On the evening of February 21, 1885, two Scottish meteorologists living atop Ben Nevis—the highest peak in the U.K. at some 4,400 feet—attempted to make their appointed hourly measurements. But the tempestuous elements had other ideas: The roaring winds ripped their notebook in two and blew it away. The lanterns wouldn’t stay lit long enough for the men to read the thermometers. And when the intrepid observers tried three times to venture out into the raging storm, they had to be hauled back in by rope. “After that the observer did not go out," the log book entry for the evening dryly notes.

In the two decades from 1883 to 1904 a group of hardy, dedicated men braved these howling winds, bone-chilling temperatures and almost ever-present fog to faithfully gather meteorological observations nearly every hour of every day from their observatory perched above the Scottish Highlands. They were explorers of the atmosphere, akin to their Victorian contemporaries who launched expeditions to the South Pole, says Ed Hawkins, a climate scientist at the University of Reading. They were also, he says, “slightly crazy.”

Once a source of Scottish scientific pride, their work had largely been forgotten, their data filed away in little-used bound volumes in the Edinburgh Meteorological Office archives. Now Hawkins and his colleagues have launched an effort to “rescue” the nearly two million data points the weathermen worked so hard to gather, asking volunteers to type them into a database column by column. The data will help scientists like Hawkins improve model predictions of how the climate will change as global temperatures rise by filling in gaps in the historical record and providing more context for today’s weather extremes. “If we’re going to put things in context, we need to have a much longer context to put things in,” Hawkins says. He had been casting around for a data-rescue project when he heard the story of the Ben Nevis observatory from Marjory Roy, a retired U.K. Met Office employee and Edinburgh native who came across the trove of records in the 1980s and later wrote a book about the efforts, The Weathermen of Ben Nevis.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The weathermen, from left to right: A. Rankin, R.T. Emond and R.C. Mossman.

Credit: Royal Meteorological Society collection, held as part of the Met Office archive at National Records of Scotland

During storms, the winds at the summit were (and still are) ferocious, reaching up to 120 miles per hour, equivalent to a category 3 hurricane. In winter the observers didn’t use the anemometer, an instrument for measuring wind speed, for fear it would be damaged by the supercooled water droplets that froze to everything, leaving the observatory caked in windblown ice. Instead, they measured winds by how far they could lean into them, even calibrating against one another and the anemometer. Those winds also frequently buried the observatory in snow drifts, forcing the meteorologists to repeatedly tunnel out or use a second door built into the observatory’s tower.

Although the Ben Nevis data are from a single spot, it is rare even today to have data—especially hourly data—from a mountain peak and from such a northerly location, where the climate is warming at one of the fastest rates on Earth. “There aren’t many hourly observations from any time in history, especially back that far,” says Hawkins, who has climbed “the Ben,” where the ruins of the observatory still sit.

When data like these are included in climate models, it can refine representations of hard-to-capture features such as storms. It takes the picture from a fuzzy, impressionist painting to perhaps a Polaroid—not as clearly resolved as today’s satellite images, but a definite improvement. The “magnificent view” from the peak also allowed the meteorologists to observe phenomena such as the aurora, Roy says. Hawkins says those observations will help fill in gaps in that record as well.

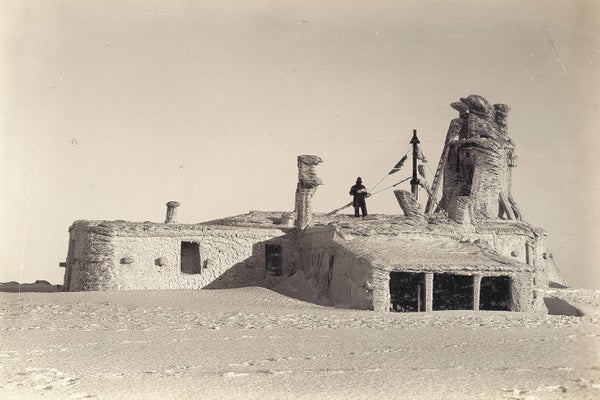

The observatory at the top of Ben Nevis, the highest peak in the U.K.

Credit: Royal Meteorological Society collection, held as part of the Met Office archive at National Records of Scotland

Of course, digitizing such data is a tedious process. Hawkins estimates it would take one person two years to work through the Ben Nevis archive. Hence, the need for a slew of volunteers who can collectively type in temperature, pressure and rainfall data from the scanned-in pages on an easy-to-use interface far faster. (The volunteer effort is fitting, as the observatory itself was crowdfunded; even Queen Victoria pitched in £50.)

In the nearly two months since the new project launched, more than 9,000 people have each entered at least one column of data. Eleven dedicated people have each done more than 1,000 columns. “I liked the thought of helping to preserve this data and making it available for use to current scientists. A small effort from me to help an important project,” says Sheree Lester, a retired IT worker living in the south of England.

Given the volunteer response so far, Hawkins expects they’ll complete the project by early 2018. Then he hopes to tackle more of the millions of pages of old, non-digitized data languishing in archives all over the world. “We do have all this data from the past that is sitting on paper,” he says, “that we know would be very valuable if it was all rescued.”