When the COVID pandemic led to widespread economic shutdowns and stay-at-home orders in the spring of 2020, many media outlets and pundits speculated this might lead to a baby boom. But it appears the opposite has happened: birth rates declined in many high-income countries amid the crisis, a new study shows.

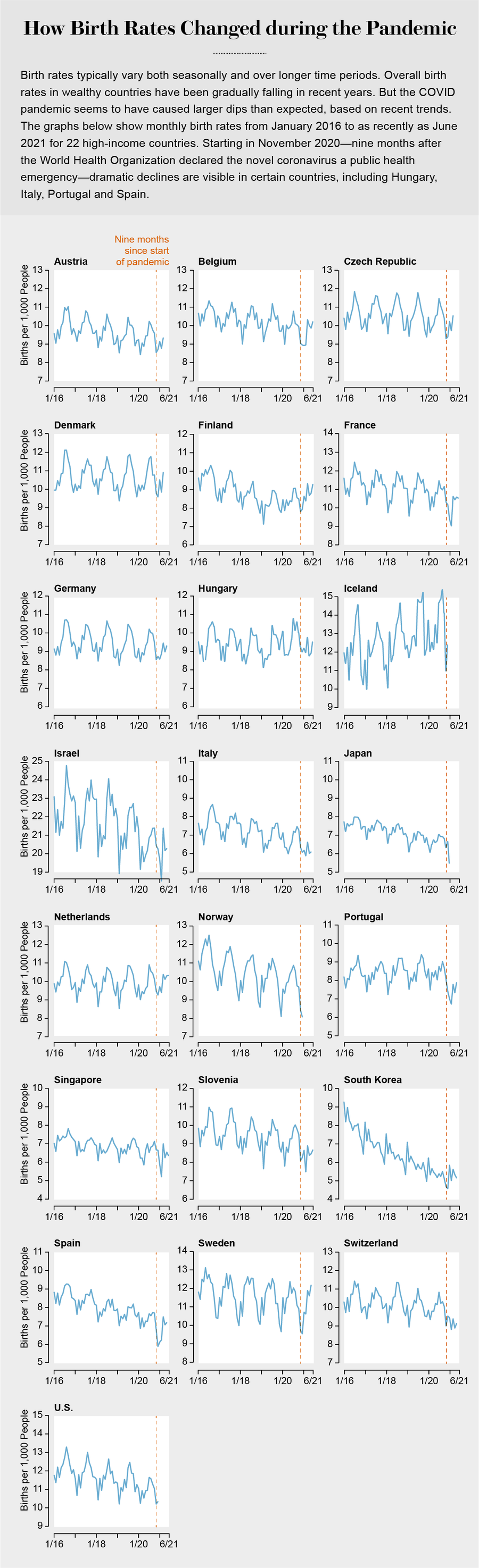

Arnstein Aassve, a professor of social and political sciences at Bocconi University in Italy, and his colleagues looked at birth rates in 22 high-income countries, including the U.S., from 2016 through the beginning of 2021. They found that seven of these countries had statistically significant declines in birth rates in the final months of 2020 and first months of 2021, compared with the same period in previous years. Hungary, Italy, Spain and Portugal had some of the largest drops: reductions of 8.5, 9.1, 8.4 and 6.6 percent, respectively. The U.S. saw a decline of 3.8 percent, but this was not statistically significant—perhaps because the pandemic’s effects were more spread out in the country and because the study only had U.S. data through December 2020, Aassve says. The findings were published on Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA.

Birth rates fluctuate seasonally within a year, and many of the countries in the study had experienced falling rates for years before the pandemic. But the declines that began nine months after the World Health Organization declared a public health emergency on January 30, 2020, were even more stark. “We are very confident that the effect for those countries is real,” Aassve says. “Even though they might have had a bit of a mild downward trend [before], we’re pretty sure about the fact that there was an impact of the pandemic.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Sources: Human Fertility Database, Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research and Vienna Institute of Demography (birth data); World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision, United Nations (population data)

The uncertainty associated with a global pandemic and its impacts on families’ economic circumstances are the most likely reasons for these trends, Aassve hypothesizes. “People don't really understand what the disease is—it is something new to them.... Many people are going to see that their job prospects will be worse, which matters for their income,” he says. “You may not forego childbearing totally, but at least you might postpone it until you see that times are a bit better.”

The findings are not surprising to many demographers, who have noted similar declines after catastrophic events such as the 2008 financial crisis and the 1918 influenza pandemic. But they are still noteworthy.

“We definitely expected there to be a drop in birth rates as a result of the [COVID] pandemic because of the history of disasters in general,” says Philip Cohen, a sociology professor at the University of Maryland, who was not involved in the study. “How it would play out was unclear, so it’s really interesting and important that we’re getting these results now.”

Cohen’s own research, described in a recent preprint study that has not yet been peer-reviewed, has shown that Florida and Ohio experienced birth-rate declines during the pandemic. He found steeper drop-offs in counties that experienced greater numbers of COVID cases and lower levels of mobility. Cohen notes that the PNAS study includes U.S. data through December 2020 and that more recent numbers show a larger decline.

Whether high-income countries will see significant rebounds in their birth rates in the coming months and years remains to be seen. Early data suggest a rebound in births from pregnancies that began in June 2020, following the first wave of COVID infections in countries that were hard hit in spring 2020. But subsequent waves could have caused more people to further delay having children.

The long-term effects of people having fewer babies during the pandemic are a matter of speculation, Aassve says. The phenomenon could possibly lead to an economic boom like the roaring twenties after the 1918 influenza pandemic. Or it could lead to a two-tiered recovery in which some families who were hit hard by the COVID pandemic and its economic impacts might be less likely to have children, whereas others who were less affected or even benefitted might be more likely to do so. A third possibility is that the declines will amount to a blip in demographic terms, with little discernible effect on the population as a whole.

A few countries in the new study, including several Scandinavian nations, Switzerland and South Korea, saw slightly positive trends in birth rates, but they were not statistically significant. Although it is too early to interpret these data, one can speculate that stronger social safety nets may have offset some of the uncertainty associated with having children during the pandemic.

The researchers only included high-income countries in their analysis because of the quality of the data available. Wealthier countries are also more likely to have access to contraception, and women in them are more likely to have greater opportunity and agency.