This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

The 2019 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was just announced, and the winners, as usual, are people of incredible accomplishment. But each year, before the new laureates are presented to the world, I think of one who is perhaps the ideal role model for what a Nobel Prize winner should be. I am not deeply familiar with all 219 laureates in the category of medicine since 1901, but I would dare to single him out—both for what he did and how he did it.

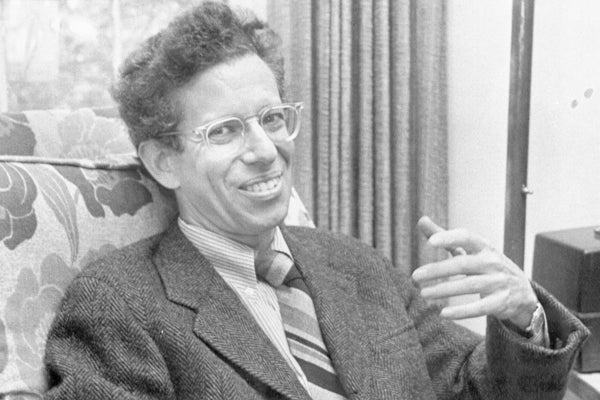

A professor here at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, Howard Temin represented what society expects from us and had the characteristics that make society willing to fund our work. People want scientists who get up every morning committed to finding the truth.

Living up to those expectations is more important now than ever. At a time when science and facts are under fire, we face a more skeptical public. And the whole scientific enterprise is so wrapped up in competition for rankings and grant dollars that our priorities are becoming skewed.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Temin shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1975 for “discoveries concerning the interaction between tumour viruses and the genetic material of the cell.” His decades of work on an obscure tumor-causing virus in chickens resulted in the discovery of an enzyme that changed our understanding of the most fundamental aspects of biology and launched the recombinant DNA revolution.

The scientific establishment originally thought he was wrong, and he was ridiculed and ostracized for years. Yet he kept at it, and even after his careful work and scrupulous application of the scientific method resulted in a revolutionary breakthrough, he didn’t seem resentful of the way he had been treated. His moral compass was so powerful, he didn’t hesitate to chastise European royalty for smoking during the ceremony in Stockholm when he accepted his Nobel Prize for work on cancer.

Temin’s discoveries led to all kinds of breakthroughs, including our ability to understand and battle HIV,the introduction of recombinant DNA technology and the emergence of the genetic editing of today. Recently a Lasker Award was given for the development of a drug directed against a protein on the surface of breast cancer cells called HER2. This work would not have been possible without Temin’s discovery. Now people with HER2 are among the most treatable. It’s amazing where curiosity about a chicken virus can lead.

I first encountered Temin when I was a young assistant professor in the School of Medicine at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, years after he had won his Nobel. We didn’t yet appreciate how much he had changed the world, but we admired him just as much for the kind of person he was. In contrast, there are some famous scientists who, as human beings, resemble the south end of a northbound horse.

We can all learn from the way Temin relentlessly pursued his North Star. First, he impeccably followed the highest standards of research and would chide others if they didn’t adhere to the fundamentals. He maintained a high bar for healthy skepticism and objective evidence, and he didn’t assume he was infallible.

Second, he was not in it for personal fame. Society is fine with somebody achieving renown for doing really good science but will be unhappy about committing resources to scientists whose prime interest is in their social media profile. And third, he lived and shared the joy of science, continuing to personally teach and mentor his students when many famous researchers become distant and impersonal.

So how do we ensure there are more scientists like Temin? The leaders of our research institutions should not be slaves to metrics. The best institutions are willing to pick the right people and then give them space to pursue their obsession in a novel way. They recognize that research is the act of exploring blind alleys on the way to an important discovery.

Outstanding leaders are willing to take risks themselves. What many people mistake for leadership is simply managing the metrics. If the mission of an organization is only to reach a set number of papers or grants in a five-year period, such quantitative guidelines are safe for a leader, but a potential Temin is doomed.

At the Morgridge Institute for Research, for example, our goal is to be the kind of place where the Howard Temins of the world want to be. We think it is better for science not to measure performance by grant dollars—but rather to take the time and put in the effort to make judgment calls based on the quality and trajectory of the work.

Young scientists have a role to play as well: Demand change. If you think your leaders are leaning too heavily on metrics and avoiding the personal responsibility of making judgment calls, you ought to tell them that. Remember, good leaders only lead by the permission of the people they serve.

Temin was the scientist our society would like us all to be. Let’s hope this year’s Nobel Committee helps to light the way for others, too.