After two days of speculation and investigation, the fate of the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Schiaparelli lander is now clear. New images from NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) reveal that the kiddie-pool-sized spacecraft—meant to softly touch down and then send signals home on October 19—was instead destroyed when it crashed into the surface.

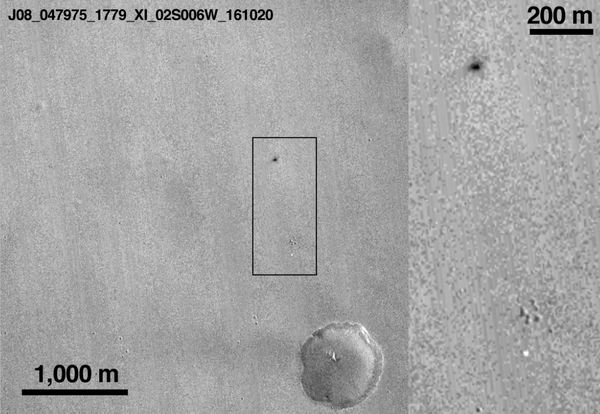

Passing over Schiaparelli’s intended landing site in Mars’s Meridiani Planum on October 20, one of the orbiter’s cameras spied two new features that did not appear in earlier images taken in May. Although the images are relatively low-resolution at just 6 meters per pixel, they reveal a bright object thought to be Schiaparelli’s parachute, as well as a 15-by-40-meter dark patch roughly one kilometer to the north of the parachute. ESA investigators now believe the impact and possible explosion of Schiaparelli produced the dark patch, which is five and half kilometers west of the bullseye touchdown they had hoped for.

Initial analysis of Schiaparelli’s radio signals during its atmospheric entry and descent suggested that the lander successfully deployed its parachute as planned, but the lander’s signal was unexpectedly lost a minute before its scheduled touchdown. Closer examinations of the lander’s transmitted telemetry then revealed that the ejection of the parachute and a heat shield occurred earlier than expected, followed by a too-brief firing of rocket thrusters meant to slow the spacecraft’s descent. MRO’s new images support this interpretation and strongly suggest that the sizable dark patch is a crater produced when Schiaparelli struck the surface at greater than 300 kilometers per hour after a two-to-four-kilometer free fall. Because the lander’s thrusters were likely shut off prematurely, Schiaparelli’s full fuel tanks may have exploded upon impact.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Investigators are still working to pin down the exact cause of Schiaparelli’s crash, and will be aided by additional details revealed in higher-resolution images scheduled to be gathered next week by MRO. As part of the joint European-Russian ExoMars mission, the lander was meant to demonstrate technology for safely deploying large payloads to the Martian surface—particularly an ExoMars rover planned to land on the Red Planet in 2021. Instead it has become the second high-profile failure for European efforts to land on Mars, following the loss of the United Kingdom’s Beagle 2 lander in 2003. To date more than half of all landing attempts on Mars have failed, in part due to the complex procedures required to successfully decelerate through the planet’s thin atmosphere.

Despite the disappointments, there is a silver lining to this latest dark patch on Mars: The ExoMars program’s other main component, a satellite called the Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) that served as Schiaparelli’s mother ship, successfully entered Mars’s orbit after deploying the lander. After a calibration period, TGO will adjust its orbit in 2017 to begin its science mission, seeking signs of geological and even biological activity upon Mars.