MONROVIA, Calif .— NASA’s next major interplanetary mission is the Mars 2020 rover. The robot explorer is expected to touch down on the Red Planet in February 2021, but there is one key detail that remains to be decided: Where exactly it will land.

Wherever the rover finds itself in 2021 will likely shape the future of Mars exploration for decades to come. Besides poking around its landing site for signs of past habitability and Martian life, the rover will also select and cache samples for an eventual return to Earth at some yet-to-be-determined date. Once gathered, the precious samples will unquestionably beckon us back to Mars, even if no one yet knows what secrets they shall hold or whether humans or robots will retrieve them.

Twice before, mission planners have gathered to winnow their overlong list of candidate landing sites, each time emerging with a smaller number of high-priority places to go. From February 8 to 10 some 250 planetary scientists and spacecraft engineers gathered here for their third confab—the penultimate meeting before Mars 2020’s final landing site is chosen. A fourth workshop to ruminate further about the remaining candidate sites is slated for early to mid-2018, after which NASA’s leadership will pick the rover’s final destination.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The Mars 2020 rover puts on the brakes, utilizing its sky crane coupled with onboard navigation software to autonomously steer clear of surface hazards and land safely.

Credit: NASA/JPL–-CALTECH

Experts watched the proceedings from around the world, anticipating the fateful decision that is the closest thing in planetary science to the puff of white smoke that emanates from the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel chimney announcing the election of a new pope. After days of deliberation, debate, polling and backroom banter among a select group of Mars officialdom, their announcement of the top landing sites at last arrived, whittling the previous set of eight candidates down to just three areas.

Candidate Sites

The top three sites still in the running for Mars 2020 are Northeast Syrtis Major, Jezero Crater and Columbia Hills/Gusev Crater—the latter a place already surveyed by NASA’s Spirit rover from 2004 to 2010. All three lie near Martian equator, a region more accessible to surface missions than other parts of the planet. “NE Syrtis and Jezero were the highest-rated sites,” says Ken Farley, Mars 2020’s project scientist and professor of geochemistry at Caltech.

Jezero Crater hosts an ancient dried-up lake that could possibly be a repository of past microbial life. Northeast Syrtis Major is a huge shield volcano abutting an immense impact crater, in a region thought to have once been warm and wet.

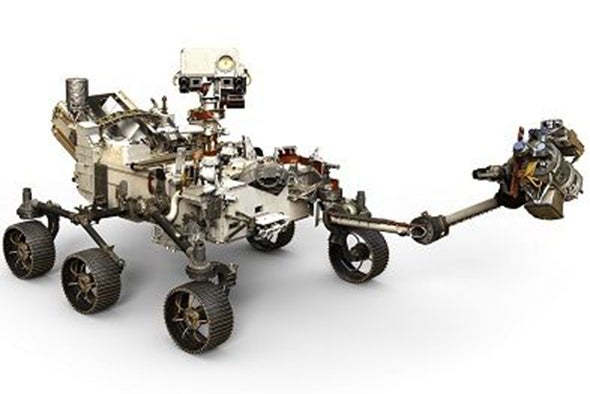

Computer artwork of Mars 2020 rover with outstretched robotic arm.

Credit: NASA/JPL-–CALTECH

Of the trio of sites, the thought of spurning virgin territory for a robotic return to the Columbia Hills spurred heated chatter. Advocates of that place explained that prior to Spirit becoming bogged down in sand and eventually expiring there, the robot found an old, eroded volcanic ash deposit. Paired with other observations, that sign of volcanism suggests a hot spring was active in the area long ago, boosting the site’s potential for harboring signatures of past Martian life.

The debate over Columbia Hills reached a crescendo just prior to the workshop’s close, when a landing site steering group vetoed the locale—a decision that was subsequently overturned. “In considering Columbia Hills, the selection committee recognized the potential strength of the site as well as a variety of uncertainties,” Farley says. “The group decided that further study of the Columbia Hills site was warranted to establish a better picture of the site’s geology and what the mission could accomplish there.”

A Smarter “Seven Minutes of Terror”

From an engineering perspective, the Mars 2020 mission is very much a mirror image of the Curiosity robot that has been busily working on the planet since August 2012. Getting this next rover down and dirty on Mars utilizes the same entry, descent and landing approach—a nail-biting plunge through the atmosphere cheerily known as “seven minutes of terror” that culminates with a “sky crane” firing retro-rockets and hovering over the surface as it carefully lowers the rover onto Mars. This time, however, the Mars 2020 hardware will possess new systems to attain a more precise landing spot and to make last-minute maneuvers to avoid hazardous boulders, slopes and sand traps.

Michael Meyer, lead scientist for NASA’s Mars Exploration Program, details the Mars 2020 rover mission during the landing site workshop.

Credit: Barbara David

Moreover, once grounded the rover will operate with more autonomy compared with Curiosity, thanks to a batch of software upgrades. Jennifer Trosper, system engineering lead for the rover at Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), says those improvements can assure no dillydallying on Mars.

Enhanced navigation across all kinds of complex terrain means Mars 2020 can get its primary scientific chores done far more efficiently and quickly than Curiosity ever could, Trosper says. Indeed, the rover must perform its tasks significantly better relative to Curiosity to achieve its mission objectives, she says.

Stash a Cache of Mars

A keystone goal for the nuclear-powered Mars 2020 rover will be to rigorously document, then gather and stash an “astrobiologically relevant” cache of Martian samples for future transport back to Earth. “Mars 2020 is not a life- detection mission, but I think targeted to the right place we can make great strides toward finally answering the question about life on Mars. It gets us down the road” to find out, says John Grant, a geologist at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum’s who co-chairs of the Mars 2020 Landing Site Steering Committee.

“On the science side, it’s all building towards Mars sample return,” says David Beaty, chief scientist for the Mars Exploration Directorate at JPL, who is also co-leader of the Returned Sample Science Board set up by NASA as an independent diverse group of scientists. He views the Mars 2020 rover as a “huge step forward” in flinging to Earth bits and pieces of Martian manna. All in all, the robot is to stuff into sample-collection tubes on the order of one half kilogram of Mars. Once those Mars-loaded tubes are back here on terra firma, the specimens would undergo analysis through the miracle of modern instrumentation. “We can basically throw the book at the samples,” Beaty says. “I see Mars samples as a major divergence in our planning for the future. Either the samples have life in them or they don’t. If they have life in them, then the Mars program takes off in a totally different direction.”

Ray Arvidson of Washington University in Saint Louis, Missouri sees Martian samples returned to Earth as a logical progression of decades of research on the Red Planet.

Credit: Barbara David

Scientists worldwide are already planning for their own laboratory close encounters with any fresh delivery of Martian flotsam. “We have been trying to get return samples for decades,” says Ray Arvidson who directs the Earth and Planetary Remote Sensing Laboratory at Washington University in Saint Louis. “Sample return is so expensive, so complicated,” he says, but is a logical progression of Mars orbiting missions, geologic explorers and Curiosity’s habitability findings. “The next step is selecting the right place, do some in situ measurements and then get the samples back sometime in the next decade,” Arvidson adds. He favors robots over humans hauling back the goods because automatons are cheaper and faster.

Plans and Hopes

There is a problem, however. Missing in action is a firm NASA plan for what comes after Mars 2020. In fact, the rover is currently NASA’s last funded mission to the Red Planet. Arvidson and many other Mars scientists are optimistic that bots will bring home the astrobiological bacon as soon as the 2030s—but how, when and at what cost those specimens will actually return to Earth remains anybody’s guess. “It’s a money question, not a science question,” Beaty says. “And the money comes from Congress and the Office of Management and Budget, with priorities set by the White House.”

Michael Meyer, lead scientist for NASA’s Mars Exploration Program, puts it more bluntly: “We don’t know…. We don’t have in the budget what we’re going to do after 2020. Certainly we have plans and hopes.” He sees Mars 2020’s sample cache as a culmination of more than a half century of exploration that began with the first Mars flybys of the 1960s, all bent on learning whether or not that faraway world was an extraterrestrial address for life— in the past or right now. Thanks to Curiosity, yes, we now know with certainty Mars possessed all the right ingredients for life early on, he adds. “Is it possible Mars could have supported microbial life? This Mars 2020 mission is going to address that question…and it looks like we’re on the right track,” he says.

Some 250 scientists and engineers from around the world attended the third workshop that seeks to determine the best landing site for the Mars 2020 rover.

Credit: Barbara David

On the other hand, even the best-laid plans can go off the rails, particularly if the “ground truth” at Mars 2020’s final landing site is less alluring than experts had hoped. There is no guarantee for a second chance at sample collection, no promise of another mission to another locale if Mars 2020’s is found to be lackluster. As the pressure builds to make the right call, it is also deepening rifts between competing campsof thought about the best possible place for the rover to go. “The more information you get about a place like Mars…the tougher it is to address these questions in a black-and-white manner,” explains David Des Marais, a senior astrobiologist at NASA Ames Research Center .

“Now you’re seeing a split in the astrobiology community between different [Mars] environments. It’s sort of a feudalistic landscape…and feudalism even amongst the astrobiologists,” Des Marais says, in which the success or failure of researchers’ careers may intimately depend on which landing site they throw their weight behind. He points out NASA’s mantra for seeking life on Mars used to be “follow the water.” But “that’s not adequate anymore,” he says, because water on Mars has proved to be quite widespread. “Now we need to discriminate between places that have water—which are better, which are less so? And that’s where habitability comes in. So let’s raise the bar here.”

As for the possibility a lack of funding could end NASA’s enduring love affair with Mars, Des Marais is sanguine, just like most of his peers: “That’s always the case. The end of the road is a good thing…because you can keep building the road.”