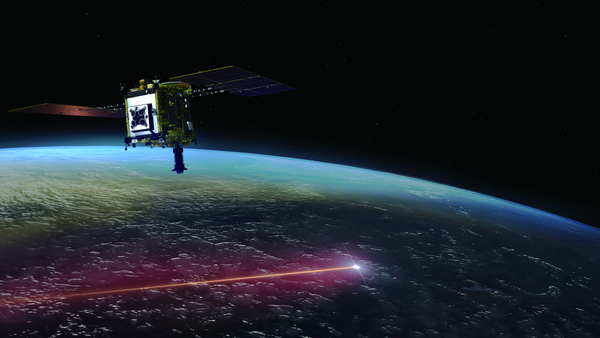

Japan’s Hayabusa2 spacecraft is nearly home. Having collected samples from the asteroid Ryugu last year, the spacecraft is just months away from returning them to Earth. The samples contain material that likely dates back to the dawn of the solar system, 4.6 billion years ago. They could provide fresh insights into how celestial bodies came to be and even how life on Earth began. But before all that, there is the small matter of getting Hayabusa2’s precious cargo down from the harsh vacuum of space and safely into scientists’ hands.

On July 14 the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), in partnership with the Australian Space Agency, announced the landing date for the samples: December 6, 2020. JAXA’s landing site for the mission is a 122,000-square-kilometer region of South Australian outback known as the Woomera Range Complex.“Woomera is a very remote area,” says Karl Rodrigues, acting deputy director of theAustralian Space Agency. “It makes it ideal for the safe management and landing of this particular craft and capsule.”

Hayabusa2’s predecessor, Hayabusa, also used the Woomera landing site when it returned a capsule containing about a millionth of a gram of dust from the asteroid Itokawa in 2010. That mission had been planned to retrieve far more, but it was hindered by multiple mishaps in deep space. Hayabusa2’s haul from Ryugu should be larger—up to a gram of material. JAXA is not alone in struggling with sample-return efforts: in 2004 NASA also experienced some issues with its Genesis solar-particle-retrieval capsule, which slammed into the Utah desert after a parachute failed to deploy. The U.S. space agency’s Stardust capsule—which carried samples of Comet Wild 2’s tail—fared better when it landed safely in 2006.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Hayabusa2, similar in design to its predecessor, launched in 2014 and arrived at Ryugu in June 2018. It descended to the asteroid’s surface in February 2019, firing a small projectile into the ground and hopefully scooping material up into a container (there is no way to know for sure that the maneuver was successful until the capsule returns to Earth). In April 2019 the spacecraft fired an impactor into Ryugu from a distance, forming a small crater. Then it swooped down again in July 2019 to grab material ejected by the impact. Last November Hayabusa2 finally left its orbit around the asteroid and began its one-year journey home.

When Hayabusa2 flies by Earth in December, it will drop off the sample capsule, which must endure a fiery reentry in our atmosphere before parachuting safely to the ground. The spacecraft will head back into space, on an extended mission to one of two possible additional asteroids. On the ground, a team of about 10 JAXA scientists—few enough that coronavirus restrictions should not hamper the recovery efforts—will await the capsule’s arrival. They will rely on its radio beacon, as well as drone-based reconnaissance, to locate its precise touchdown site. The scientists’ aim will be to find the capsule within 100 hours of landing. “Probably, we can find it more quickly,” says Satoru Nakazawa, the deputy manager on the Hayabusa2 team. Hayabusa’s capsule, for instance, was found within 24 hours. “But in the case of some trouble, it can take more time,” he says.

Once the capsule is found, it will be taken to a nearby building in Woomera called the Quick Look Facility. Most studies of the samples will take place in Japan, at the Extraterrestrial Sample Curation Center (ESCuC) in the city of Sagamihara, near Tokyo. But some preliminary analysis will be conducted in Australia. Gazing through a small hole into the capsule’s two sample containers—one from each landing site on the asteroid—team members will first confirm there are actually some samples to study. They will then siphon any volatile gases, such as water vapor, from the containers to ensure these more delicate components of the samples are not spoiled by exposure to Earth’s atmosphere. “Without opening the container, we can take out any volatiles released inside,” says Shogo Tachibana, who leads Hayabusa2’s sample analysis team. “We will put those volatiles into gas tanks and make a quick analysis.”

Following this early analysis, roughly a day after the capsule’s return to Earth, JAXA will fly the samples to ESCuC. There, in a clean room, the capsule containers will be opened for the first time. A portion of the samples will immediately be set aside and stored for future generations to study, ideally with more advanced equipment than is available today. (Something similar was done with moon samples from the Apollo program, which are still only gradually being opened.) The remainder will be transferred to a chamber filled with pure, inert nitrogen gas. “All the samples will be handled, photographed, weighed, and [we’ll make] nondestructive spectroscopic observations, ready for further analysis,” Tachibana says.

JAXA scientists will have about a year to perform initial studies of the samples (early results from the mission suggest Ryugu, despite being composed of ancient material, may have only formed into its current shape 10 million years ago). After this work, some of the retrieved samples may be sent out to international partners for further examination, depending on how much material is available to distribute. That process will likely entail a deal for a swap with NASA’s own asteroid-sample-retrieval mission, called OSIRIS-REx, which is scheduled to return to Earth from the asteroid Bennu in 2023. “Half a percent of [our] sample will be sent to Japan in exchange for Hayabusa2 samples,” says Jason Dworkin of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, who is project scientist for OSIRIS-REx.

Hayabusa2 will have the first turn in the limelight, however. And if all goes to plan, it could provide a fascinating glimpse into the early solar system—and possibly even our own beginnings here on Earth. Scientists will search its samples for signs of hydrated minerals, organic material and other building blocks of biology. “We’re very interested, fundamentally, in the origin of life,” says planetary scientist Rhian Jones of the University of Manchester in England, who is hoping to study some of Hayabusa2’s primordial souvenirs herself. “Getting samples back from an asteroid like this is a really important part of that.”