A spate of fires in the Amazonian Andes has been lighting up Colombia’s national parks, particularly those that until recently had been controlled by guerrilla fighters. The blazes, scientists have found, appear to be a good indicator of the region’s ongoing forest loss after five decades of warfare.

In late 2016 the government signed a peace agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). A few months later the rebel group disbanded, abandoning the battle camps and handing over thousands of weapons. The deal put an end to the longest-running armed conflict (pdf) in the Western Hemisphere, according to the International Center for Transitional Justice. It also emptied the territories FARC had dominated for so long, including the dense forests that provided cover and refuge against the government forces.

In only one year the power vacuum that followed the guerrilla demobilization translated into a sixfold increase in fires within protected areas, according to a study published Monday in Nature Ecology & Evolution. “Many of those places that [were once] off-limits are opened up again to people who may have been kept out for years,” says Thor Hanson, a conservation biologist and independent consultant who did not take part in the study. The outcome, although severe, was not unforeseen.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

This February 23, 2018, photo shows volunteers from the Colombian Civil Defense, in orange, and staff from the System of National Natural Parks, in blue, trying to put out the flames of a fire that affected more than 1,200 acres in the Sierra de la Macarena National Natural Park. Credit: Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia

When she was a graduate student at Columbia University, Liliana Dávalos published a paper speculating that peace could be worse than war for Colombia’s environment. “Some of the remnant biodiversity-rich forests that have persisted through the war may not survive the kind of exploitation that peace can afford,” she wrote in 2001. “I wish I’d been wrong,” says Dávalos, now an evolutionary biologist at Stony Brook University in New York State and co-author of the new study, which reveals protected areas have become the target of a massive transformation in Colombia.

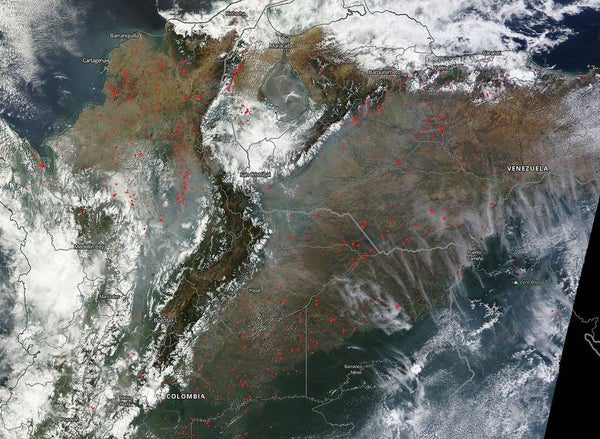

By analyzing images collected by NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites, Dávalos and her team noticed a spike in fire frequency during the dry seasons of 2017 and 2018. Many of those conflagrations occurred in the Amazonian Andes, in protected areas that used to be under strict FARC control. The signal was particularly strong in a corridor of three contiguous parks: Cordillera de los Picachos, Tinigua and Sierra de la Macarena. Within the reserves the researchers also detected a 69 percent jump in deforestation—from about 19,000 acres in 2017 to some 33,000 acres in 2018—following the fires.

Hanson, who has previously reviewed the ecological impacts of warfare, says the trend “is an aberration that cannot be explained by weather patterns. If it was just a difference in weather, you would see the same increase [in fires] across the board,” not only in protected areas.

But other outside experts warn the study should have included more data from the time prior to the peace agreements to present an airtight case. “You can certainly see that there was a substantial change between the years,” says ecologist Mark Cochrane from the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. “However, it is not certain that this is necessarily caused by the peace agreement. It is plausible and even likely to be true, though,” he notes.

Dolors Armenteras, co-author of the study and a landscape ecologist at the National University of Colombia in Bogotá, has spent more than 15 years studying the country’s fire dynamics. She says the findings are unprecedented. “The [fire] signal we capture inside and around protected areas is very clear,” she says, adding, “it got worse” after the conflict ended.

Credit: Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia

Scientists believe newcomers waiting to cash in on newly accessible land, former combatants and others may be using fire to clear the forests. But the Colombian government does not know for sure who is behind the forests’ destruction or what their goals are. José Manuel Ochoa Quintero, a biologist at the Alexander von Humboldt Biological Resources Research Institute in Bogotá, thinks this study should be a “wake-up call” for conservation authorities before it is too late. “The post-conflict is reshaping the country,” says Ochoa Quintero, who was not part of the research group.

Colombia’s minister of Environment and Sustainable Development Luis Gilberto Murillo and others have suggested possible solutions. Former FARC members could become stewards of the jungles they patrolled for so many years. Local populations could benefit from conserving the protected areas if they find sustainable ways to live off the land. And a domestic timber market could force people to pay if they want to chop down the forests.

What is clear, Dávalos says, is that a threat of violence cannot be the only way of keeping her country’s forests safe. “Going back to the way things were before—meaning there was so much armed conflict that a lot of these places couldn’t be accessed by people—is not desirable. And it’s something that none of us are advocating for.”