When Ryan Darby was a neurology resident, he was familiar with something called alien limb syndrome, but that did not make his patients’ behavior any less puzzling. Individuals with this condition report that one of their extremities—often a hand—seems to act of its own volition. It might touch and grab things or even unbutton a shirt the other hand is buttoning up. Patients are unable to control the rebellious hand short of grabbing or even sitting on it. They seem to have lost agency—that unmistakable feeling of ownership of one’s actions and an important component of free will. “It was one of those symptoms that really questioned the mind and how it brings about some of those bigger concepts,” says Darby, now an assistant professor of neurology at Vanderbilt University.

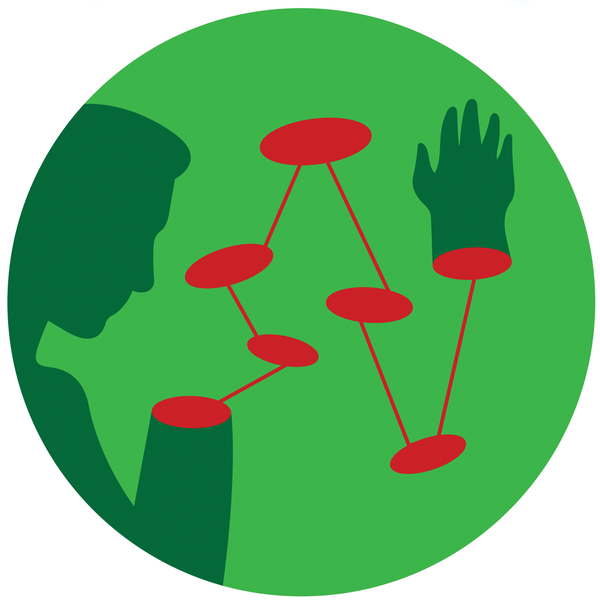

Alien limb syndrome can arise after a stroke causes a lesion in the brain. But even though patients who have it report the same eccentric symptoms, their lesions do not occur in the same place. “Could the reason be that the lesions were just in different parts of the same brain network?” Darby wondered. To find out, he and his colleagues compiled findings from brain-imaging studies of people with the syndrome. They also looked into akinetic mutism—a condition that leaves patients with no desire to move or speak, despite having no physical impediment. Using a new technique, the researchers compared lesion locations against a template of brain networks—that is, groups of regions that often activate in tandem.

Lesions associated with alien limb syndrome all mapped onto a network of areas connecting to the precuneus, a region previously linked to self-awareness and agency. In patients with akinetic mutism, the lesions were part of another network centered on the anterior cingulate cortex, which is thought to be involved in voluntary actions. These two networks also include brain regions, which, when stimulated by electrodes in previous studies, altered subjects’ perceptions of free will, the team reported in October in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The study suggests at least some components of free will—volition and agency for movements—are not localized in any one brain area but instead rely on a network of regions. The perception of will may break down with disruption to any part of that network.

“This is a creative way of using data that’s been sitting around for decades and reconceptualizing it to learn something actually new and make sense of things that didn’t make sense before,” says Amit Etkin, an associate professor of psychiatry at Stanford University, who was not involved in the work. Studies of many other brain conditions could benefit from taking such an approach, he adds.