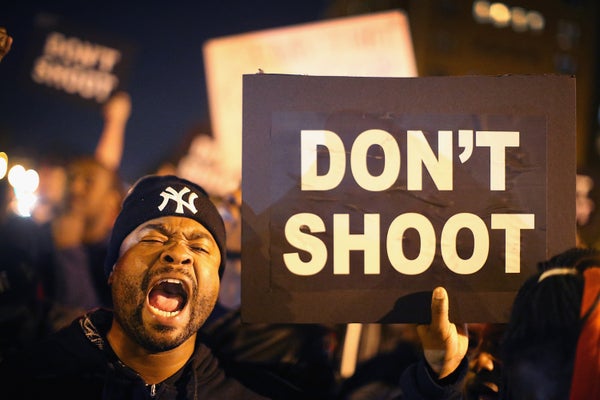

In the latest police shooting of an unarmed black man, an officer in North Miami this week shot Charles Kinsey—a therapist who was lying on the ground with his arms in the air. He had apparently been trying to help a patient with autism who was sitting in the street. Kinsey survived, but the incident follows lethal ones in Minnesota and Louisiana and the murders of eight officers in two states.

Police, policy makers and scientists are scrambling for answers about how to combat excessive—and often deadly—force against African-Americans. Many researchers say a first step might be to obtain better data on how often police departments use physical force against people, and under what circumstances. A think tank called the Center for Policing Equity this month published the strongest data yet on how often officers use force on the job and how those actions differ according to the race of the people involved. The data echo what is playing out in near-daily headlines: Across geographically and demographically diverse swaths of the country, physical force —via restraint, punches, tasers and guns —is disproportionately exerted against black people, even after taking into account differences for violent crime arrest rates and other factors.

That conclusion comes from data spanning the years 2010 to 2015, voluntarily provided by 12 police departments across the country. The identities of departments were kept anonymous in the report.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

University of California, Berkeley’s Jack Glaser, an expert on implicit racial bias among police and co-author of the new report, spoke with Scientific American about the Center’s work, ways to confront bias, and the many questions that seem impossible to answer in a country stunned by the escalating violence.

[An edited transcript of the interview follows.]

We know that police officers, like the rest of us, can be subject to implicit bias. Can you briefly describe what that is?

Implicit biases reflect positive or negative mental associations that people have between groups, like racial or ethnic groups, and specific traits like criminality or danger. They are implicit in the sense that they reside in the part of our memory that is not accessible to conscious introspection. They get activated in our memories when we encounter somebody from one of those groups or when we think about those groups. It’s maladaptive when it causes us to make biased judgments about individuals based on prior conceptions about the groups they belong to.

Groups including your think tank, the Center for Policing Equity, have worked to design programs for police officers that aim to help combat implicit bias on the job. What does this training look like?

A lot of people are calling for implicit bias training, including Hillary Clinton. They typically look like lecture-based and discussion-based conversations about what implicit bias is, and how it influences your judgments and causes you to make discriminatory judgments.

Do we have actual data showing that this training changes officers’ actions in the field?

Unfortunately none of them have been shown to have any actual impact on performance. You can raise people’s awareness about the possibility that implicit bias exists and affects them, but that’s not the same thing as stopping it from influencing their judgments. The nature of implicit bias is that you can’t feel it operating. There are internal reports evaluating these programs, but they haven’t been published in the peer-reviewed research. Generally, we are still working with very little information.

What the scientists will tell you is that you shouldn’t be calling this ‘training’ because you don’t want to give people the impression that their behavior is being changed. It’s raising awareness. It is possible that the process of talking about biases, if not done correctly, can reinforce them—or that when people believe they’ve been de-biased or trained they feel credentialed to go about their business without worrying about bias as much, which could actually increase bias.

So how do we get good data?

We are building this national justice database at CPE and are hoping to be able to look at the effects of these [implicit bias] trainings on actual performance outcomes. We don’t have any existing comparable data across police departments. If you were going to test this within a department you would randomly assign some units to do it and compare their actions, but that hasn’t been done. At best you get some explicit attitude change, but no implicit attitude change and no improvement in performance.

If implicit bias workshops may not be the answer, what can police departments do?

We don’t know how to de-bias people because the culture is so saturated with those stereotypes. My general recommendation is—and I think it’s consistent with what the Center for Policing Equity is generally proposing—that departments find ways to reduce the rates at which these interactions are occurring.

Meaning what?

Police have a lot of discretion on who they can engage with and who they detain, and that can result in wild variation in discretionary stops. You can reduce the amount of contacts without compromising public safety and then the chance for biased outcomes gets reduced dramatically. We have seen that in NYC: The number of stops are way down and the racial disparities are mathematically necessarily reduced because there is less room for disparity.

The 12 departments that gave you their data voluntarily were told that they would be kept anonymous. How do you know the data are accurate?

We are always concerned about the accuracy of self-reported data. Our hope is by keeping this anonymous we will hedge against that.

As the database gets bigger— we have many more lined up to join beyond these 12—we will see a large proportion of the U.S. population represented. My expectation is within a year or two we will, conservatively, have police departments covering half the U.S. population represented. We are targeting large departments. The concerns are still there about the accuracy of the data that is being reported. Some of them just send PDF files with summary statistics. We are working with all of these departments to collect raw data to be sent to us at the incident level but there is a lot of variation there.

This is the first public data on this issue. How did you make it happen?

CPE has been working for years now to build relationships with police departments, that’s a big part of it. There is this existing relationship between CPE and some big city chiefs and some smaller towns too. We got a grant from the National Science Foundation and some additional funding from some private funders so we could pull together a team of researchers and staffers to make this happen. We have some retired police on staff who are doing this outreach. That’s very helpful.

Any other good data-driven areas you are hopeful about to combat unnecessary use of force?

Community policing is an ill-defined concept and every police department will say they are doing it. To have good data on that you would need it to be comparable in areas where there is variation in style of policing, or areas where they are doing it versus not doing it. The national justice database is trying to get at part of that. It’s hard to say what specifically works until we know who is doing what.

One thing I am enthusiastic about is the psychology of intergroup contact in policing. Mere contact with members of different groups— racial, ethnic, sexual orientation, ideological, national— as long as it’s not negative, competitive contact, reduces bias toward other groups. There’s been some great work on this that I hope we can inject into community-oriented policing.