Your face is the future of smartphone security. Apple made that clear last week when it unveiled the pricey iPhone X, which trades in the familiar home button and TouchID fingerprint scanner for a new camera system that unlocks the device using facial recognition.

The company has repeatedly proved its ability to push emerging technology into the mainstream—but with FaceID, Apple claims to have conquered many of the challenges that have prevented the widespread use of facial biometrics. But a number of computer-vision researchers say they are skeptical that a smartphone-based system like FaceID can account for things like variable lighting conditions or subtle changes in a person’s appearance to create a secure-yet-practical way to unlock a phone a dozen or more times a day.

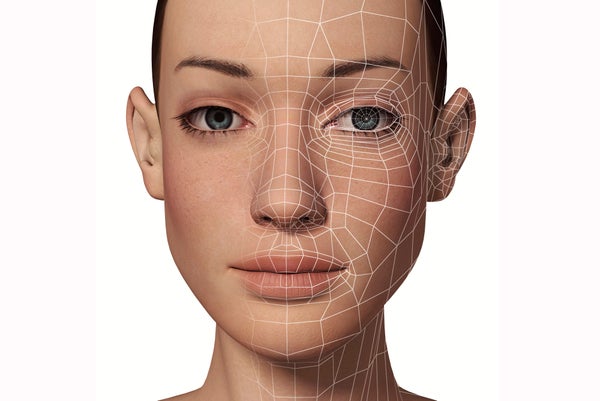

Apple’s new technology does sound promising. The company says FaceID creates a “precise depth map” of one’s visage by projecting more than 30,000 infrared dots against a person’s face, then using the phone’s infrared TrueDepth camera and high-power microchip to collect and analyze the results. Users are also asked to turn their head as they scan so the phone's machine-learning algorithm can measure the face from several angles and create a more detailed 3-D map of their features. Once the map is created and stored, the iPhone X uses infrared light to help FaceID scan a person’s face even in the dark. Meanwhile, machine-learning algorithms running on the phone’s new A11 Bionic chip keep track of changes in a person’s appearance—including glasses, facial hair and hats—so the smartphone’s accuracy improves over time.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Despite advances in facial recognition in recent years—law enforcement agencies including the FBI use it to check suspects against data bases of mug shots—it remains unclear whether FaceID will work in a variety of conditions while also keeping the iPhone X secure. Hackers, for example, quickly found a way to bypass the Samsung Galaxy S8's facial-recognition scanner when it was introduced in March: They tricked the device by simply showing it a photo of the user. FaceID’s use of 3-D facial maps could address that problem. But historically it has been a big challenge for such a system to recognize faces under different lighting conditions and from a variety of angles, says Jonathon Phillips, an electronics engineer at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, which develops standards for the technology industry.

At the September 12 iPhone X rollout, Philip Schiller, Apple’s senior vice president of worldwide marketing, acknowledged some of those challenges. He pointed out that FaceID will not unlock the phone if the user’s eyes are closed or are not lined up properly with the camera. Such limitations are significant, given that iPhone X customers will use FaceID to access their Apple Pay app, which is used to make purchases and linked directly to a person’s bank account.

Apple showed off FaceID last week under relatively controlled conditions, says Arun Ross, a professor of computer science and engineering at Michigan State University. “Clearly the demo was very interesting,” he says. “But at the same time some extraordinary claims were made." Apple’s Schiller said, for example, that the chance a random person’s face could unlock someone else’s iPhone X was one in a million—much more secure than TouchID, which relies on fingerprint biometrics. Ross says, however, that it is not clear how often FaceID fails to recognize its owner. When contacted, Apple declined to elaborate on Schiller’s comments.

Most facial-recognition systems rely on an algorithm that compares certain points on a face against those same points on a stored image, and then generates a score based on similarity, says Anil Jain, also a Michigan State computer science professor. A system will first check basic parameters that most faces have, such as two eyes and a nose. It will then take more precise measurements, such as the angle between the edge of the mouth and the nose, for added security.

That unique data can, however, also be a liability for biometric security. “Like all biometrics, FaceID will have a problem with revocation,” says Vitaly Shmatikov, a computer science professor at Cornell Tech. “If a password is compromised, it can be changed—but a face cannot be changed.” Apple touts its ability to secure data on its iPhones, which do not share biometric information with the company’s servers. Still, Ross says, hackers always seem to find a way around even the tightest security.