do things just to prove you can do them. We’re showing we can do this. I think that’s enough to propel us further.”