Christopher Intagliata: Nearly 350 years ago, the Dutch scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek scraped some white stuff off his teeth—“as thick as if ’twere batter,” he wrote—and peered at it under one of his handmade microscopes. What he saw was alive—he described it as “many very little living animalcules, very prettily a-moving.” The biggest of which “shot through the water (or spittle) like a pike does through the water.”

What he had discovered in the plaque from his teeth—the “animalcules”—were bacteria. Before van Leeuwenhoek’s observations of bacteria ...

Lambert van Eijck: Nobody could have discovered bacteria because they didn’t have the resolution.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Intagliata: Lambert van Eijck is a materials scientist at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. He says some of van Leeuwenhoek’s microscopes could magnify things more than 200 times. And contemporaries, like Robert Hooke in England, who’d written a book full of microscopic observations—were stunned by his findings.

Van Eijck: The interesting thing is Robert Hooke spent quite some effort trying to discover why was Antoni van Leeuwenhoek so skilled and what kind of mysterious ways of producing lenses made him able to see, for the first time, bacteria.

Intagliata: But Van Leeuwenhoek wasn’t eager to reveal the secrets behind the hundreds of microscopes he built.

Van Eijck: Some people had explicitly asked him about the lenses, and he never said anything about it. It’s still a big mystery how these lenses were made after 350 years. The only way they could discover is to break one open. And then you would obviously see what the lens would be like. But they are too precious.

Intagliata: That’s where Lambert van Eijck comes in. He and his colleagues were able to peer inside several of van Leeuwenhoek’s microscopes with a nondestructive technique called neutron tomography. It’s the same idea as a CT scan but uses neutrons instead of x-rays.

And what they found surprised them. Instead of using lens types unknown to other scientists of his day, van Leeuwenhoek had installed a common type of ground-and-polished lens in one of the microscopes they examined. And in the other, one of his most powerful scopes, he had used a globe-shaped lens produced by flame working—a lens type that his scientific competitor Robert Hooke himself had already described.

Van Eijck: And so now the ironical thing is most likely it’s the methods of Robert Hooke himself that Antoni van Leeuwenhoek used.

Intagliata: The findings are in the journal Science Advances. [Tiemen Cocquyt et al., Neutron tomography of van Leeuwenhoek’s microscopes]

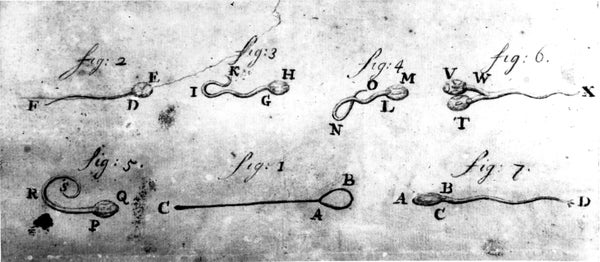

Van Eijck points out that van Leeuwenhoek was still an extremely skilled craftsman and glass grinder—able to build the finest microscopes of his day. And his discoveries of blood cells, sperm cells, parasites and bacteria were altogether extraordinary. It just seems the types of lenses he used to do his work were anything but.

[The above text is a transcript of this podcast.]