A cry for help has come from planetary scientists pleading for a Next Mars Orbiter—or NeMO for short. Researchers say the spacecraft fleet currently orbiting the Red Planet are aging and there are no replacements in the works, imperiling future Mars landers, rovers and even possible human missions that will depend on orbiters to talk to Earth. “We are at a turning point in Mars exploration,” says Casey Dreier, director of space policy at The Planetary Society. “NASA declares itself on a ‘Journey to Mars,’ but it can’t even invest in the most basic infrastructure to ensure that goal moves forward.”

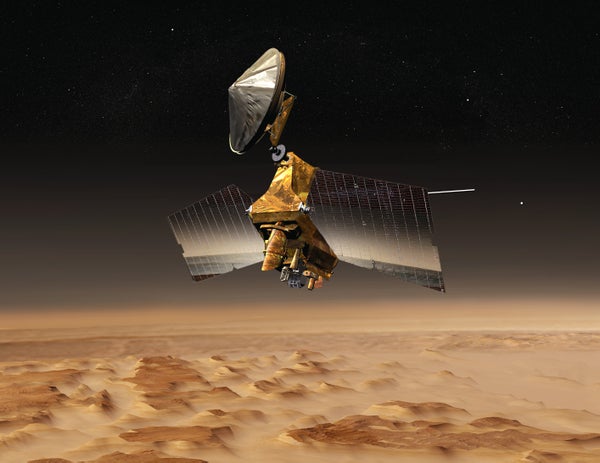

NeMO’s most pressing duty, in many eyes, is to take the baton from veteran NASA spacecraft—the 2001 Mars Odyssey as well as the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), which has been on duty since March 2006—that are at risk of expiring of old age. If they are gone, Earth will be mute to all missions sent to Mars in coming years. And even if they hang on, their technology is becoming outdated. NeMO could offer, for instance, broadband Earth–Mars laser communications—a big plus to handle the projected communications traffic outpouring from the Red Planet down the line.

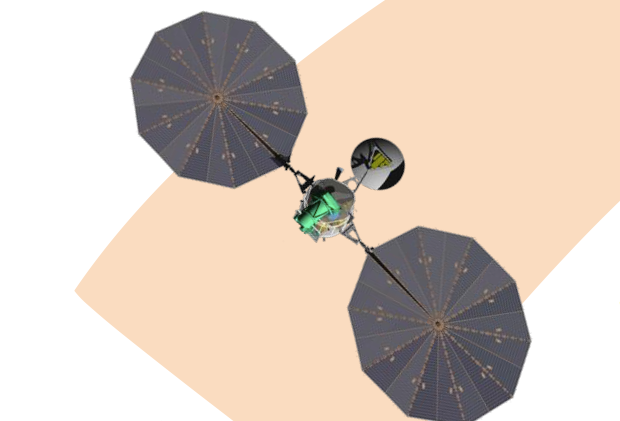

If equipped with radar, NeMO could also serve as a water-witching orbiter. It could scan Mars and map out subsurface pockets of water ice and even assist in X-marking a safe and sound landing zone for astronauts where they can draw on water for oxygen-sustaining needs as well as for concocting rocket fuel. Some scientists also call for NeMO to showcase new solar-electric ion thrusters and advanced solar arrays. With such capacities, the Mars orbiter is ripe for extra assignments such as helping to return precious samples from Mars to Earth or sauntering over and investigating Phobos and Deimos, the planet’s two moons.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

For NASA, there is uncertainty about how NeMO fits into the grand scheme of Mars exploration, and at what cost. Indeed, the proposed 2018 fiscal year space agency budget asks for $19.1 billion for all things civil space. It includes funding for future Mars missions but does not call out NeMO by name. Asked about the situation, Jim Green, director of the Planetary Science Division at NASA Headquarters says only, “We’re continuing to study our options for long-range support of communication for our rovers and landed assets on Mars.”

What is the interplanetary price tag of a new Mars orbiter? It depends. The low-end version would have the spacecraft confined to relaying communications. Things escalate dollar-wise if it will also make science observations and if it comes factory-loaded with new technologies to perform a larger to-do list of tasks. And any funds allocated to NeMO from the NASA budget must contend against other wish list items such as a mission to Jupiter’s moon Europa to search for life, not to mention human exploration of the moon or Mars.

Conceptual sketch of a Next Mars Orbiter (NeMO). Credit: NASA, JPL-Caltech, Charles Whetsel, Robert Lock

Critical Functions

NeMO has three critical functions, says Scott Hubbard of the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics at Stanford University. He was NASA’s first “Mars czar,” a title he earned in restructuring the space agency’s Mars agenda in 2000 in the wake of back-to-back Red Planet mission failures. First of all, he says, it must replace the aging communications infrastructure put into place years ago at Mars. If not, “all the future data and future exploration plans are at significant risk.” Second, a high-resolution imager to replace the MRO’s High-Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) will be crucial to select safe and appealing landing sites for future scientific and human exploration landings.

Finally, another NeMO task that should be included, Hubbard says, is a provision to return samples of Red Planet dirt that could be collected and cached by the so-called Mars 2020 rover set to launch in three years. The engineering solution may be for NeMO to use solar-electric propulsion to turn around and fly back to Earth hauling an entire separate spacecraft that carries the goods from Mars, he says, or it could tote a special-purpose entry vehicle that’s topped off with Mars regolith and rock for drop-off here at home. Others have suggested that returning Mars samples would require an entirely separate spacecraft, or series of spacecraft, on the order of a “flagship mission” costing around $2 billion. “That’s nonsense,” Hubbard says. If requirements are set properly, and the science community and NASA centers engaged in the effort restrain their appetites, Mars sample return can be affordable, he concludes.

Yet with all these possible features and functions, some experts say NeMO is at risk of becoming a “Christmas tree” spacecraft. That is, a mission that is arguably weighed down with too many ornaments and limping limbs while sucking up more and more development dollars.

Concept Studies

NASA has already made some progress toward NeMO. Back in April 2016 the agency requested ideas from U.S. industry about a new Mars orbiter for potential launch in the 2020s. The space agency wanted that spacecraft to provide advanced communications and imaging as well as robotic science exploration in support of NASA’s plans to send astronauts to the vicinity of the Red Planet or its moons sometime during the 2030s.

Later in 2016 NASA picked five U.S. aerospace firms to carry out concept studies for a prospective Mars orbiter mission. Those contract winners—The Boeing Co.; Lockheed Martin Space Systems; Northrop Grumman Aerospace Systems; Orbital ATK; and Space Systems/Loral—took four months to appraise the need for Mars telecommunications and global high-resolution imaging as well as assess possible added scientific instruments, optical communications and the use of solar-electric propulsion. But NASA has not yet awarded a contract to actually move forward with any of these concepts. “I think there’s broad consensus that something is needed,” says Guy Beutelschies, director of deep-space exploration for Lockheed Martin. “But the mechanics of getting that into the NASA budget, funded and moving forward into a real procurement are unclear.”

Yet the space agency is running out of time. The soonest a mission could be ready is probably 2022, and a decision to target that date would need to come soon. “If they want to do a Mars 2022 orbiter…, it’s going to take about four years or so, specifically if they want to inject a lot of new technology,” he says. The orbits of Earth and Mars align every two years, providing a biennial opportunity to launch spacecraft to the Red Planet. “The worry is that if they don’t have something out this year, then they may have to slip it to the 2024 opportunity,” Beutelschies notes.

NASA’s Mars 2020 rover is slated to collect core samples for a possible later spacecraft mission to haul those specimens back to Earth for intensive analysis. Credit: NASA, JPL-Caltech

Shallow Ice

If NASA is serious about human exploration of Mars, then science measurements from a NeMO are essential, says Alfred McEwen, director of the Planetary Image Research Lab at the University of Arizona in Tucson and principal investigator of MRO’s HiRISE. NeMO could find resources like shallow ice at low latitudes, he suggests, and could study whether there are special regions of Mars astronauts should avoid contaminating such as locations with recurring slope lineae. Those are narrow, dark-toned streaks that go down steep Martian slopes, which could be water tracks of salty brines, and potentially home to Martian life.

Hurling humans to Mars means cutting through a thicket of questions and, in turn, that means more reconnaissance, says Rick Davis, assistant director for science and exploration in NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. Having NeMO outfitted with powerful synthetic aperture radar would enable it to spot ice at depth and help plan tapping that resource for use by future Mars crews, he explains. “What we don’t know is where the water is and whether it’s in veins or fields,” Davis says. “There are big knowledge gaps, and you need more resolution than what we’ve had to date.”

Troubling Path of Decline

The lack of plans for NeMO is just one of a number of problems threatening NASA’s desire to dispatch humans to Mars. The Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel (ASAP), a committee that reports to NASA and Congress, noted in its 2016 annual report that the space agency’s humans-to-Mars plans are in yellow condition—meaning the panel is not confident that important issues or concerns are being addressed adequately by NASA. The safety group recommended to the agency the establishment of a Mars Mission Program Office and/or designation of a “Mars czar” that could facilitate needed studies and make sure limited funds are being spent on the appropriate technical challenges. “NASA has made some progress in defining the journey to Mars, but in the opinion of the panel, current plans lack substantive risk reduction, technology maturation and advanced systems development to achieve the stated goals,” the ASAP report explains. Moreover, the group said establishing a Mars Program Office could facilitate these efforts.

“We are essentially riding on the investments made in the previous decade,” Dreier says. Earlier this month the public space advocacy group issued a review of NASA’s Mars program, stressing that “not all is well with the future of Mars exploration.” Furthermore, the space advocacy group claimed the space agency’s robotic program for the Red Planet is on a “troubling path of decline…and decisions must be made now in order to stop it.” Dreier is co-author of the report, titled Mars in Retrograde: A Pathway to Restoring NASA’s Mars Exploration Program. Among its recommendations, the document suggests NASA should immediately commit to a Mars telecommunications and high-resolution imaging orbiter to replace rapidly aging assets currently in orbit. “You would think that making the case for a new orbiter would be easy,” Dreier says, “but so far NASA has been unable or unwilling to commit to starting one for launch in the early 2020s.”

All in all, Dreier says the big takeaway about Mars and the space agency, in his view, is clear: NASA built an extraordinary program of Mars exploration in the first decade of this century. The level of investment shrank in the 2010’s to the point where there is only a single mission in development as part of the Mars program: the Mars 2020 rover. That wheeled robot is scripted to fetch samples to be returned to Earth by a mission that has yet to be blueprinted or even approved, he notes. “Though its science instruments will generate more data than any previous surface mission, [the Mars 2020 rover] will depend on an orbital relay network that will be nearly 20 years old to return this invaluable data,” Dreier says. In regards to NeMO, as Dreier sees it, “we can fix this, but we need to start this mission now. We roll the dice otherwise.”