Editor’s Note (3/20/18): This article is being resurfaced following the death of Sudan, the world’s last male northern white rhino. Only two females remain, pushing the subspecies closer to extinction.

The brazen slaying and dehorning of an endangered white rhino in a wildlife preserve near Paris last month spurred widespread outrage. Mainstream media coverage blamed its usual suspects: Asian men who supposedly buy rhino horn as a crude form of Viagra. But this prurient tidbit overlooks the main factors driving the illegal rhino horn trade—and may even be reinforcing false beliefs about the substance’s powers.

The reality behind the demand is far more complex. Historically rhino populations were decimated by uncontrolled trophy hunting during the European colonial era. These days the main threat to the surviving rhinos comes from the illegal rhino horn trade between Africa and Asia. Certain buyers in Vietnam and China—the largest and second-largest black market destinations respectively—covet rhino horn products for different reasons. Some purchase horn chunks or powder for traditional medicinal purposes, to ingest or to give others as an impressive gift. Wealthy buyers bid for antique rhino horn carvings such as cups or figurines to display or as investments. A modern market for rhino horn necklaces, bracelets and beads has also sprung up.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Most of the desire for rhino horn seems unrelated to any wish for a raging hard-on, experts say. There is one group of buyers in Vietnam that may partially reflect the stereotype of horny Asians seeking a rhino horn fix. A 2012 report by TRAFFIC International, the World Wildlife Fund's trade monitoring program, described how wealthy Vietnamese and Asian expatriate business elites in Vietnam would “routinely mix rhino horn powder with water or alcohol as a general health and hangover-curing tonic”—an extravagant version of a detox routine. That group also included some men who also apparently believed rhino horn could cure impotence and enhance sexual performance.

This example stands out because it is rare, however. Overall, conservationists say there is no sweeping aphrodisiac craze driving lust for rhino horn. “I would never say that (aphrodisiac) is never a use, because I’m sure people buy into the myth,” says Leigh Henry, senior policy advisor on species conservation and advocacy at the WWF. "But it’s not the widespread demand driving the rhino horn trade.”

The Vietnamese black market exemplifies how “urban myth and dubious hype” can encourage demand for rhino horn products—as both medicinal and status-boosting luxury products—the TRAFFIC report says. Black market dealers have also pushed the idea—supposedly sparked by local media gossip—that rhino horn can cure cancer and other life-threatening diseases. Popular Vietnamese Web sites mix unproved medical claims with luxury sales pitches. Slogans compare rhino horn with “a luxury car,” tout its ability to “improve concentration and cure hangovers,” and trumpet “rhino horn with wine is the alcoholic drink of millionaires.”

The TRAFFIC report even implies the Vietnamese buyers who believe in rhino horn’s aphrodisiac powers may have picked up on a media obsession with the idea. Other conservationists have also criticized media outlets for incorrectly tying the aphrodisiac issue so exclusively to Asian traditional medicine or folk therapies. “Use of rhino horn as an aphrodisiac in Asian traditional medicine has long been debunked as a denigrating, unjust characterization of the trade by Western media. But such usage is now, rather incredibly, being documented in Vietnam as the media myth turns full circle," according to the TRAFFIC report.

To be clear, rhino horn has historically been used as a traditional medicinal ingredient in countries such as China and Vietnam. But experts say neither Chinese nor Vietnamese traditional medicine ever viewed rhino horn as an aphrodisiac to boost flagging libidos. Eric Dinerstein, who served as the chief scientist at the WWF for 25 years, summed up the issue in his 2003 book, The Return of the Unicorns: The Natural History and Conservation of the Greater One-Horned Rhinoceros. “In fact, traditional Chinese medicine never has used rhinoceros horn as an aphrodisiac: This is a myth of the Western media and in some parts of Asia is viewed as a kind of anti-Chinese hysteria.”

Just a small percentage of Vietnamese people use rhino horn for any purpose at all, says Michele Thompson, a professor of Southeast Asian history at Southern Connecticut State University who authored the 2015 book, Vietnamese Traditional Medicine: A Social History. Based on her observations, many Vietnamese have heard of the aphrodisiac myth mainly because of the extravagant “fad use of rhino horn” among certain business elites. “This doesn't mean they believe that rhino horn really works as an aphrodisiac; it just means they know that there are people who will spend a lot of money for it,” Thompson says. “In general, Vietnamese traditional medicine does not encourage the use of anything as an aphrodisiac.”

Historically, traditional Chinese medicine has mixed rhino horn with other natural ingredients for treating fever or relieving the symptoms of arthritis and gout. The list of historical uses also includes: headaches, hallucinations, high blood pressure, typhoid, snakebite, food poisoning and even possession by spirits. “Every historical documented use of rhino horn in traditional Chinese medicine was for treating conditions such as fever and infection," says Lixin Huang, president of the American College of Traditional Chinese Medicine. “It was never used for improving male sexual function or for curing cancer.”

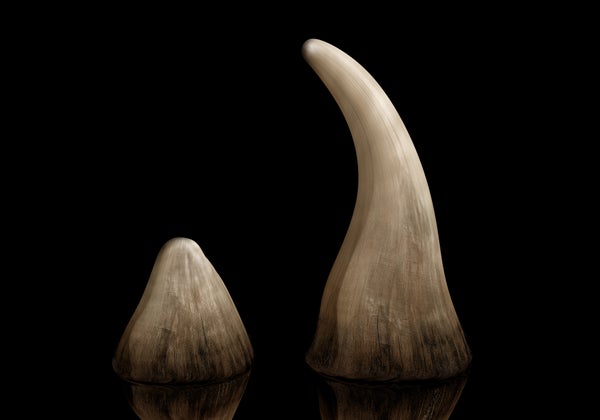

Unsurprisingly, there is no scientific evidence to support the idea of rhino horn having aphrodisiac powers. Rhino horn is primarily made of keratin, the protein that also makes up hair and nails. Raj Amin, an ecologist at the Zoological Society of London who studied the biochemical signature of rhino horn, commented in a 2010 episode of the PBS program Nature that you might as well chew your own fingernails for equivalent medicinal value.

The few medical studies of rhino horn focused on its possible value in treating fever—one of the more common medicinal uses in Vietnam and China. A 1983 pharmacological study by researchers at the Switzerland-based health care company Hoffman–La Roche showed no evidence of such medicinal value. Hong Kong researchers in 1990 published a pair of studies that suggested some fever-reducing value in mice at fairly high doses—but also concluded water buffalo horn worked just as well.

Conservationists have begun identifying distinct groups of rhino horn buyers to better understand what drives demand. The business elites who purchase the product as a luxury health tonic and status symbol “probably account for the greatest volume of rhino horn used in Vietnam today,” according to the 2012 TRAFFIC report. A separate Vietnamese group reportedly includes middle- and upper-class mothers who purchase rhino horn as a traditional treatment for fevers.

A 2015 report lead by Alexandra Kennaugh, a conservation researcher and Illegal Wildlife Trade programme officer for the Oak Foundation, also found two distinct markets for rhino horn in China: a luxury market and a traditional medicine market. The report's survey of more than 2,000 people across five Chinese cities found that those who valued rhino horn as medicine—mostly to relieve fevers or pain—were less willing to pay for it as the price rose. By comparison, those who valued rhino horn as a rare luxury good were still willing to pay through the nose for rhino horn beyond a certain price threshold.

Aphrodisiac usage of rhino horn barely rated a mention in the 2015 report. When asked about preferences for using Chinese, Western or some combination of medicines, a very small percentage of Chinese respondents said they knew friends who had treated erectile dysfunction with rhino horn—but none actually named erectile dysfunction as a condition rhino horn could treat. Erectile dysfunction ranked second to last among “common conditions treated by rhino horn” as reported by respondents. “To be honest, I think that any discussion of rhino horn as an aphrodisiac or for use against erectile dysfunction is a little irresponsible,” Kennaugh says. “It was never prescribed for that in traditional Chinese medicine.”

The nature of the black market makes it tough to gauge whether the traditional medicine or luxury goods market is “in the driver's seat” when it comes to demand for rhino horn, Kennaugh says, adding “most experts” she knows agree the luxury good market is likely the place that will experience growth regardless of the price of rhino horn—or the size of global rhino populations.

A 2016 study by U.S. and Chinese researchers focused on a specific segment of the luxury market. They examined the “art and antiquities” segment among Chinese buyers who purchased carved drinking cups, sculptures and other items made from rhino horn. The study showed the volume of rhino horns auctioned via legal loopholes in China between 2000 and 2011— before Chinese authorities began strictly regulating such auctions—had a significant correlation with the rate of annual rhino poaching in South Africa. Thus the “art and antiquities” market for rhino horn should not be overlooked in trying to reduce demand, says Gao Yufang , a Chinese conservationist and Ph.D. student in conservation and anthropology at Yale University, and lead author of the study. His research published in Biological Conservation also specifically indicted Western media by comparing international (English-speaking) and Chinese coverage from 2000 to 2014. International media emphasized rhino horn’s supposed medical value, he found, whereas Chinese media usually focused on the economic or artistic value of rhino horn carvings. “The supposed aphrodisiac usage of rhino horn is a misperception,” he says.

Still, Gao acknowledged ordinary people's lingering beliefs regarding the traditional medicine value remain a long-term challenge. “This belief in rhino horn’s medicinal properties is so ingrained and widespread that it makes rhino horn trade a much more difficult issue to address when compared to the trade in elephant ivory, which is predominantly used as a carving material,” he says.

On the bright side, traditional Chinese medicine experts have increasingly joined the fight to reduce the demand for rhino horn. When China officially banned the international trade in 1993, it followed up by removing rhino horn as a medical ingredient in traditional Chinese medicine's pharmacopeia and curriculum. Practitioners promoted alternative ingredients such as water buffalo horn and herbal substitutes.

American College of Traditional Chinese Medicine’s Huang has spearheaded conservation awareness campaigns among traditional Chinese medicine practitioners and customers in both the U.S. and China. But she acknowledges the challenges of convincing some customers that the historical use of rhino horn need no longer apply.

“Traditional Chinese medicine has a history of 3,000 years and we have been educating the public for less than 30 years,” Huang notes. “Therefore this is an ongoing education.”