Communities of color in the U.S. have long reported health problems from heavy exposure to polluted air. In recent decades a growing body of data have bolstered these reports by showing that Asian, Black and Hispanic people are exposed to relatively higher concentrations of potentially deadly air pollution on average, compared with white people. But some policy makers have questioned whether these trends hold across sources of such pollution, which can vary regionally and range from tailpipe exhaust on highways to emissions related to construction or commercial cooking.

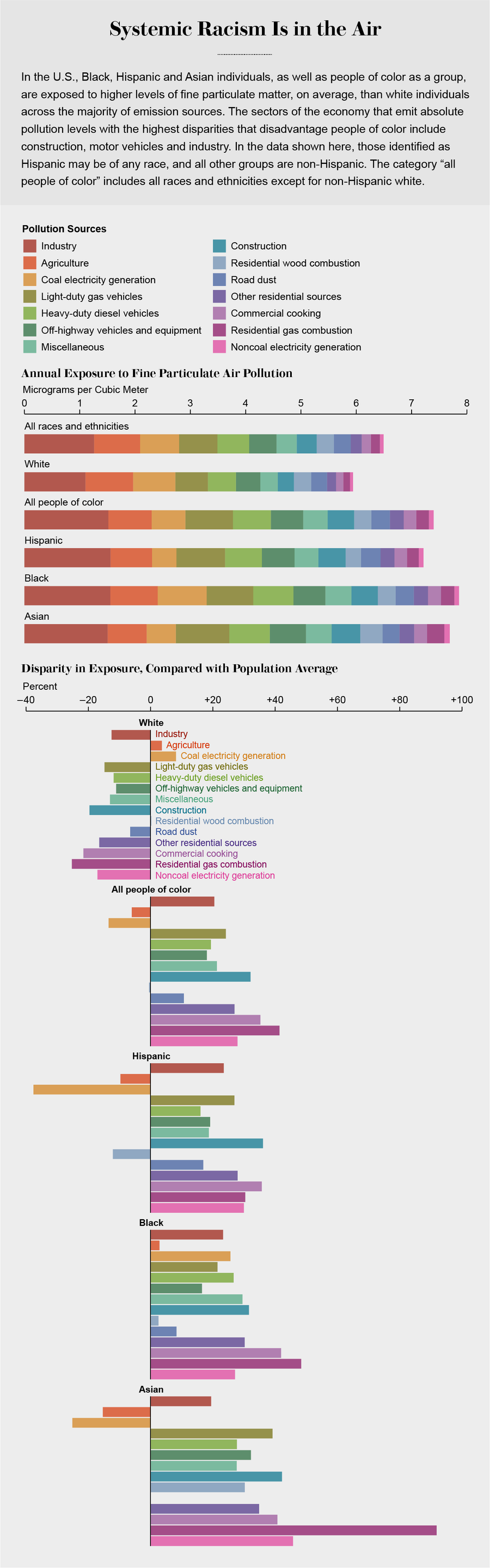

A 2021 study in Science Advances erases a great deal of any doubt that might have existed about racial and ethnic disparities in exposure to air pollution emitted from a variety of sources. The paper reveals that the same exposure disadvantages for people of color collectively persist across 12 of 14 groups of emission sources that spew a particularly dangerous type of air pollution: fine particles with a diameter of 2.5 microns or smaller, known as PM2.5. They are small enough to carry hundreds of chemicals deep into the lungs, where they cause respiratory and heart disease. Fine-particle air pollution is one of the largest environmental causes of death globally, according to a 2020 analysis by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington. And sources cited by the newer study show that exposure to such pollution causes between 85,000 and 200,000 premature deaths in the U.S. annually.

The air pollution impact on each racial or ethnic minority group—Black, Hispanic and Asian people—persisted even when the researchers controlled for the state in which people resided or for whether they lived in an urban or rural region. And the disproportionate pollution impact held among people of color as a group regardless of household income.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The researchers also break down the relative source-exposure trends for each minority group, compared with those for white people, whose overall exposure is lower than the national average. Hispanic and Asian people are exposed to higher-than-average concentrations of fine-particle emissions from most of the different source types, the analysis shows. For Black people, the exposure disadvantage holds across all 14 groups of emission sources.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: “PM2.5 Polluters Disproportionately and Systemically Affect People of Color in the United States,” by Christopher W. Tessum et al., in Science Advances, Vol. 7; 2021

“When we started this project, we were thinking that we would see what the main sources of air pollution are behind this injustice—and then we could say, ‘We can fix those and solve this problem,’” says study leader Christopher W. Tessum, an environmental engineer at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “What we found instead is that it’s actually almost all of the source types of air pollution that are causing the disparity. It’s really just everything that’s stacked against people of color and exposing them more to air pollution.”

Fine-particle pollution emissions from construction, motor vehicles and industrial sources are often among the largest disparities in average exposures of ethnic and racial minority groups, compared with exposures of white people, the team found.

The results are not surprising, says environmental engineer and environmental justice researcher Regan Patterson, who was not involved in the study. But they are significant for the role they can play in substantiating the experiences of the Black community and other communities of color with air pollution and its ill effects—particularly when community members and advocacy groups give testimony about environmental impacts at public hearings or push for policy changes.

“A lot of community organizers have been doing this work; however, it’s important to have the data because it is often stated that if there’s no data, it doesn’t exist,” says Patterson, a transportation equity research fellow at the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation.

To estimate the fine-particle pollution sources’ impact on racial and ethnic groups, the team started with 2014 data from the Environmental Protection Agency’s National Emissions Inventory. The researchers ran a computer model to trace the average concentrations of fine-particulate matter emissions caused by more than 5,400 types of pollution sources, yielding exposure levels affecting regions at the level of neighborhood blocks. The sources were grouped into 14 types of emitters, and the concentrations were mapped to racial and ethnic self-identification data from the U.S. Census.

Tessum says the findings point to a problem inherent in clean-air policies that have successfully reduced air pollution nationwide in recent decades: such strategies will not eliminate the extra air pollution and associated health risks experienced by people of color.

And the strength of the racial and ethnic trends across the dozen or more groups of emission sources suggests that solutions to these air pollution disadvantages are not as simple as targeting a single industry or eliminating certain types of industrial steam boilers or other equipment. “What popped out to us was just how pervasive the problem was,” says University of Minnesota biosystems engineer Jason Hill, a co-author of the paper. “It’s systemic. I’m not going to beat around the bush: this is the product of a long history of racism in this country.”

Patterson says efforts to reduce air pollution should target and benefit disproportionately affected communities and should address inequities that persist despite existing national or broad-stroke regulations.

To eliminate the air pollution burden on people of color and the larger consequences it has for society, Tessum says policy makers should also ensure that discussions of regulatory remedies are primarily guided by the experiences, needs and hard-won expertise of the affected communities—and by organizations that advocate for those who are most affected.