An internet battle has been raging for more than a decade over so-called “net neutrality,” the principle that internet service providers and governments treat all content equally, prohibiting the indiscriminate blocking or slowing down of certain material. The issue pits broadband providers—who are fighting to limit government regulation of their services—against online companies that rely on the internet’s impartiality to stay in business.

The net neutrality debate rests largely on hypothetical scenarios—for example, that broadband providers will favor content providers like Netflix and Google that are capable of paying more for faster download speeds. The unresolved issue has spawned another, more tangible problem, however: Broadband providers are unwilling to invest in the infrastructure needed to reach the poorest parts of the U.S.

More than a third of Americans living in rural areas—23 million people—lack access to broadband, which the Federal Communications Commission in 2015 defined as internet speeds of 25 megabits per second (Mbps) for downloads and 3 Mbps for uploads. The scarcity of high-speed broadband service in rural America might not seem like a problem poised to grab Congress’s attention when it returns to Washington from recess. Still, it is a concern closely tied to many other issues facing lawmakers and their constituents, including the availability of education, jobs and telecom-provided health care services in underserved areas.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Different studies disagree over broadband companies’ contention that government regulation stifles investment in internet infrastructure. By giving the FCC the power to regulate how internet services are delivered and priced, the 2015 Open Internet Order, they say, makes the already risky investment of installing high-speed fiber-optic lines to remote, sparsely populated regions even riskier if the FCC decides to, for example, regulate how much broadband companies can charge for their services. Giant internet companies including Netflix, Google and Facebook counter that the Open Internet Order is necessary to ensure start-up companies—which all of these once were—can reach the same online audience as their larger competitors.

Ajit Pai, chairman of the Trump administration FCC, has vowed to roll back the order. But his efforts could just as easily be reversed the next time the Democrats control the FCC, argues Rick Boucher, a former U.S. congressman (D–Va.) who chaired the House Energy and Commerce Committee’s Subcommittee on Communications and Technology. Boucher notes that broadband providers—worried about even the possibility of greater government oversight of how internet services are delivered and priced—avoid making the investments needed to extend their reach into rural regions. These areas make up much of the Ninth Congressional District that he represented for 28 years.

Scientific American spoke with Boucher about the challenges of delivering broadband to rural communities, the role Congress could play in permanently breaking the net neutrality impasse and the potential of emerging technology to deliver broadband over electric power lines, by-passing the dysfunction in the national’s capital all together.

[An edited transcript of the interview follows.]

What are the main difficulties in delivering broadband to remote rural locations?

Rural areas are characterized by their challenging—often mountainous—terrain and long distances between thinly populated places. The costs of deploying fiber-optic (so-called “middle mile”) broadband services are far greater than they would be to deploy [them] in urban centers, and when you do reach a community you may not have a lot of subscribers to pay for the service. Oftentimes in those rural areas—the Appalachian region, generally in the middle West and in smaller towns nationwide—the annual income is below the national average and people are struggling. Even if you have 100 percent of the people in an area subscribe to the service, you might still find it challenging to justify the cost of stringing lines across those distances.

In 2015 the FCC decided to change how broadband is regulated, reclassifying it from a Title I (information) service to a Title II (telecommunications) service. How did this make it more difficult to offer the service to rural areas?

The short answer is that although the FCC under [former Chairman] Tom Wheeler decided not to regulate how providers set their prices, terms and conditions, by reclassifying broadband as a Title II common [telecommunications] carrier service the FCC [gave itself the ability to] move quickly to regulate very intrusively the most intimate details of the service offerings if it chose to do so. The broadband providers naturally stepped back from any plans to invest in telecom infrastructure. These are companies that typically spend tens of billions of dollars every year on deployments [of wire line and wireless internet infrastructure], but they’re not going to spend that much capital in the face of the kinds of regulatory uncertainty that they face with Title II. The effect of that was felt more severely in rural areas because it made a challenging economic case all the more difficult for broadband providers.

How should Congress address the issues of net neutrality and investment in rural internet access?

Net neutrality is the most divisive issue in technology policy, and unfortunately at times has become partisan. It really is time to put it to rest with [a permanent solution]. Unless Congress acts, we’re going to see this FCC move from classifying broadband as a Title II service back to a Title I information service. Let’s suppose that in 2020 a Democrat is elected. Unless Congress has done something by then, you’re going to see the Democratic FCC go back to Title II. You’re just going to get a continual ping-pong, and all that does is prolong the regulatory uncertainty that I was talking about.

What are the prospects for the current Congress acting?

They ought to be pretty good. This is one subject on which there should be bipartisan agreement. The Democrats—generally aligned with “edge” [content] providers such as Google, Amazon and Facebook—have sought to keep broadband providers from interfering with their ability to reach customers. There’s really no disagreement today [from Republicans] on that policy. And ever since [former FCC] Chairman [Julius] Genachowski’s Open Internet Order in 2010, broadband providers have incorporated the principles of an open internet into their business operations. Why not pass a bill in Congress that codifies those rules and gives them statutory permanence? At the same time, you include language in the bill that classifies broadband as an information service, giving broadband providers the certainty they’ve been looking for. Republicans on the House Energy and Commerce Committee announced a hearing recently and said they’d really like to get this done.

My candid view is that as long as the FCC has its notice of proposed rulemaking and is taking [public] comments, then it’s up to the FCC to decide what it wants to do. My guess is that the FCC will do something by the end of the year. Until that happens—with all of the passion that attends that process—it’s unlikely that Congress will step in. So we’re talking about next year as the earliest for serious legislation to be considered.

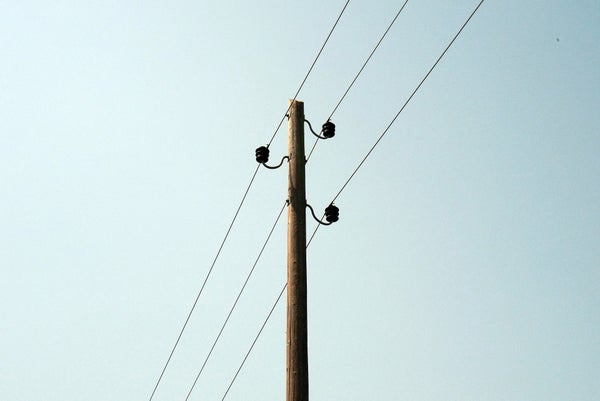

Until Washington can resolve the uncertainty, would technology that delivers broadband over electric power lines fill the void in rural America?

Sure it would. Any sort of platform that exists and could be used to bring broadband into rural areas potentially could be a solution to the problem and reduce the cost of deployment. For this to work, a company like AT&T or Verizon would need to partner with a public utility offering electricity service. It’s going to be facilities owned by the electric utility that are the basic platform for offering any broadband-over-power-line service.

What has prevented broadband services from being delivered by power lines?

There have been technical problems to get the broadband signal to run over the power lines. At one point the transformers were the big problem. They couldn’t figure out a way to get [the broadband signal] around them. So the projects that people had talked about never really got started. It looks like AT&T is experimenting with something unique they call Project AirGig. They’re not planning to send the signal through the power line, they’re planning to send it using the electric field [close to the wire], which is the most innovative thing in the space yet. That’s still experimental, but if it works, it very much becomes part of the long-term solution to getting broadband to rural areas.