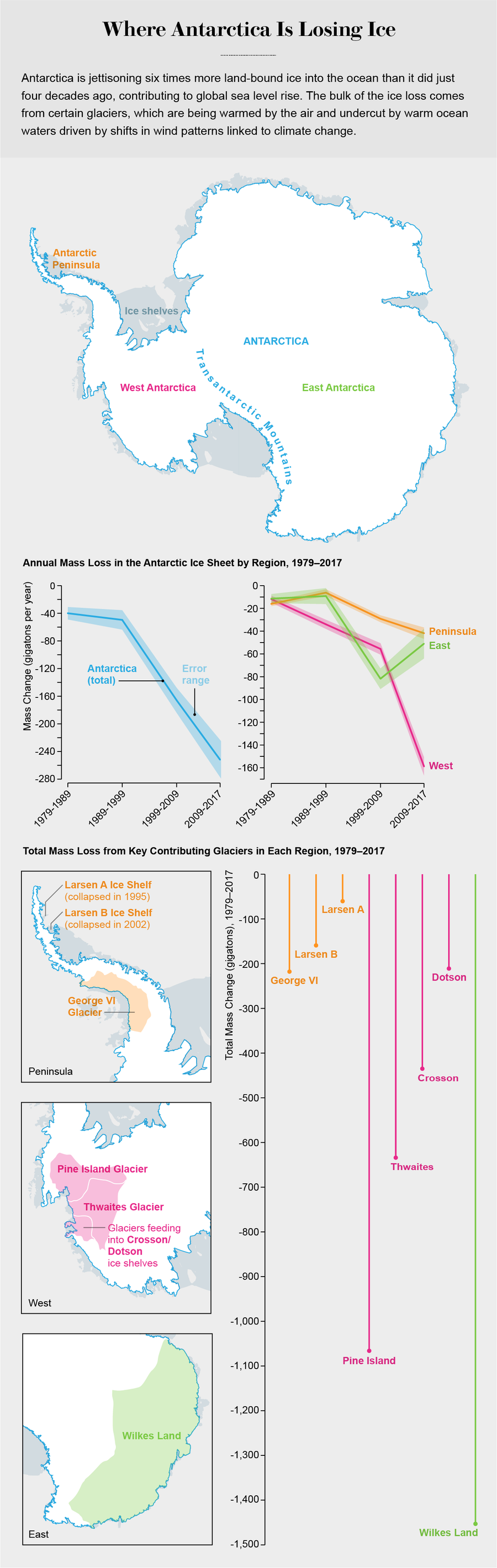

The amount of ice being sloughed off the massive land-bound ice sheets that blanket Antarctica has ratcheted up significantly in the last four decades; the continent is now losing six times more ice than it was in the 1980s. With climate change likely to continue accelerating this melt, the implications for global sea level rise are considerable.

These conclusions come from a new study that marshals improved data sets and was published this month in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. It found Antarctica as a whole went from losing about 40 gigatons of ice per year in the 1980s to 252 gigatons per year over the last decade. (One gigaton is a billion tons.) All that ice dumped into the ocean has raised global sea levels by 14 millimeters since 1979, according to the study. West Antarctica, home to some of the fastest-flowing and fastest-melting glaciers, accounts for the bulk of the loss calculated in the new work. But the research shows melt in East Antarctica—long thought to be the more stable region—has been underestimated.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: “Four Decades of Antarctic Ice Sheet Mass Balance from 1979–2017,” by Eric Rignot et al., in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol. 116, No. 4; January 22, 2019

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

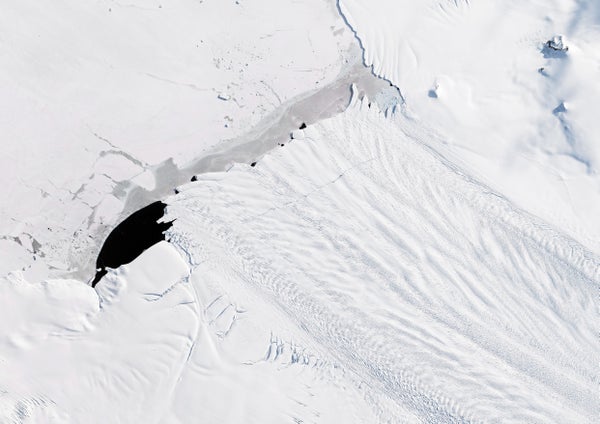

Within each main region of Antarctica (East, West and the Antarctic Peninsula), ice loss has been concentrated in certain sectors over the last 40 years, the new study finds. The common thread among them is the infiltration of relatively warm ocean water below the ice, thinning it and causing the glaciers to flow out to sea faster. Researchers think the warmer water intrusion is driven by changing wind patterns linked to global climate change.

The graphic below shows how ice loss has sped up across Antarctica as a whole—by each region and by several of the most rapidly changing glaciers. Recent findings suggest some of those glaciers, such as Pine Island and Thwaites in West Antarctica, may have reached a point of no return at which their loss cannot be reversed. Thwaites is of particular concern because it is a linchpin holding back a significant portion of the larger West Antarctic Ice Sheet, and could unleash considerable sea level rise were it to disintegrate. A major scientific mission is currently investigating the glacier to better understand how it is changing and to better predict how much sea level rise is in store for the world.