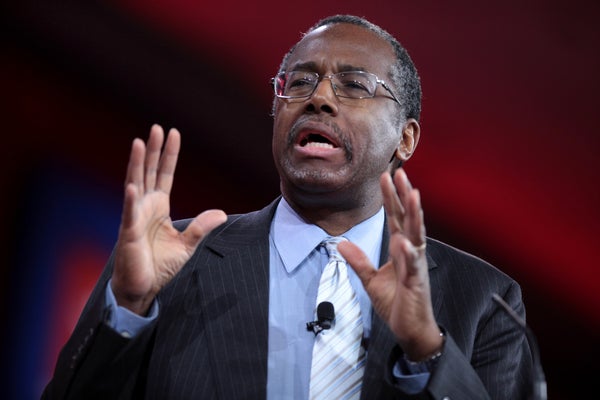

Although many in the housing rights field were initially dismayed at the prospect of neurosurgeon Ben Carson becoming Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, the leaders of some advocacy groups now hope he can make a positive difference—if he applies his medical background to attack some of the dangers that have long lurked in low-income housing.

President-elect Donald Trump last week announced he would nominate Carson to lead HUD. The nominee grew up in subsidized housing but lacks any government experience—a fact that has drawn scathing criticism from Democrats—and a spokesman for the onetime GOP presidential candidate indicated before his nomination was announced that Carson believed he would be better placed to serve as a Trump adviser.

Carson has not publicly discussed what his plans would be if the Senate confirms his appointment. But his nomination comes as groups that deal with HUD say it must do more to address the health of those living in federally subsidized apartments and other types of homes. Studies have shown that housing—or the lack of it—has significant effects on both mental and physical health. A report this month saying Americans’ life expectancy has dropped for the first time since 1993 is fueling advocates’ concerns. “Poverty and unstable or unhealthy housing is the most under-recognized public health crisis of the 21st century,” says Emily Benfer, a law professor and director of the Health Justice Project at Loyola University Chicago. “As secretary of HUD, Dr. Carson has an unparalleled opportunity to make a profound impact on and create positive health outcomes for millions upon millions of individuals. That’s more patients than any one physician could ever treat.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

A main priority for Benfer and others is how HUD maintains its statutory commitment to cleaning up lead paint in public housing. The agency’s Office of Lead Hazard Control and Healthy Homes funds state and local cleanup efforts, enforces lead-based paint regulations and provides public outreach. High blood-lead levels are linked to learning disabilities and other problems among children. Elevated levels are more prevalent among those who come from lower-income families, and inadequate nutrition can increase the body’s lead absorption. A presidential task force 16 years ago called for an end to childhood lead poisoning by 2000 but the problem persists in many cities, as flat funding has greatly slowed efforts.

Experts say HUD’s standards for reducing lead paint risks need revising. The current standards “require a child become lead poisoned before initiating robust lead hazard inspections, and multiple public housing complexes are located on or near former industrial sites with high levels of neurotoxins and carcinogens in the environment,” Benfer says.

Charlotte Brody, director of Healthy Babies Bright Futures—a project seeking to reduce health risks to infants—says Carson and others in the Trump administration should include lead removal from homes and other spots in the president-elect’s proposed infrastructure plan, which has an estimated price tag of as much as $1 trillion. “Trump’s commitment to rebuilding infrastructure, and rebuilding inner cities, could be two very important opportunities to eliminate lead poisoning,” Brody says. “Infrastructure isn’t just bridges and highways.”

Other health-related issues that Carson could focus on, advocates say, include maintaining a new ban on smoking in public housing as of fall 2018 to reduce the risk of exposure to secondhand smoke. That rule—which has drawn withering criticism from smokers who say HUD is infringing on their personal rights—could be overturned in a Trump administration. But outgoing HUD Secretary Julián Castro said he is optimistic the rule will survive because the health benefits are so significant. HUD has worked with other agencies in recent years to improve education and start pilot programs to address asthma, a particular problem for people in public housing.

About one fifth of the nation’s public housing agencies already have some form of smoking limitation in place, and many low-income housing developers “have already been there, done that” on the issue, says Gina Ciganik, CEO of the Healthy Building Network. The nonprofit seeks to reduce the use of potentially hazardous chemicals—such as lead, cadmium and phthalates—in flooring and other components involved in building projects. “HUD is probably a little bit behind,” says Ciganik, who worked as an affordable-housing developer in Minneapolis until last year. “We have found that as long as you created a safe outside separate area and offered incentives to get people to quit…, most people appreciated it and were fine with going outside” to light up.

If confirmed, Carson could also press HUD’s Real Estate Assessment Center (REAC) offices to check public housing areas more thoroughly for hidden health hazards, says Kate Walz, director of Housing Justice at the Sargent Shriver National Center on Poverty Law. “The primary focus [of the inspections] is on common areas and the external features [of buildings], and not on the interior of the units, which is the biggest health contributor,” Walz says.

Ruth Ann Norton, president and CEO of the Green and Healthy Homes Initiative, says Carson should seek to have the agency look “holistically” at how flaws in low-income housing contribute to health declines, rather than just concentrating on a single problem at a time. She says her nonprofit, which researches ways to make homes less illness-prone and more environmentally beneficial—has called for comprehensive efforts with multiple and integrated components: They combine reducing lead hazards with weatherization to protect homes from storms and other hazards, as well as installing energy-efficient devices and educating residents about health and environment risks. “It’s much like a doctor—they don’t just look at a shoulder when they see you, they look at your whole body,” Norton says. “Just the same way, we should look at a house and see what is causing the undermining health effects.” Her group conducted a 2014 study that found such an approach reduced hospitalizations 65 percent and emergency room visits 27 percent. If HUD adopted the approach on a widespread basis, “you’re looking at a significant savings in Medicare and Medicaid dollars—that’s something that’s an immediate return,” she notes.

Ciganik says her group’s work to encourage developers to use less-toxic building materials in tile, drywall and other areas also could be a focus for HUD. This year the group started an initiative in six communities to incorporate safer materials in developments, which it says can reduce the amount of hazardous chemicals in a single 90-unit apartment building by more than 15 tons.

Despite Carson’s lack of government experience, Ciganik calls his medical background “an interesting attribute,” especially in communicating to the public the health-related aspects of the job if he is confirmed. But, she adds, “I also know that—after spending 20 years in the affordable housing world—it’s really complex. I hope he’s open to understanding the nuances and broader implications” of the agency’s work.