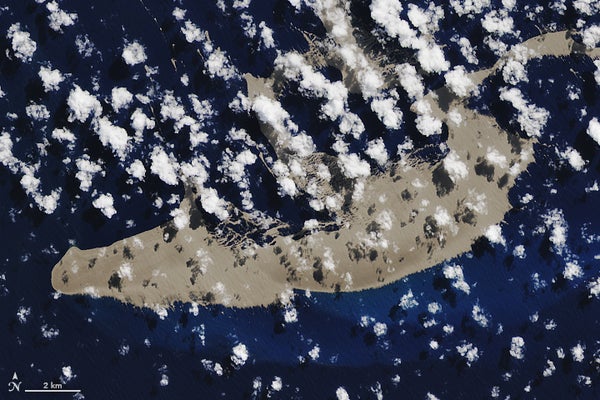

Out of nowhere, NASA satellites recently spotted a huge, flat mass of unidentified material floating in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and heading toward Australia’s eastern coast—home to the Great Barrier Reef. Aerial scans and a few boats have since confirmed that the conglomeration, 58 square miles in area, is pumice coughed up by an undersea volcano.

Such pumice rafts, as they are known, appear occasionally around the world—perhaps once or twice a decade, and always as a surprise. The loose, rocky meshes of stones filled with air holes can float for months, collecting sea life as they go. Photographs of the new raft, still about 2,000 miles from the Great Barrier Reef, have grabbed people’s imaginations. And numerous media accounts have stated that the raft could “save” the reef, large portions of which are dead or dying, by delivering new corals to it.

That scenario is a lovely thought, but is there any science to back it up? Scientific American asked Rebecca Albright to weigh in. Albright is a coral biologist and a curator at the California Academy of Sciences. Her work focuses on understanding how coral reef ecosystems cope with changing environmental conditions.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

[An edited transcript of the conversation follows.]

These rafts are rare, yet scientists have studied a few of them. What kind of creatures do they find?

Probably the best-studied raft resulted from the 2006 Home Reef eruption in Tonga.It floated for thousands of miles. Over time, it collected a lot of different taxa. The most common critters were bryozoans—tiny invertebrates. After that were barnacles, then gastropods [such as snails and slugs], then bivalves such as clams. There were a few sponges, anemones and worms but in very low abundance.

What about corals?

These rafts drift through open ocean for a very long time, so chances are they will run across some coral larvae in the water column. The Home Reef study found that corals constituted less than 1 percent of everything [the researchers] found, and they were primarily in one genus called Pocillopora, a hardy, weedy coral. I would not be surprised if, by the time the pumice reaches Australia, there is a diverse community of things living on it. But will corals be major players? No, absolutely not.

No one knows yet whether the raft will even encounter the reef. But if it does, how would the coral larvae colonize it?

They would somehow have to detach and then attach to the reef. The chances of that are small. There is a phenomenon called polyp bailout, where a polyp of coral leaves its skeleton and bails out and finds another place to set up shop. But this is a stress response and a rare, crazy thing.

Could the raft actually harm the reef?

It doesn't look like the raft is one massive piece. It looks like a large conglomeration of smaller pieces that happen to have converged and are floating together. So it might break apart. But it could actually abrade the reef.

Is there any concern about carrying in invasive species?

Everything collecting on the raft would be from the Pacific, which is where the reef is. A lot of it will probably be cyanobacteria and algae. I can’t imagine that the living things arriving would be any different than critters being brought there by oceanographic currents anyway.

So it seems unlikely the raft will help the reef—or hurt it, for that matter.

The raft is really fascinating. It’s supercool: there was an underwater volcanic event that released all this material that wound up creating this huge pumice plume that clung together. And yes, all sorts of marine life will colonize that. It would be really interesting to sample it along the way to see the time series: what colonizes it early, what colonizes it later, what colonizes it as it passes certain parts of the ocean. That would give us a better understanding of the ecological relevance of these rafts, too. There are only a handful of papers about them, and the events don't happen very often. The bummer of this story is that it got sensationalized. It got twisted into how this raft is somehow going to save the Great Barrier Reef. Crazy.

It sounds like the most intriguing story is how the raft could redistribute life around the ocean.

Yes, it is moving species around. But humans are moving species around at a much greater rate. Yet in both cases, most of the species don’t take a foothold.

By “humans,” do you mean primarily ship traffic?

A lot of critters travel in ship water—such as ballast water. The most notable ships may be those going through the Panama Canal. I’m not sure this happens with coral much, though. There is a kind of coral called Tubastraea coccineathat is invasive in certain parts of the Caribbean. The hypothesis is that it arrived in ballast water in ships or in ship hulls going through the Panama Canal.

Are the rafts not important, then?

The difference is that the pumice is highly porous, so critters it runs across in the ocean can find a place to grab on, and they will probably live once they attach to it. A coral just drifting around the sea probably wouldn’t last as long. The raft probably increases the longevity and distance of certain taxonomic groups. These really are awesome ecological events. There is a paper from the 1980s that describes one or two species of corals that are thought to have traveled between 20,000 and 40,000 kilometers [12,400 to 24,900 miles] on a raft. That redistributed species throughout different ocean basins.

How is the Great Barrier Reef doing? The terrible, back-to-back bleaching events in 2016 and 2017 took a heavy toll.

We’re seeing some recovery in certain places. The southern Great Barrier Reef was not hit very hard by the bleaching events. But for most of the reef, reproduction of coral has been reduced. When you lose so many corals over a short time period, there are many fewer adults to create babies. The most recent study shows that this “larval recruitment” declined by almost 90 percent after the two events, compared with historical levels. Recovery seems to be happening in isolated places—but at much slower rates, just because you’ve lost a huge portion of your adult population. Australia is putting a lot of focus on restoration to try to assist with that. If you can put more adults back out there, you have a larger population that can help.

Also, a shift seems to be starting, away from the normal taxa you would see on the Great Barrier Reef (such as the branching staghorn and elkhorn species) toward the brooding pocilloporid species—so, less diverse coral communities. Scientists are still monitoring, though; it’s still early. We’re not going to see recovery for a long time.

It’s too bad the pumice raft won’t help.

I think the raft is cool. I don’t want to be negative about it. But I do think the sensationalist idea that this will save the Great Barrier Reef does a disservice to keeping our eye on the prize: understanding that the reason the Great Barrier Reef is in the condition it’s in is because of climate change. We’d be kidding ourselves if we did not acknowledge that elephant in the room. A pumice raft is not going to fix it. People want quick fixes, but they are all Band-Aids. We really have to address climate change.