West Virginia is grappling with one of the largest reported hepatitis A outbreaks in U.S. history. The disease flare-up has sickened at least 1,031 people this year, and some health officials say the surge is linked to the ongoing opioid crisis and other drug use.

About 80 percent of those known to be infected in the outbreak say they use illicit drugs, according to state records. Although health officials do not know exactly which substances are involved, self-reported data from hepatitis A patients indicate about 58 percent inject illicit drugs and 42 percent use noninjected ones; some report using both. A number of the patients specifically mention heroin, according to the West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources (DHHR). “This is a wake-up call—here is another impact of the opioid epidemic,” says Rahul Gupta, West Virginia’s state health officer and the DHHR commissioner of Public Health.

Local health officials say many of those infected may also be using methamphetamine, which is not an opioid. “I’m sure the opioid crisis has fueled this outbreak but a lot of people are using methamphetamines, so I don’t want people to think it is only opioids. I would link this more to overall drug addiction,” says Janet Briscoe, director of epidemiology and emergency preparedness at Kanawha-Charleston Health Department, which oversees the county reporting the most cases in the current outbreak. Further studies with the assistance of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) may help uncover more specifics, says Gupta, who is both an epidemiologist and a clinician.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Hepatitis A cases in the U.S. have often been linked to contaminated food. The disease is also associated with poor hygiene among those struggling with homelessness or inadequate housing conditions, which can sometimes accompany addiction; the illness can be transmitted by unwittingly ingesting traces of fecal matter or by being exposed to them during sexual contact.

Hepatitis A infection rates across the U.S. have declined by more than 95 percent since a vaccine first became available in 1995. But in the past few years rates have ticking upward again due to large, multistate outbreaks—inflamed, some experts say, by an increase in homelessness and drug use. “The data supports that,” Briscoe says. “When you define homelessness, most of us think of someone being out on the street or living in an encampment, but that’s not always so. We are seeing people go from place to place and go between shelters, staying with family and friends, then maybe living in their car.”

West Virginia has been hit particularly hard by the opioid crisis—in 2016 it had the highest rate of opioid-related overdose deaths in the U. S., at 43.4 deaths per 100,000. The state has struggled with both prescribed opioids and illicit ones, including heroin.

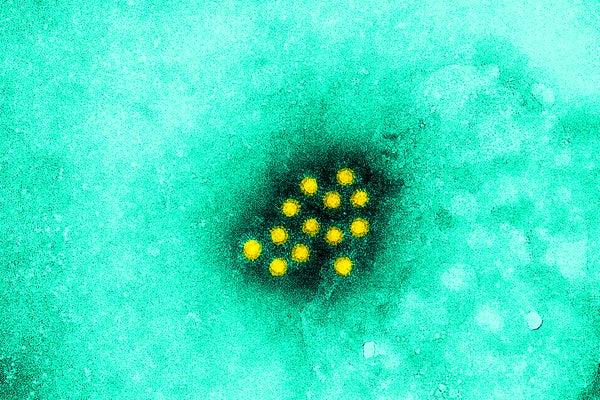

Sequencing of viral genomes indicates West Virginia is battling the same hepatitis A strain that has hit homeless communities and illicit drug users in neighboring Kentucky as well as in California. In West Virginia about 12 percent of the cases occurred among people experiencing homelessness. Other high-risk groups include the recently incarcerated, and men who have sex with men. The virus, which attacks the liver, is easily transmitted via sexual or oral exposure to even microscopic quantities of infected feces; it can be as simple as touching a contaminated surface like a subway pole or bathroom door and then eating lunch without first washing one’s hands. The disease can be highly contagious up to two weeks before an infected individual shows any symptoms, which include nausea, fever and sometimes yellowing of the eyes or skin. In patients with underlying liver disease it can cause liver failure, potentially leading to death. In West Virginia it has killed at least two people this year.

Along with thorough hygiene, vaccinations can also beat back the spread of the illness. West Virginia’s Bureau for Public Health has provided more than 18,000 doses of hepatitis A vaccine amid the current outbreak. Yet limiting the spread of the disease remains challenging due to the ease of transmission. West Virginia health officials announced Wednesday they have requested help from the CDC to tamp down the outbreak, as directed by Gov. Jim Justice. “There are six people here from CDC,” says John Law, a spokesman for the Kanawha–Charleston Health Department. The CDC team is performing duties including case investigation and data management work.

The West Virginia outbreak has included at least 37 restaurant workers—mostly in Kanawha County—but there has been no confirmed transmission from employees to diners. Still, “We have asked restaurants to require their employees to be vaccinated for hepatitis A in Kanawha and are providing vaccine at no cost to those employees who are uninsured,” Gupta says. (Health officials, however, cannot force employees to be vaccinated.) To assuage customer concerns, multiple restaurants in that area have put up window signs noting their involvement with vaccination efforts.

The good news, Gupta says, is that inoculation with the hepatitis A vaccine—even up to two weeks after exposure to the virus—can offer some protection. Unlike the flu virus, which usually sickens people within a few days of exposure, the incubation period for hepatitis A can be as long as two to seven weeks.