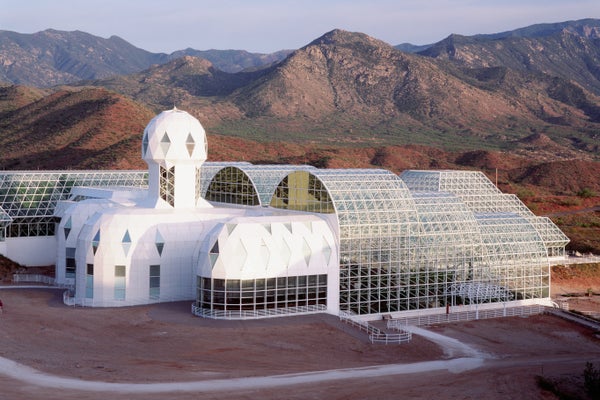

ORACLE, Ariz.—Opening the door to a glass pyramid, a visitor steps from the arid heat of Arizona into a coastal fog desert that stretches toward a savanna. A Lilliputian ocean laps against a rocky shore. A passageway leads to a steamy rain forest where vine-necklaced trees tower 90 feet high. Here in Biosphere 2, the world’s largest controlled environment dedicated to climate research, scientists can tinker with scaled-down ecosystems by switching off sprinklers and cranking up the thermostat to learn about the effects of global warming out in the real world.

The facility has long been shadowed by its ill-fated 1991 maiden mission to establish an analogue of a self-sustaining colony on another planet. But after some retooling and successful, high-profile studies—including one that revealed warming oceans are killing corals—the giant terrarium (led by the University of Arizona since 2011) is finally living up to its potential as a site for novel and risky research.

In its half-acre rain forest, scientists are probing how tropical ecosystems might weather late-21st-century heat and drought. Soon researchers hope to experiment with radical coral reef restoration methods in the enclosure’s million-gallon ocean. And in March 2022 the operation will unveil a Mars analogue that reprises the original founders’ dream of mimicking a plant-filled habitat on a lifeless alien world. Biosphere 2 is effectively like a time machine that can preview a climate-altered Earth “by changing the concentrations of gases in the atmosphere to those that we think are going to exist in the future to see how the planet could fare,” says the facility’s current director Joaquin Ruiz.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Past Struggles

Biosphere 2 launched 30 years ago, on September 26, 1991, when a crew of eight—including a physician, botanist and marine biologist—began a two-year residency inside this 3.14-acre terrarium. The structure, a prototype for an extraterrestrial habitat, was conceived by a counterculture theater troupe that partnered with businesspeople to form a company called Space Biosphere Ventures. It was intended to be a hermetically sealed ecosystem where several biomes, 3,000 species of plants and animals, and a farm would provide the “biospherians” with all the air, water and food they needed. “At the time, a lot of scientists said it literally could not be done, that the whole thing was going to turn into green slime,” says Jane Poynter, one of the original biospherians and founder of spaceflight company Space Perspective.

Biosphere 2 contains a mini ocean next to a savanna and a mangrove forest. Credit: Alamy

The enclosure did not ooze slime. But after a year, the oxygen had dwindled to dangerously low levels, the farm was not producing enough crops—and the crew was suffocating and hangry. To solve the problem, some members of Space Biosphere Ventures’ management team pumped oxygen into the building and used a CO2 “scrubber” without disclosing their actions publicly. When the truth emerged, the mission lost credibility with scientists and was panned by the press. Some still consider this unfair. “It was absurd that the media portrayed it as a failure, because it completely missed the point that it was an experiment,” Poynter says, adding that the goal was to discover what problems arise in a human-made biosphere and to learn from those dilemmas. The failure, say several of Biosphere 2’s current staff, lay in the lack of transparency—not the lack of oxygen.

Scientists did, in fact, learn something important from what went wrong: the soil was too rich in organic matter, and its thriving bacteria gobbled up too much oxygen. At first, the researchers could not track down the excess carbon dioxide those microbes should have released as a byproduct of that oxygen consumption. Eventually they found it had chemically bonded with concrete in the building. “It was a light bulb moment,” says John Adams, Biosphere 2’s current deputy director. “They could trace, molecule by molecule, where [carbon] was going and where it was being stored in ways that they couldn’t outside” in the real world.

When Columbia University took over Biosphere 2 from 1996 to 2003, researchers realized that, inside this controlled mini world, they could tweak the CO2, heat and precipitation to predicted future levels and could measure the effects on varied biomes. “Quite a few people thought that this is an exquisite tool because you have a complicated system that you can completely close and risk damaging and learn how stressed systems behave,” says Klaus Lackner, director of the Center for Negative Carbon Emissions at Arizona State University, who is not affiliated with Biosphere 2. “The challenge is: you have to make sure it’s actually reflecting a real system. I think one can walk that walk, and some of that [research] is being done now.”

Understanding the Future

Christiane Werner, an ecosystem physiologist at Germany’s University of Freiburg, used the facility’s rain forest to investigate how tropical plants and soil share nutrients to protect each other from climate change—and what happens when those support systems fail. Several recent studies have shown that deforestation and climate-related tree death are transforming rain forests such as the Amazon from carbon storage spaces into massive greenhouse gas emitters. Werner’s goal is to find what causes these tipping points. Doing so could help researchers make better climate predictions and develop more effective reforestation techniques.

Werner’s team released traceable forms of carbon and hydrogen into the glass-domed rain forest, then turned off the sprinklers to induce a 9.5-week “drought” and tracked where the elements traveled. “That has never been done before,” she says, “and Biosphere 2 is the one place on Earth where you can do such an experiment because you have a fully grown forest you can manipulate.” In the Amazon, it would of course have been impossible to conjure a two-month dry spell, and the chemical tracers could have escaped anywhere, she notes.

The soon to be published results are being kept under wraps, but Werner says the main takeaway was the diverse ways various plant species coped with the stress. “Because they have different functional responses, it buffers the whole forest,” she explains, adding that biodiversity is therefore key to keeping forests stable in turbulent climatic times.

Other experimental results from Biosphere 2’s rain forest have been heartening. In

a 2020 study published in Nature Plants, Michigan State University ecologist Marielle Smith and her colleagues dialed up the temperature and found that the tropical flora were more resilient to high heat than many had anticipated.

At the facility’s mini ocean, researchers are partnering with microbial sciences company Seed Health to dose corals with probiotics to see if this can deter bleaching (which occurs when heat-stressed corals expel the symbiotic algae that help feed them). The scientists are also developing a program to experiment with “super corals” that are bioengineered to be resistant to heat and acidity. “If you’re in Miami or Hawaii, you can’t get permits to do that research because there’s a fear that genetically modified corals will get into nature,” says Chris Langdon, a University of Miami marine biologist who is on Biosphere 2’s science advisory committee. “With Biosphere 2 being in the middle of the desert, there would be absolutely no risk if anything escaped.”

Langdon is no stranger to Biosphere 2’s ocean. In the 1990s he conducted research there, revealing for the first time that ocean acidification causes corals to dissolve from a lack of calcium. He says the giant tank would also be a good place to test a leading idea to achieve negative carbon emissions: raising the ocean’s pH by adding dissolved rocks, giving the water a greater capacity to pull carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

Not all of Biosphere 2’s projects focus on climate. Its so-called Space Analog for the Moon and Mars (SAM), currently under construction, “is very much, at a scientific level and even a philosophical level, similar to the original Biosphere,” says SAM director Kai Staats. Unlike other space analogues around the world, SAM will be a hermetically sealed habitat. Its primary purpose will be to discover how to transition from mechanical methods of generating breathable air to a self-sustaining system where plants, fungi and people produce a precise balance of oxygen and carbon dioxide.

Visiting researchers will hydroponically grow fruits and vegetables in SAM’s greenhouse, which is painted and tinted to block the sun and mimic the dimmer daylight on Mars. They will also experiment with transforming regolith (crushed rocks that resemble lifeless Martian basalt) into fertile soil. This could have implications for reviving some of Earth’s degraded terrains.

And in light of the precarious status of Earth’s climate, Staats hopes the scientists who live in SAM will experience the kind of epiphany he says was described to him by Linda Leigh, one of the original biospherians. “She said that, in such a closed environment, you can’t help but be aware of every breath you take, every drink of water you consume and every morsel of food you eat because it doesn’t go someplace where you never see it again,” he says. “It comes right back to you.”