Editor’s Note (3/21/22): This article was originally published on March 27, 2019, when Russia’s hypersonic nuclear weapons were still in development. It is being republished because of Russia’s claim, reported this past weekend, that it has used hypersonic missiles for the first time, striking targets in Ukraine with its Kinzhal missiles.

Both the United States and Russia last month pulled out of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF), a Cold War–era pact that prohibited land-based ballistic or cruise missiles with ranges between 311 and 3,420 miles. That agreement limited just one class of weapons, but it is not the only accord poised to end: The much-broader New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) will expire on February 5 next year, unless both parties agree to extend it—which they may not do.

New START limits the number of missiles the U.S. and Russia deploy, with an eye toward reducing the overall number of nuclear weapons in the world. Without it, for the first time since 1972 there would be no limit on how many warheads either nation can build and deploy. As tensions rise, both countries are looking to modernize their nuclear weapons, and Russia in particular is teasing terrifying new missiles that—if they work—could bypass the U.S.’s elaborate system of ground- and satellite-based defenses.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“The Russians really hate missile defense,” says Jeffrey Lewis, a nuclear policy expert and professor at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies in Monterey, Calif. “They really don’t like the possibility that they might be outmatched technologically. So there’s a whole battery of Russian programs—from the doomsday torpedoes, to nuclear-powered cruise missiles, to hypersonic reentry vehicles, to anti-satellite weapons.”

Last year Russian President Vladimir Putin unveiled six new weapons during a governmental address. The most impressive, according to nuclear experts, were the Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle, the nuclear-powered cruise missile Skyfall and the RS-28 Sarmat intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). These three are the crown jewels in Russia’s aggressive new nuclear policy, capable—according to Putin—of circumventing U.S. missile defense systems. Currently, American defenses are designed to knock an incoming nuke out of the air before it can hit its target—but this was already a complicated and difficult task before the development of hypersonics.

Although Russia’s new weapons sound frightening, none has actually been deployed yet. They may be ready in the next year or two, but “none of them are fully operational,” says Philip Coyle, a board member of the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation. Coyle (who has also served as U.S. assistant secretary of defense), explains that some have been tested, but “none of them have been so successful that they can claim to have operational capability.”

But that doesn’t mean Coyle is not worried, especially about hypersonic threats. “Some of those would be impossible for United States missile defense systems [to counter],” he says, “especially the hypersonic air-to-ground-system and the hypersonic glide system, both of which [Putin] said had been successfully tested.” The current crop of weapons that defense experts label as hypersonic reach speeds greater than 3,000 mph.

Inside the Nuclear Arsenal

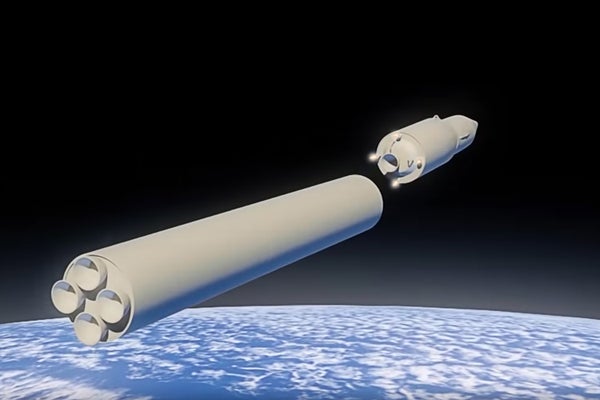

Other countries, including the United States and China, have also tested hypersonic weapons—but it is Russia’s hypersonic glide vehicle, the Avangard, that has garnered the defense community’s most intense attention. Glide vehicles could theoretically combine the maneuverability of a cruise missile with the speed of an ICBM. On a traditional nuclear launch involving an ICBM, a powerful rocket sends the warhead on a trajectory similar to a space launch (long-range ICBMs even go suborbital) before it turns around and plummets to Earth at hypersonic speeds. Glide vehicles like the Avangard would ride an ICBM into the sky, but they would then be released and soar along at the top of the atmosphere—above sensor range—before heading to their targets.

However, not everyone is fretting about high-speed glide vehicles. “I’m not so impressed by those,” Lewis says. He says the vehicles themselves, once released, will no longer be traveling at hypersonic speeds (although other experts disagree with this assessment). “The missile is gliding, so it actually slows down quite a bit and makes a much better target [than traditional ICBMs] for missiles defenses,” Lewis says. The vehicle could supposedly move to evade a defense system, but Lewis remains unconvinced. “It’s great that it can maneuver so that it doesn’t come into the range of missile defenses. But if it does, it’s going to be a much brighter target because it’s moving more slowly and it’ll be superhot,” he says. “The hypersonic gliders people are talking about actually represent slower reentry than what currently exists.”

Instead Lewis worries more about the Skyfall, the nuclear-powered cruise missile carrying a nuclear warhead. “I’m a little bothered by the menagerie of science fiction ideas that the Russians are working on,” he says. “We don’t know much about the technology behind that one (Skyfall), but certainly when the U.S. investigated the idea it was pretty nasty in terms of radiation released just to power it.” According to Putin, the Skyfall is a superpowered Tomahawk cruise missile launched via ground or air. The best Tomahawks can travel 1,550 miles—but with a nuclear reactor powering it, the Skyfall effectively has an unlimited range. Russian military sources reported the country had successfully tested the cruise missile in January 2019; however, U.S. intelligence suggests that it has yet to demonstrate a range greater than 22 miles, and may not reach its full potential for another 10 years.

Still, a radiation-spewing cruise missile with unlimited range is not Russia’s only frightening new weapon. It is also testing the RS-28 Sarmat, a liquid-fueled ICBM designed to brute-force its way through U.S. missile defense systems. The missile is fast, huge—119 feet tall with a weight of more than 220 tons—and full of weapons: It carries a 10-ton payload, big enough to include 24 separate nuclear-tipped Avangard hypersonic glide vehicles.

And the Sarmat is dangerous for reasons beyond its size. According to Coyle it also has a shorter-than-usual boost phase (the period of an ICBM’s launch when it is rocketing into the atmosphere), which gives U.S. missile defenses less time to shoot it down. If a brief launch window is not enough to protect the missile, Coyle says, “[Putin] also said that Sarmat would carry countermeasures designed to confuse U.S. anti-missiles systems.”

Response Time

The Sarmat’s short boost phase exemplifies what really makes these missiles so terrifying: time. Nuclear warheads are always dangerous, but the U.S. has long relied on its ability to create lead time between launch, detection and response. Essentially, the longer the commander-in-chief has to decide how to react to the news of an ICBM launch, the better. The abilities of these new weapons—short boost times, hypersonic speeds and unlimited range—all eat into those precious minutes. “It’s going to tighten the noose around our necks,” Lewis says. “These systems add complexity and reduce decision time. That’s the kind of change that can really threaten stability.”

Meanwhile, the most recent U.S. Nuclear Posture Review and Missile Defense Review promised to develop America’s own hypersonic weapons. The reviews also teased the creation of new sensors, floated the idea of turning the F-35—the new U.S. fighter jet—into an ICBM killer, and suggested developing space-based sensors to augment American missile defense systems. But both reviews were long on theory and short on details. In particular, Coyle says, “The Missile Defense Review is unclear about what it is we would deploy in space.”

As for shoring up U.S. defenses, the Pentagon is trying to develop hypersonic counter-measures. At the moment, the country’s missile defense shield includes a mix of 44 ground-based interceptors; Terminal High Altitude Area Defense systems deployed in Guam, the United Arab Emirates, Israel and South Korea; and Aegis missile defense systems on U.S. Navy ships around the globe. New plans include everything from thousands of interceptors orbiting the Earth to lasers fired from satellites, and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is actively searching for a “glide-breaker,” a way to fight against hypersonic glide vehicles like the Avangard.

However, these protections are still theoretical. At the moment, no one has a concrete solution to the threat—and Russia continues to build and test new and potentially devastating nuclear weapons.