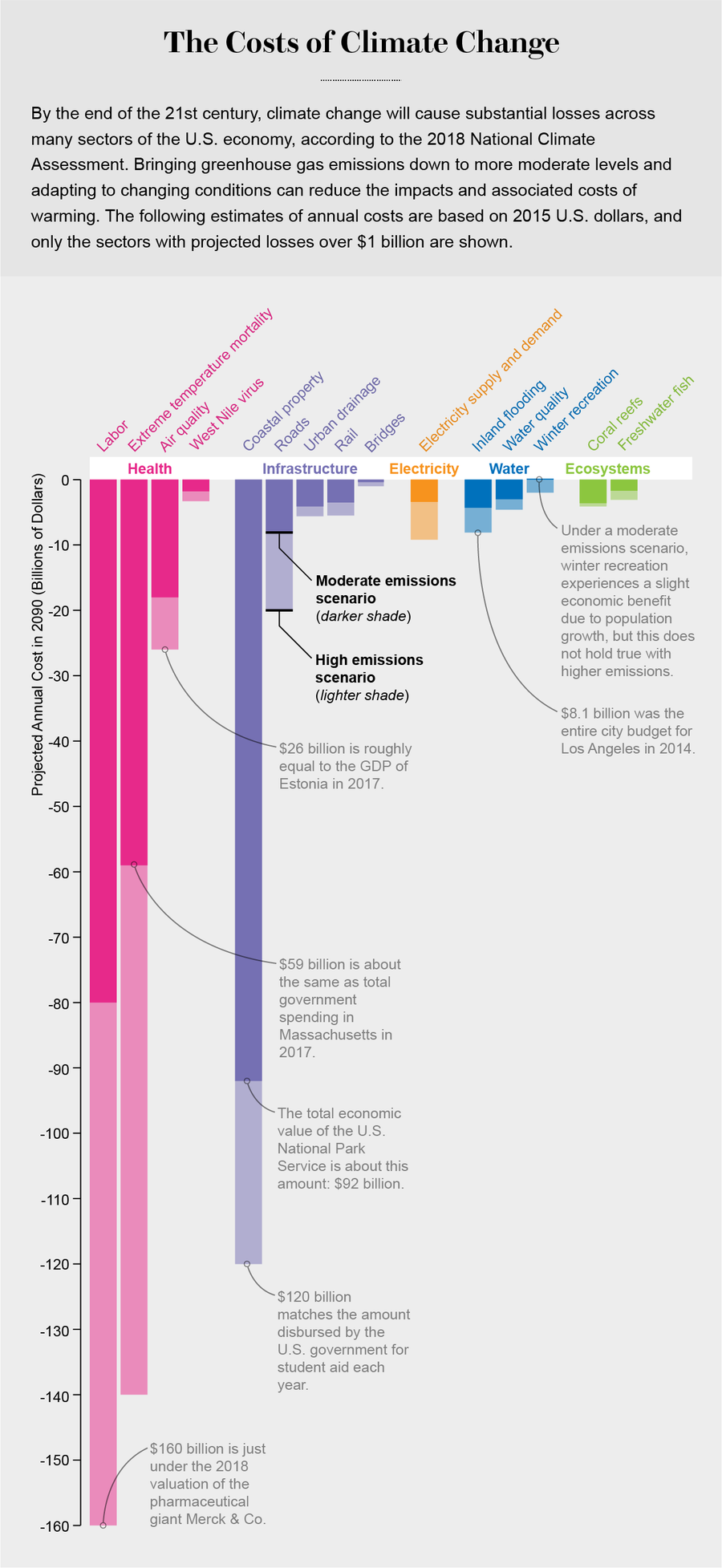

Climate change comes with a hefty bill. The United States stands to experience major economic losses over the 21st century as sea levels rise, heat waves become more frequent and rains fall in heavier bursts, according to the recently released National Climate Assessment (NCA). Sources of the costs range from damaged and abandoned coastal properties, to wages lost when it is too hot to work outdoors, to premature deaths caused by increased air pollution and disease exposure.

The report is put together by 13 federal agencies and includes input from hundreds of scientists, including many who work at academic institutions. Released every four years by Congressional mandate (this year’s NCA weighs in at 1,656 pages), it uses projections of climate change based on varying levels of greenhouse gas emissions—and figures in expected population changes—to estimate the toll a changing climate may exact on various sectors of the country’s economy. In the graphic below, Scientific American focuses on the sectors subject to the biggest impacts and compares the projected losses to current economic activity. Even for sectors in which the overall numbers seem relatively small, those involved can be hit hard. For example, losses in freshwater fishing would be felt disproportionately by small communities that depend on fishing-related tourism.

The NCA estimates are not intended to be exact predictions for specific years. Rather, they provide a sense of the scale of damage climate change may cause by the end of the century—and they show the major difference that reducing greenhouse gas emissions and adapting to changes can make in the losses sustained. When it comes to lost hours of labor, for example, reducing emissions could cut the costs in half. And lowered emissions, combined with adaptations such as bolstering protective wetlands and buying out precarious properties, could avoid 90 percent of the costs that could be incurred by coastal areas.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The loss estimates should also be considered conservative because they do not factor in every way climate change might cause damage, according to the Environmental Protection Agency analysis the NCA drew from. For example, the costs of air pollution in this year’s report only included premature deaths linked to increased ozone, leaving out other pollutants.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: Environmental Protection Agency, “Multi-Model Framework for Quantitative Sectoral Impacts Analysis: A Technical Report for the Fourth National Climate Assessment”; May 2017