Oil and gas wells let loose a lot of methane, a potent greenhouse gas. In April, when the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency suspended for three months an Obama administration rule to restrict such emissions, it did not defend wells or deny climate change. Instead the agency said the rule had not been studied enough. For instance, the EPA said the costs to get new well-venting systems approved had not been analyzed, so oil and gas companies had been unable to provide input as required by law.

Earlier this month an Appeals Court disagreed and overturned the delay as an illegal and “capricious” maneuver. “Even a brief scan of the record demonstrates the inaccuracy of EPA’s statements,” a panel of judges from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit found. “The administrative record thus makes clear that industry groups had ample opportunity to comment…and indeed, that in several instances the agency incorporated those comments directly into the final rule,” the judges wrote. EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt was free to revise the methane rule, the court said, but it was already in place with the force of law, so he could not simply put it on ice.

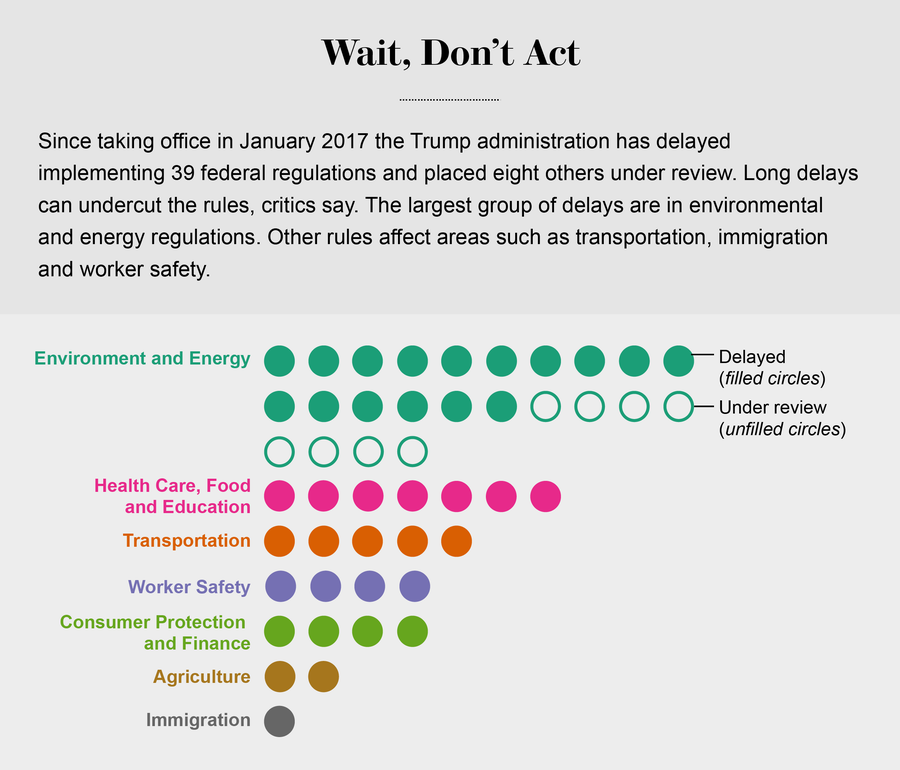

The delay tactic has become a hallmark of Pres. Donald Trump’s approach to environmental rules and other regulations, but the court decision pokes a hole in it. According to an analysis by Scientific American and legal scholars, federal agencies have suspended enforcement of at least 39 rules from the administration of Pres. Barack Obama affecting issues ranging from air pollution to airlines’ handling of wheelchairs. Other major environmental rules have been placed under review with an eye toward weakening them.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Some of the delays are indefinite, pending the outcome of the reviews or court cases. Most last from a few months to a few years. The suspensions have often come at the request of affected industries. Although a new presidency always revisits its predecessor’s regulations, “what’s unique about the Trump administration is that we’re seeing so much sloppy work, in the sense of these stays that have absolutely no justification,” says Emily Hammond, a professor at The George Washington University Law School who is tracking the issue. “We’re seeing stays that aren’t sufficient to withstand judicial review.”

Environmental groups are jumping to take advantage of the weakness. On July 12 a coalition filed suit against the EPA for its recently announced delay in the implementation of new public health–based standards for ozone pollution, on grounds similar to the methane challenge. Another coalition of environmental groups has sued the U.S. Bureau of Land Management to reverse a two-year delay of another methane rule, this one governing emissions from drilling on federal and Indian lands.

Agency officials say they are, in fact, acting legally. “EPA follows the law when ensuring the agency’s actions are consistent with our core mission and statutory authority granted by Congress,” agency spokesperson Amy Graham wrote in an e-mailed statement. “Where regulations may be unjustified or overly burdensome, we will consider all legally available means to provide regulatory certainty.”

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: Research by Rena Steinzor and Elise Desiderio, University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law; additional research by John McQuaid

In its first six months the Trump administration has suspended or placed under review a total of 47 Obama-era rules, according to a listof Federal Register filings compiled by Rena Steinzor, a professor at the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law, and law student Elise Desiderio, with additional research by this publication. The EPA is leading the charge, delaying and/or reviewing at least 14 rules, accounting for 30 percent of all cases across the government. The delays are part of an aggressive deregulatory agenda pushed by the White House and Republican-controlled Congress. Upon taking office Trump signed executive orders mandating a regulatory freeze and requiring agencies to repeal two existing rules for every new one it puts in place.

Under the Administrative Procedure Act, which governs most federal regulations, agencies must follow specific procedures for changing a rule, including postponing its effective date. The process takes a minimum of 60 days and the agency must spell out its reasoning. (Congress has the extra ability to wipe out rules within two months of their effective date with majority votes in the House and Senate; the current legislature used this procedure to repeal 14 last-minute Obama rules.) “Any agency’s proposed rulemaking must have a rational basis behind it,” says Robert Routh, an attorney for the Clean Air Council, a Philadelphia environmental organization among those challenging the methane rule suspension. “You open up public comments, receive comments and evidence, then you have to justify the decision.” In some cases agencies have gone by the book, and sometimes the delays are short.

But often agencies just announced longer rule suspension without going through the legal process, Hammond says. In April, for instance, the Department of Transportation delayed the compliance date for a new rule requiring airlines to electronically report incidents of mishandling wheelchairs and baggage by a year—from January 2018 to January 2019. The agency cited two main reasons: the White House regulatory freeze order and requests for more time from the industry group Airlines for America and Delta Airlines.

Hammond says this delay appears to be illegal. “Memos issued by the presidential administration cannot trump statutory requirements,” she says. “The agency seems to be lacking both a reasoned explanation and any source of authority for failing to undertake notice and comment for the purpose of changing the rule's deadline.” A Transportation Department spokesperson, who asked not to be identified, says carriers had been granted extra time to ensure accurate data collection. The department did not respond when asked for a legal justification.

Sen. Tammy Duckworth (D–Ill.), an Army veteran injured in the Iraq war who uses a wheelchair, wrote a letter to Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao asking for an explanation. Chao’s response contained no legal justification either; it cited the inconvenience implementing the rule would cause airlines. “Carriers have encountered challenges, such as reprogramming computer systems, developing procedures to account for gate-checked bags and training personnel,” she wrote.

Duckworth is not mollified. “Far too many Americans living with a disability—many of whom are veterans—face unnecessary challenges during air travel,” she said via a spokesperson. “Two of my wheelchairs were broken outright by airlines while I was traveling and it was the equivalent of having my legs taken away from me again. This rule would go a long way towards ensuring the airline industry protects its passengers and treats them with the respect they deserve.” She has included language in the Senate’s Federal Aviation Administration reauthorization bill to restore the effective date of the rule to January 2018.

For agencies and industries, legal battles and political flack may have an advantage over reopening the regulatory process. “There’s a long game and a short game an agency head is playing,” says University of Pennsylvania Law School professor Cary Coglianese, who directs the Penn Program on Regulation. The long game is the overall strategy of rolling back regulations. “One short game may be, ‘let’s see what we can get away with,’” Coglianese says. “There was very little to be risked by EPA just postponing the methane rule and seeing if they could get away with it.” Losing the court fight simply means a rule that was already on the books will proceed. For companies, delaying a rule’s implementation date for even a few months can save money. Their legal fees may be less than the capital investments required by rule compliance. “It’s often cheaper for industry to pay for lawyers to litigate and slow things down than it is to comply with a new rule,” Steinzor says.

But now the methane rule decision could give advocacy groups a clearer argument to end the slowdowns. David Baron, an attorney with the environmental group EarthJustice, which took part in the ozone and methane suits, says groups are preparing to spend a lot of time in court trying to compel agencies to enforce their own regulations. “The delays have been precipitous and our view unlawful in almost all of these cases,” he says. “And so far, anyway, the courts have agreed.”