It has been a tough year for wildlife tourism. Last month the Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden faced worldwide criticism when officials there were forced to kill Harambe the gorilla after a young child fell into the ape’s enclosure. A few weeks earlier a Yellowstone National Park bison calf was euthanized by rangers after tourists had handled it and put it in their car. And just last week authorities in Thailand uncovered gruesome evidence of abuse and wildlife trafficking at the world-famous Tiger Temple outside of Bangkok.

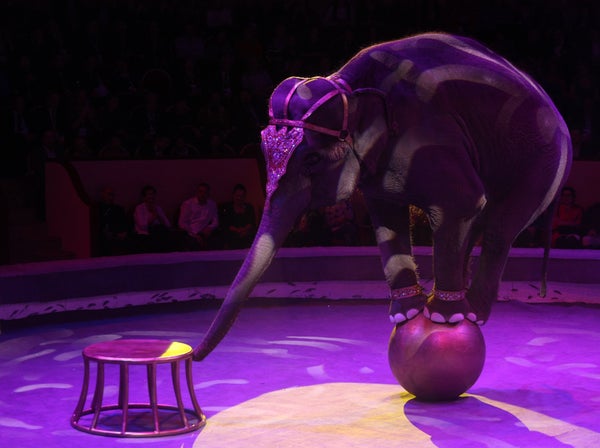

The tragic events come just a few months after two victories, each of which followed years of campaigns by animal rights groups. Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus revealed in January that it would retire its famous performing elephants and send them to live at a sanctuary in central Florida. Then in March the SeaWorld theme park chain, spurred by public reaction to the documentary Blackfish, declared that it would end its controversial killer whale breeding program.

With Harambe’s death death still heavy on peoples’ minds, many have begun to question the role of such facilities in conservation. Some believe this could be the beginning of the end of public acceptance of captive animals, a trend that has been dubbed “the Blackfish effect”. “I think there’s definitely good progress being made,” says Adam Roberts, CEO of the animal rights organization Born Free USA. “This concept of animal attractions as entertainment is starting to disappear.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Others are not so sure. “There’s a positive trend, but it’s kind of a drop in the bucket,” says Luke Hunter, president and chief conservation officer of Panthera, an organization devoted to protecting big cat species. “There are still widespread problems in many parts of wildlife tourism.”

Wildlife tourism accounts for 20 to 40 percent of the total $1 trillion annual tourism industry and involves as many as 900,000 animals around the world, PLoS ONE reported in a paper published last year. The paper ranked all types of wildlife tourism according to their impacts on animal welfare, and found that only a handful of activities—such as mountain gorilla ecotourism in Uganda and Rwanda and some elephant sanctuaries in South Africa and Thailand—have both positive conservation values and animal welfare components. Most other worldwide wildlife tourism activities—including elephant rides, street-dancing monkeys, dolphin interactions and snake charming—were found to have the opposite effect.

Many of these operations may actually be increasing around the world. “From my perspective, wildlife tourism is a growing phenomenon,” says one of the PLoS ONE paper authors, Neil D’Cruze, a researcher with the Wildlife Conservation Research Unit at the University of Oxford and at World Animal Protection, an animal welfare organization. He sees more and more people participating and revenue from these activities soaring.

Wildlife tourism, experts point out, affects a vast variety of species. A 2013 report from the United Nations Environmental Programme’s Great Apes Survival Partnership estimates that thousands of chimpanzees, orangutans and gorillas are “stolen” from the wild each year to be sold into the illegal pet market or to disreputable zoos and other tourist attractions. And Zimbabwe last year sold Chinese zoos 24 elephants, at least one of which reportedly died soon after arrival.

Even the capture and sale of wild killer whales—the practices excoriated in Blackfish—appear to be increasing. Whale and Dolphin Conservation’s (WDC) Far East Russia Orca Project received reports of at least 16 killer whale captures in the Sea of Okhotsk off Siberia over the past three years, with the animals supposedly destined for life in Russian or Chinese aquariums. Orca captures have “exploded” in recent years, says Erich Hoyt, project co-director, who added that Russia has established a quota for up to 10 killer whales to be captured per year. “These quotas fly in the face of scientific advice as they were awarded despite Russian marine mammal scientific advisory body recommending a zero quota in 2014 and 2015,” he says.

Killer whales aren’t alone. “The demand for whales and dolphins acquired from the wild continues to grow,” says WDC campaigns manager Courtney Vail, pointing to recent reports that the infamous Taiji dolphin hunt in Japanlast year resulted in the sale of 117 dolphins to unaccredited aquariums or directly to wildlife dealers. Information on where these animals end up remains sketchy, but the Web site Ceta-base.org tracks dolphins and whales at hundreds of facilities around the world.

Large animals are not the only ones involved. Smaller creatures such as slow lorises, sugar gliders, and even owls and cobras find themselves caught and sold to create photo ops for tourists, says Anna Nekaris, a professor of anthropology at Oxford Brookes University in England. “The smaller the animal, the more likely it is to have been taken from the wild for a short life as a prop,” she says.

The biggest problem with many of these activities, experts say, is that operators tell tourists that they are benefitting conservation by displaying animals. “They claim significant conservation outcomes,” Panthera’s Hunter says. “They claim it’s good for the species. But they don’t contribute in that sense.” He points to South Africa’s popular lion cub petting enterprises, which breed the big cats indiscriminately and then discard them once they become older and too dangerous to be around tourists. Many of these adult lions, as shown in the documentary Blood Lions, end up being sold to facilities that allow “canned hunts” in which shooters can bag a trophy without the trouble of tracking it down in the wild.

Hunter feels activities like lion petting effectively steal funds from legitimate conservation activities such as those of national parks. “I’m convinced that every well-meaning person who has an extraordinary experience there believes they’re contributing to helping the species,” he says. “They want to know that the money they spent is going to conservation. It seems credible because people just don’t know better.”

Oxford’s D’Cruze says it is important that people ask questions to help understand if a facility treats its animals decently. “Where are the animals taken from? Are they put back in the wild? Are people paying for these animals or breeding them so they can sell them? What’s the actual business model of that facility?” He says the answer is not as simple as “wild animals equals good, captive animals equals bad.” He recently returned from a tiger research trip to India, where he saw tourism take a wrong turn in a national park. “There were jeeps going all over the place hounding this one animal,” he says.

Roberts of Born Free adds he has seen the same thing with lion safaris in Africa, where drivers sometimes “inch closer and closer” because they think it will create a better experience for paying tourists. “That detracts from the natural life of the animal, and it also becomes dangerous for people,” he says.

Despite the dangers many of these activities still pose, progress is being made. This past March more than 100 travel agencies around the world pledged to stop supporting elephant rides, and the U.S. enacted new regulations in April that will help protect captive tigers from interstate trade and block roadside zoos from letting tourists handle or feed the cubs of tigers or other big cats.

In Thailand, meanwhile, authorities have over the past two weeks seized all of the tigers living at the infamous Tiger Temple just outside Bangkok. The site has been a popular tourist destination for a decade, but the first day of seizures also uncovered 40 dead tiger cubs in a freezer, possibly backing up conservationists’ long-standing complaints that the facility did not have its animals’ welfare in mind and were using the big cats to feed the demand for tiger body parts to be used in traditional Asian medicine. To date 22 people working at the temple, including three Buddhist monks, have been arrested and charged with wildlife trafficking. Conservationists have long expressed fears that the temple was supplying tiger bones and other products for smuggling to China and other countries.

Roberts calls this kind of progress “really important. It sends a message,” he says. He added, though, that “work is far from done” and that change happens “in a long-term, progressive manner.”

Hunter, meanwhile, says there are thousands of good examples of wildlife tourism around the world, including everything from national parks to private reserves. “They foster encountering animals living in the wild with as little interference as possible,” he says. Those activities, in turn, generate millions of dollars for local communities and benefit wildlife without putting animals’ lives at risk for the sake of a selfie.