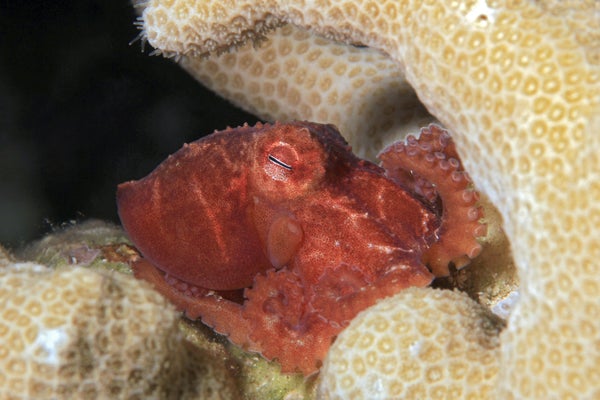

An octopus nestles under a rock, but she’s still within reach of the shark following her scent. The shark bites down on one of her arms and rolls over again and again, twisting the limb trapped between its jaws until it detaches. The shark swims away with the arm in its mouth, spitting out sand and rocks acquired in the scuffle.

Where her arm used to be, the octopus has a stub of bright-white flesh. She retreats from the site of the encounter slowly and without her usual flair, almost crawling along the seafloor on her way back to her den.

The scene is from My Octopus Teacher, a film nominated for Best Documentary in this year’s Academy Awards, which will take place on April 25. Human viewers empathize with this cephalopod, whose intelligence and curiosity are apparent in the documentary. But what might she have experienced during the gruesome shark attack?

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Until recently, there was no rigorous research showing that invertebrates experience the emotional component of pain. A study published in iScience in March provides the strongest evidence yet that octopuses feel pain like mammals do, bolstering the case for establishing welfare regulations for these animals.

The experiment, says Lynne Sneddon, a fish pain researcher at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, who was not involved in the study, “shows beyond a doubt that [octopuses] are capable of experiencing pain.”

Much of what we might think of as a reaction to pain, such as pulling your hand away from a hot stove, is actually a reflex. It happens automatically, without involving the brain, in almost all animals with a nervous system.Pain is a two-part experience that occurs in the brain. The first part is awareness of a physical sensation, such as the throbbing of your burned hand. The second, more complicated part is the emotional experience associated with that sensation: realizing that your throbbing fingers and blistering skin are causing discomfort.

It is this emotional aspect of pain that is relevant for animal welfare, ethicists say. But it is difficult to measure. “I don't think there’s any way of proving that another organism, even another human, actually, is experiencing conscious pain the way that we ourselves do,” says Terry Walters, a pain researcher at McGovern Medical School at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, who gave feedback for an early draft of the study but was not directly involved. The closest we can get for other species, he says, is determining what situations and experiences they try to avoid.

That is what Robyn Crook did using a so-called conditioned place preference test at her lab at San Francisco State University. This test is a common method of determining whether mice and rats are experiencing pain, and she found that octopuses behave like their mammalian counterparts in the assay.

During the experiment, Crook placed a Bock’s pygmy octopus between two chambers, one with stripes on the walls and the other with spots. Both patterns were new to the animal and intended to catch her attention. The researcher then let her roam around and observed where she lingered.

The next day, in another part of the lab, Crook injected a small bead of acetic acid into one of the octopus’s arms. She says doing so is like squirting lemon juice on a paper cut. When the animal awoke with a stinging arm, Crook confined her to whichever chamber she had preferred before.

The researcher removed the octopus 20 minutes later and administered lidocaine to numb her arm. Crook then placed her in the chamber she had not liked as much at first. After another 20 minutes, Crook returned her to her home tank.

Finally, about five hours later, Crook brought the octopus back to the chambers and gave her a choice: return to the initially preferred chamber, where she was confined with a stinging arm, or go to the one she had not liked as much but where she was numb. “All we’re asking is, ‘What do you remember feeling in those two places?’” Crook says. She ran the experiment with seven octopuses. They consistently chose to go to the second, nonpreferred chamber. As a control, Crook injected seven other animals with saline instead of acetic acid. Unlike the experimental group, those octopuses returned to the room they had originally preferred.

The results show the cephalopods’ complex pain experiences. They associated the chamber they had once liked best with the stinging they felt the last time they were there, even though the injection occurred somewhere else. Then they compared that experience with their typical pain-free state and decided that how they usually felt was better. “That’s the sort of big cognitive leap you have to make to be able to do this particular learning experiment,” Crook says. Using all that information, the octopuses chose to go to the nonpreferred chamber. “There’s a lot of conscious processing that has to happen,” she says.

Walters thought Crook’s experimental setup was elegant and thorough in devising a test for emotional pain in octopuses. “She did it in a way that is more systematic, more complete, more careful than anybody's ever done with any invertebrate,” he says.

As the octopus from My Octopus Teacher recuperates in her den, swimmer and filmmaker Craig Foster checks on her daily. He feels deeply connected to the animal, and she may feel connected to him. It is hard to say.

Crook’s latest study suggests that there ought to be more focus on the welfare of these animals, which are currently unprotected in both research and industry in the U.S.. In this country,animal welfare regulations apply only to vertebrates—they use a backbone as a proxy for the complexity of an animal’s brain. Crook’s work challenges that assumption by demonstrating emotional pain in tiny octopuses. Meanwhile unregulated use of the cephalopods continues at a small scale in labs and at a much larger scale in the food industry. There is even talk of farming octopuses for food. “It’s not clear at all that’s a good idea. It’s very possibly an extremely bad idea,” says Jonathan Birch, an animal sentience researcher at the London School of Economics and Political Science, who was not involved in Crook’s study.

Historically, findings that, like Crook’s, indicate that a creature’s brain is more complex than previously thought, combined with changes in public perception about the treatment of animals, have led to increased protections, she explains. “We see this very slow broadening of our circle of concern,” Crook says. As her research strengthens the scientific case for welfare regulations, popular works such as My Octopus Teacher could help shape public opinion.

“It generates curiosity and concern for ocean habitats, and I think that’s a great thing,” Crook says. “If what comes out of it is more general public concern for the lives and deaths of octopuses and other cephalopods, then that’s also great.”