On his way from Princeton University to the New Jersey state capitol building in Trenton a few weeks ago, Andrew Zwicker was noticeably amped. Zwicker is the head of scientific education at the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, but he was en route to his other job: state lawmaker. He was excited because he was about to make a presentation about policy using a toy-size plastic car. “I can’t imagine any lawmaker has ever done this before,” he says.

The New Jersey Legislature’s Science, Technology and Innovation Committee was holding a hearing about fuel-cell technology, and Zwicker is committee chair. Once in the hearing room, he pulled out his model automobile, which, equipped with a water tank and set of wires, runs on hydrogen. Zwicker, the only PhD scientist in the legislature, dove into an explanation about splitting water molecules to produce energy capable of powering a vehicle, and then he let the model zoom across a desk. Later he posted a video of the demo online with the hashtag #TodayWasAGoodDayForScience.

On the verge of Election Day in the U.S. a political movement focused on getting scientists into public office is hoping that results at the polls will lead to more scenes like this one at state houses, city councils and school boards across the country, not just at a federal level. At least 70 scientist–candidates launched bids for office at the state and local level this election cycle, most of them first-time campaigners and part of a record wave of scientists bucking a long-established penchant to avoid the political arena. Organizers hope this will become a deep bench of up-and-coming policy makers with science and technology backgrounds whomight contest for higher office in years to come. Or many may stay local, because those jobs are usually part-time and allow researchers to maintain careers that were their first passion.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“I’ve had conversations with scientists from all over the country who call or write and ask, ‘How did you do it?’” says Zwicker, who was reelected last year. “We’re at a critical stage, and I have no doubt we’re going to see more and more scientists running for public office.” The surge is rooted deeper than a reaction to the Trump administration’s anti-science policies that began in 2017. It is a longer-term response to years of contempt for facts and evidence-based decisions on Capitol Hill and in state houses of government.

Running for Congress, however, requires a deep-pocketed network and the backing of established political machinery—both qualities most scientists aspiring to be politicians tend to lack at the start. That is why a sustainable movement will require building from the ground up, says U.S. Rep. Bill Foster, a Democrat from Illinois and a physicist. “There have been some great candidates emerging recently,” he says. “The main effect of what’s happening now may show up in five or 15 years when a lot of the people who have won at the local level and the state level decide to run at the congressional and Senate level.”

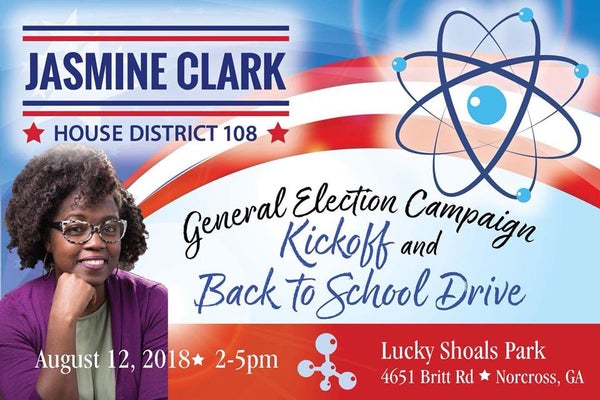

For Jasmine Clark, a microbiologist and lecturer at Emory Universitycompeting for a state house seat in a district about 30 minutes northeast of Atlanta, the decision to run for office was not difficult. But she says there has been a steep learning curve, including figuring out how to craft a message to sell herself to voters. On the campaign trail, though her flyers include a drawing of an atom, she says some people “could care less that I’m a scientist, so most of the time I don’t harp too much on the science part. But when I say things like we need to get back to facts, they all agree with that.”

Clark, a Democrat, ran unopposed in the primary but is now facing an entrenched incumbent with more money and name recognition, a prospect that makes her an underdog in the general election. “To me, this almost feels like a trial run or practice,” she says. “But if I don’t win I know what to do better next time.”

The microbiologist is one of roughly 70 state and local STEM candidates endorsed by 314 Action, a nonprofit and political advocacy group named after the first three digits of Pi. With a war chest of several million dollars, the group is spending its money to train, recruit and support scientists, doctors, engineers and techies. Although most of 314 Action’s money this cycle will go toward a field of endorsed federal candidates, in the future the group wants to put more cash into local races “where a lot of the action on climate, education and health care issues are going to come from,” saysShaughnessyNaughton, 314 Action’s founder and a former breast cancer researcher.

Naughton says 314 Action has heard from about 7,000 people with STEM backgrounds interested in running for office. But “to run for Congress, that’s a full-time job,” she says, speaking from personal experience: She tried it herself, twice, and lost both times. But local races “are much more manageable races in terms of the scope. This is that first step to show you can bring people onboard with you,” she notes.

To reach those people, hobnobbing and working a crowd are musts, and not all scientists do those things well, says Valerie Horsley, a molecular biologist at Yale University, who ran unsuccessfully for state senate in Connecticut earlier thisyear. “I had people tell me ‘you have to go into the room and start shaking hands.’ That was terrifying. Scientists tend to be hunkered in their own world,”she says. “There are skills like that you have to gain to be on the same playing field as some of the other people that are running.”

Horsley adds she is not ruling out another state or local campaign, but running for Congress is not in her future. Federal lawmakers do not hold outside jobs when in office, and for the biologist that is a big problem. “There’s still some things I would still like to do in the scientific world,” she says.

Needing to choose between a career in science and a full-time gig in public service is one of the main reasons more STEM candidates do not run for elected office, says Kevork Abazajian, an astrophysicist and director of the Center for Cosmology at the University of California, Irvine. He is running for an at-large seat on the Irvine City Council, and says that splitting his time between university duties and voter canvassing and fundraising events is currently manageable. But it would be different if he were vying for higher office. “It is more of a challenge for scientists to put off their profession to run,” he says. “One way to try it out is at the municipal level and see what it’s like to run and serve. If it bodes well, they can go on to the state legislature or beyond.”