Cities around the globe are expanding. Woodlands, farms and deserts are being paved over with roads, a transformation that is virtually irreversible—and one that can have profound consequences for global warming, depending on how sprawling the streetscapes are. Researchers have now found that city and suburban streets around the world have become less connected over the past four decades, encouraging modes of transportation that are less climate-friendly.

The new study, published last month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, differed from previous papers in its approach to measuring urban sprawl. Instead of looking at how spread out residents are or how much land a city covers, the researchers created an index based on how efficiently connected streets are—in other words, how far one would have to travel to get from one point in the city to another. In a loosely connected street system filled with dead ends, roads leading to gated communities or isolated routes stretching to far-away neighborhoods, people are more likely to drive cars—a major source of greenhouse gas emissions—says study co-author Christopher Barrington-Leigh, an economist at McGill University’s School of Environment. On the opposite end of the spectrum, if streets form a tight grid, routes are shorter, walking is more convenient, and investing in public transit is more palatable to municipal governments. “The choice of the initial road layout in new development could be one of the biggest climate-relevant investments that humans are making,” Barrington-Leigh says. “And yet it’s not getting a lot of attention in policy circles.”

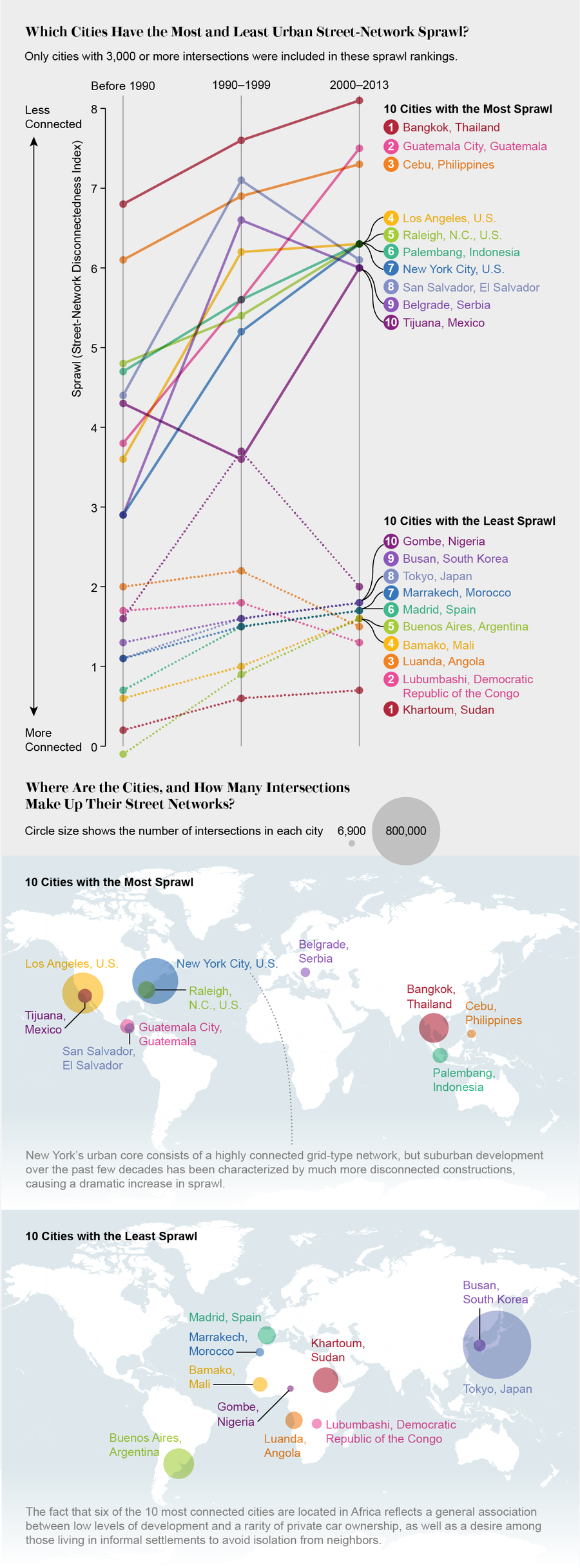

He and his colleagues used satellite images taken between 1975 and 2014 to document when streets started to snake through farmlands and other outlying areas around 200 cities. They analyzed the information using a measure they created called the Street-Network Disconnectedness Index, or SNDi. The more a city featured large numbers of dead ends or greater distances between intersections, for example, the more “sprawl” it was designated to have—and the higher its SNDi score was. “Their approach is quite novel,” says Richa Mahtta, a research associate studying urbanization and resource use at Yale University, who was not involved in the work.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: “Global Trends Toward Urban Street-Network Sprawl,” by Christopher Barrington-Leigh and Adam Millard-Ball, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, Vol. 117, No. 4; January 28, 2020

The researchers found that streets in the U.S. sprouted out from cities faster than anywhere else on earth until they reached a peak in the mid-1990s. Though its streets have grown gradually more connected since then, sprawl remains worse in the U.S. than in any other country. In most regions, it has steadily increased since 1975, though globally, rates have recently slowed.

A number of factors helped drive city streets’ expansion into U.S. suburbs during the 20th century, according to Harold Platt, a Loyola University historian, who studies cities and the environment and was not involved in the new paper. The invention of electrical grids, telephones and cars near the beginning of the 1900s made living just outside of cities more convenient. And after World War II, white city dwellers flocked to the suburbs, helped, in part, by the incentives for banks to give low-interest home loans to veterans through the GI Bill, Platt says.

Despite Manhattan’s famously tight street grid, New York City ranked among the 10 most sprawling cities of the 200 examinedin the study because of the long roads that have sprouted around the larger metropolitan area. But megacities are not the only ones with a high SNDi. Raleigh, N.C., has much fewer people than New York—but it has the same amount of sprawl, fueled, in part, by a rising population and the presence of highways through and around the city. From such highways, many suburban roads fractally split off into dead ends, according to a 2000 Brookings Institution report and a 2014 PLOS ONE paper. (The graphic accompanying this article only shows the SNDi rankings for a subset of the cities in the study: those with 3,000 or more intersections.)

Numerous cities around the world appear to be repeating the U.S.’s rapid sprawl of the 1970s and 1980s as global populations shift to urban areas. For instance, Bangkok had, by far, one of the most disconnected collection of streets among the world’s major cities during all four decades the new study examined. Thailand’s mid-20th-century economic growth fueled rapid development in its capital. Roads formed expanded grids that contained “superblocks,” or giant swaths of empty land, a 2007 paper in Urban Design International found.

.png?w=900)

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: “Global Trends Toward Urban Street-Network Sprawl,” by Christopher Barrington-Leigh and Adam Millard-Ball, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, Vol. 117, No. 4; January 28, 2020

On the flip side, Japan’s cities have consistently maintained some of most connected street systems—partly because of the City Planning Law, a set of regulations updated in 1968 to limit land development and prevent chaotic urbanization during the country’s economic boom. Many South American cities kept sprawl limited for a time because of the dense grid patterns left by Spanish colonizers. But some—including Guatemala City, which is the fourth most sprawling city in the world—began to spread out in the 1970s. Violent conflicts pushed people to the city’s edges, according to a 2018 study in Cities, and it was again reshaped when informal settlements cropped up after a destructive 1976 earthquake.

One reason for the growth of sprawl is that new streets tend to mimic existing ones, according to earlier research by the PNAS paper’s authors. A developer building new roads next to a walkable grid will have good reason to make them walkable as well, Barrington-Leigh says. “By contrast, if I’m building next to an impenetrable cul-de-sac, not only are there no services to walk to there, but I can be pretty sure there aren't going to be,” he adds. “In fact, I can even be pretty sure that the chances of the local government putting in transit there is relatively low,” so it makes sense for developers or city planners to continue adding more unwalkable and disconnected roads.

The U.S.’s peak and subsequent decline in such streetscapes shows that even rapidly sprawling countries can change course. The U.S. reversal can be attributed to a number of factors, including urban planners who embrace new urbanist design principles such as gridded streets and policy makers who prioritize street connections, according to Barrington-Leigh’s previous research. Several U.S. cities have banned culs-de-sac, for example. Others have written gridded streets into their building codes. Barrington-Leigh hopes the new research helps foster such policies. Mahtta thinks it could because it “actually calls for a need for relevant action,” she says. “[It] highlights where we can start.”