A Latina essential worker who lives in Montgomery County, Maryland, drove an hour and a half south to the nearest pharmacy where she could get her COVID vaccination. When she arrived, staff asked for identification, and she showed them her El Salvador passport. They then asked for a U.S. ID and social security number. She did not have either of them because she is undocumented, and she panicked (even though proof of legal residency was not required for getting a vaccine).The woman sought help from a local volunteer group called the Vaccine Hunters, or las Caza Vacunas, which contacted a Maryland state delegate. That delegate called the pharmacy, which initially hung up on them. But the Vaccine Hunters ultimately persuaded the facility to administer the woman’s shot.

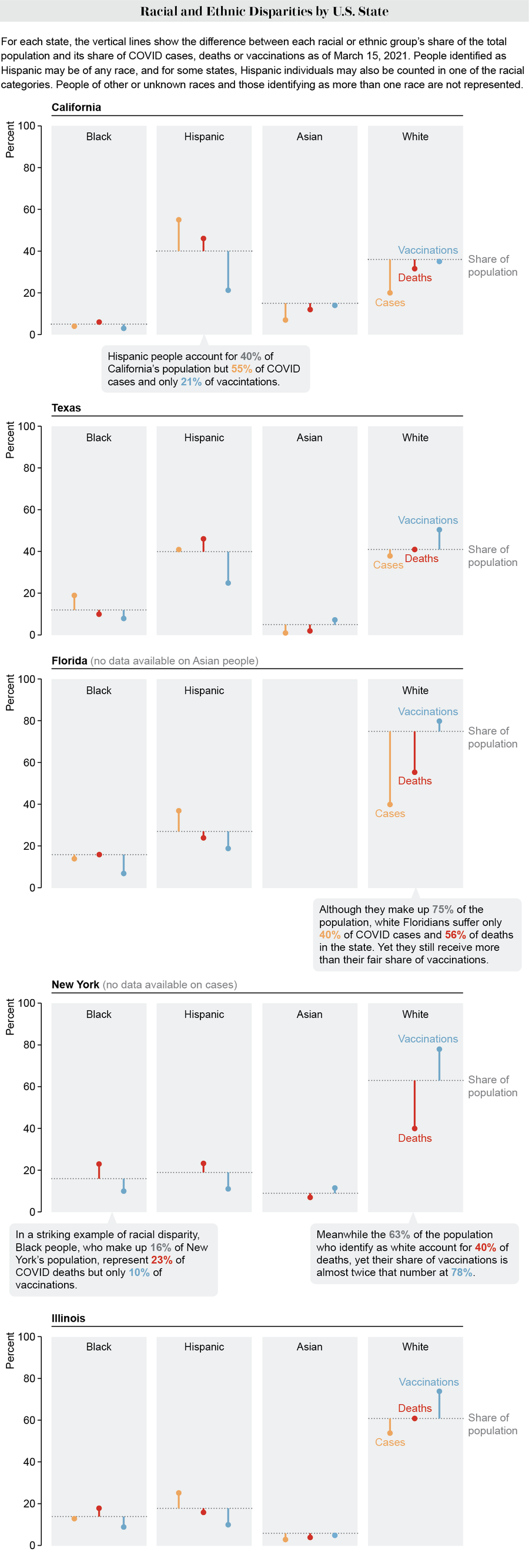

Stories of such inordinate hurdles are fairly common and may help explain why Hispanic and Black people in many states are getting vaccinated at disproportionately lower rates than white or Asian people—despite having a higher burden of COVID-related death and disease.* The Kaiser Family Foundation collects data on COVID cases, deaths and vaccination rates among people who identify as Black, white, Asian or Hispanic. Scientific American visualized these data for five populous states with some of the worst COVID outbreaks: California, Texas, Florida, New York and Illinois. The graphic below shows that Hispanic people had some of the lowest vaccination rates proportional to their share of the population, especially in California and Texas. Black people in New York, Illinois and Florida are getting vaccinated at notably lower levels as well.

Many factors may be behind these discrepancies [see additional graphics]: Age minimums for COVID vaccination could favor white Americans, who have a longer life expectancy than Black Americans. Poor Internet access may make securing vaccine appointments a challenge. And not owning a vehicle or living near public transit makes it harder to get to vaccination sites. For some immigrants, language barriers and onerous proof-of-eligibility requirements add more difficulties.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: Kaiser Family Foundation

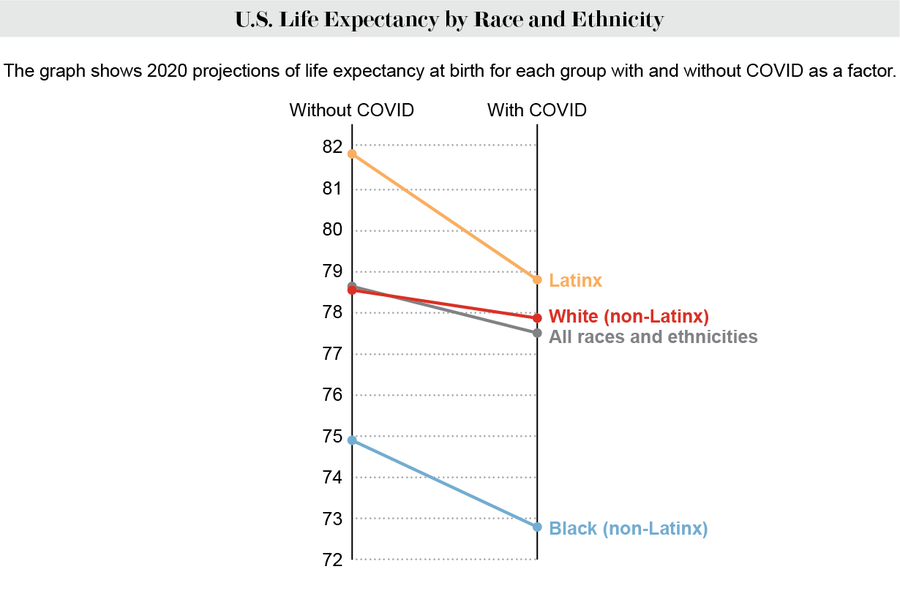

One of the primary qualifications for a COVID vaccine in many states is being older (typically age 60 or above), which is known to be among the biggest risk factors for severe disease and death from the novel coronavirus. But because of Black Americans’ shorter life expectancy, fewer of them may be eligible for a vaccine—despite being at a higher risk of death than similar-aged or older white people.

Twin physicians Oni and Uché Blackstock wrote about this disparity in a recent Washington Post op-ed calling for lower age limits for Black people to get vaccinated. “These age cutoffs ignore the impact of systemic racism on shortening Black Americans’ lives,” Uché Blackstock, founder and CEOof the organization Advancing Health Equity, told Scientific American. “Ignoring the fact that we’ve had Black Americans of younger ages die at higher rates than white Americans—even 10 years older than them—I think reinforces these inequities.”

Interestingly, Hispanic people in the U.S. have a higher overall life expectancy than non-Hispanic white people, despite generally having a lower socioeconomic status. This has been called the “Hispanic paradox,” or “Latino paradox.” Possible explanations include the “healthy immigrant effect”—the fact that recent immigrants tend to be healthier than the locally born population—as well as behavioral factors such as diet and lifestyle. But Latinx people have also had the greatest drop in life expectancy because of COVID, so it does not make sense to raise the age cutoff for vaccination in that group.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: “Reductions in 2020 US Life Expectancy due to COVID-19 and the Disproportionate Impact on the Black and Latino Populations,” by Theresa Andrasfay and Noreen Goldman, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, Vol. 118, No. 5; February 2, 2021

“Right now the most pressing barrier is truly the restriction around age only and not allowing for race to be carved out as its own category,” says Nneka Sederstrom, chief health equity officer at Hennepin Healthcare in Minnesota. “What we’re finding is: When you look at life expectancy—especially in places like Minnesota that have a huge elderly population—yes, the elderly groups are dying. But when you adjust [the data] per population, then you see that the populations that are dying the fastest and the most are populations of color. And they’re dying way before they hit the age range that white people are dying at.”

The problem stems from “a deep-rooted inability to name race as its own factor” in disease risk, Sederstrom says. She adds that every lawyer she has consulted contends that singling out race as a criterion for eligibility violates the 14th Amendment, which extended citizenship and equal rights to Black Americans and anyone born or naturalized in the U.S. “If you're saying that the amendment that gives us the opportunity to supposedly address equity and equality is the thing that’s in the way of actually addressing equity and equality,” Sederstrom says, “then we need to change that.”

Some regions have already been able to use lower age cutoffs for vaccinating Native Americans, who have also become sickened and died at higher rates during the pandemic.

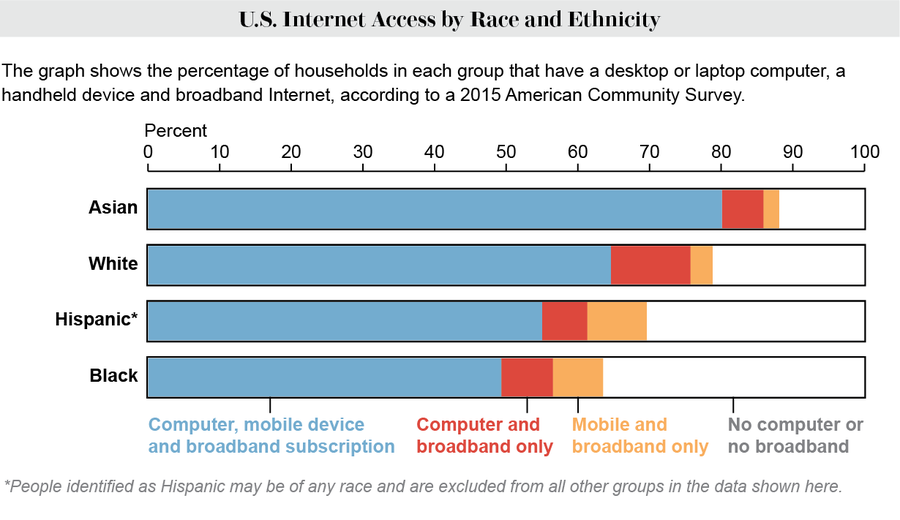

Another barrier to getting vaccinated is difficulty in registering for appointments online. Applicants often have to navigate labyrinthine portal systems and fill out multiple pages of documentation before appointments fill up, so it becomes a race for who can load and complete the forms the fastest. A 2015 survey found that a smaller percentage of Black and Latinx households have computer and broadband access than white and Asian households. And many people of color work in hourly jobs that do not give them time off to spend long stretches of time looking for vaccine appointments.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: U.S. Census Bureau

In Maryland, the Vaccine Hunters have been helping seniors and people of color register for appointments. “It became a game of ‘How quick can you type?’” says Maria Peterson, a member of the group. “It’s like The Hunger Games.”

One problem for Hispanic people has been Web sites with poor Spanish translations—often resulting from a typical automated tool. “The grammatical errors we found would have made it impossible for a Spanish speaker to figure out what was being asked,” says Peterson, a native Spanish speaker who teaches the language at the high school level. That confusion could waste valuable time as appointments fill up. Her team members reported one registration system’s poor translation to the local government, and within days they were meeting with county officials to improve it. “If it’s an official document, and it’s not written properly, it loses credibility,” Peterson says.

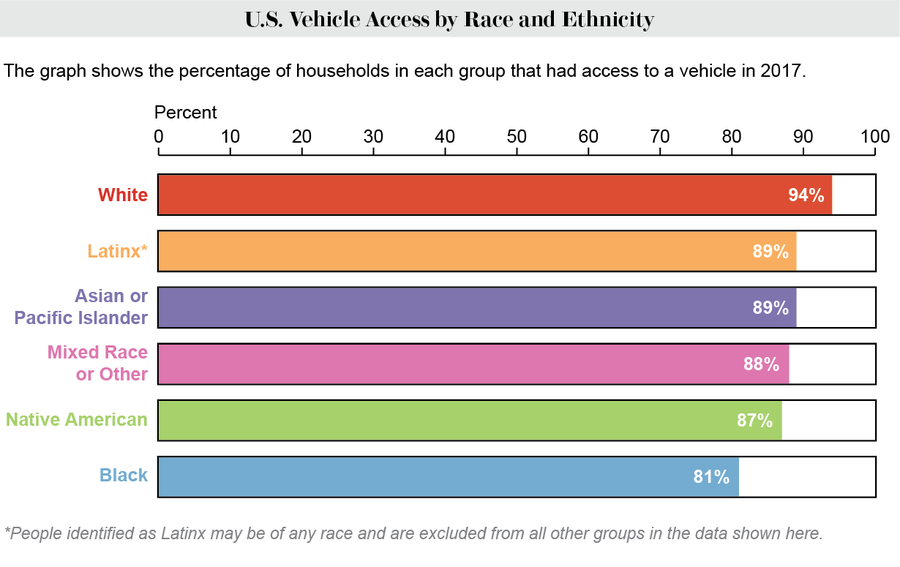

Getting to vaccination sites can also be a challenge. They are not always near public transit, and not everyone has access to a car. An analysis of survey data found that in 2017 Black households were the least likely of any racial or ethnic group in the U.S. to own a vehicle, followed by Native American households. Montgomery is Maryland’s most densely populated county, with a good metro system and buses. But its closest mass vaccination site is at a Six Flags America theme park, which is a several-hour bus ride from most parts of the county.

In Chicago’s South Side, which is predominantly Black, one must make a 30-minute drive or take a roughly hour-long bus ride to get to the mass vaccination site at the United Center in the city’s downtown area, says Armani Nightengale, a contact tracer at the Calumet Area Industrial Commission who is also helping people make vaccination appointments. “We had an instance of appointments opening up the day of, and we asked people if they wanted to come in today,” Nightengale says. “One lady was like, ‘Are you kidding me? How am I going to get there?’” Many people have work or are taking care of children and cannot just drop everything to get vaccinated. Taking public transit poses a potential COVID exposure risk, and ride-sharing is expensive, she adds.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: National Equity Atlas

In addition to these barriers, there is the issue of vaccine hesitancy. Black Americans are still more likely than white Americans to resist getting a vaccine, although this gap has decreased over time.

Uché Blackstock believes many of the concerns people have about vaccination are addressable. “A lot of people of color who have concerns about the vaccine are not an adamant ‘no,’” she says. “A significant proportion are ‘wait and see.’”

“Hesitancy doesn’t mean refusal,” Sederstrom notes. There is an attitude that “we don’t actually have to do this extra work that we need to do to go to this community, because they’re hesitant,” she says. “Let’s take a step back and figure out why is there distrust and address that. But hesitancy is not an act of refusal.”

*Editor’s Note: The term Hispanic refers to people of any race whose heritage is in Spanish-speaking countries. Latinx is a gender-neutral alternative to Latino and Latina that refers to those of any race whose heritage is in Latin America. For the purposes of this article, these terms are used somewhat interchangeably, although most of the demographic data employ Hispanic.