The word “archaeology” typically brings to mind crumbling ruins from ancient civilizations—not gleaming rocket ships or high-tech spacecraft. But more than 60 years of space missions have scattered countless artifacts throughout Earth orbit and across the solar system, creating a historic legacy of exploration for current and future generations. Alice Gorman, a researcher at Flinders University in Adelaide, Australia, is one of a few pioneering “space archaeologists” studying the Space Age. She is also author of a new book, Dr Space Junk vs the Universe: Archaeology and the Future (MIT Press), out this October.

Scientific American spoke with Gorman about the emerging discipline of space archaeology, the cultural significance of orbital debris and how to preserve space artifacts as a heritage for all humankind.

[An edited transcript of the interview follows.]

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Credit: MIT Press

What is “space archaeology”? And what does a “space archaeologist” do?

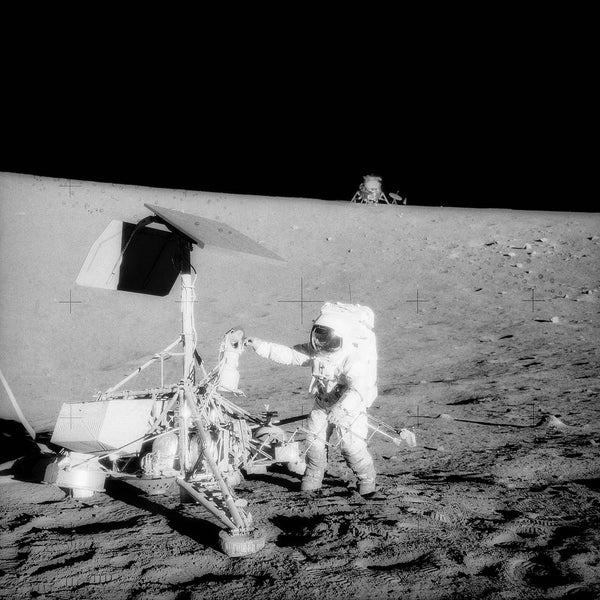

Space archaeology uses the physical material and the places associated with space exploration to learn about the human behaviors behind them. So this covers infrastructure on Earth, objects in Earth orbit and even sites on other worlds. The Apollo lunar landing areas are good examples—to me, those are archaeological sites. And that feeds into the related concept of “space heritage,” which assigns different categories of significance—historical, aesthetic, social, spiritual and scientific—to certain artifacts and sites for past, present or future generations. Much of my work involves gathering the information to help make those judgments. It’s not hard to do, generally—although, because so much of the Space Age predates the Internet, tracking down documentary evidence can be difficult. Sometimes there is literally only one photograph available of something we launched into space. Just one! So I spend some of my time digging through archives, looking through boxes in the attics of houses, stuff like that.

People in the space community generally aren’t used to thinking in this way about preserving or managing the heritage value of their work. But I find if given the opportunity to articulate their own emotional attachment to some of these things—a particular piece of space hardware or product or place—most of these hard-nosed scientists, engineers and astronauts have strong feelings. Giving the aerospace sector more opportunities to value its own heritage is a big part of my mission.

You’re sometimes called Dr. Space Junk, but I get the sense you don’t actually like the term.

That’s right. Even though I strongly identify with that persona, the term “space junk” is problematic. From an archaeological perspective, junk can be very valuable. When we call orbital debris “space junk,” we’re closing off the idea that it might have some positive qualities, now or in the future. Some space junk is still functional—satellites that still have fuel and can still transmit. They’re only junk because no one is using them at this point in time. Not that these things must be gathering and relaying data to be useful; space artifacts can have primarily social rather than scientific functions, like Elon Musk’s now interplanetary red Tesla sports car or Vanguard 1, the oldest satellite [remaining] in space. Most of their value comes from shaping people’s ideas of what space is and how they are connected to it.

In your book, you argue for preserving space junk. But regardless of what we call it, shouldn’t something be done to clean up orbital debris, which can collide with operational satellites and spacecraft?

It depends. We don’t have many good ways of getting stuff out of orbit right now, but someday there could be special little vehicles flying around, pulling dangerous objects down, either to burn up in the atmosphere or to be delivered to Earth. If a piece of debris is not actually a risk to anyone or anything, I do think it’s better—certainly cheaper—left as is.

What about something like Vanguard 1? Why not bring it down and put it in a museum?

I don’t think putting Vanguard 1 or other superlative artifacts in a museum is the best strategy for preserving value.

An artifact’s setting can be an important part of its significance. Some of Vanguard 1’s significance depends on its being the oldest human-made object in orbit. Brought back to Earth, it can’t be the oldest thing in orbit anymore—something else would gain that status. And, in terms of scientific significance, the longer we leave it up there, the more precious it becomes as a resource telling us the effects of long-term exposure to the space environment. We can and do study this remotely, measuring via reflectance how rough Vanguard 1’s once smooth surface is becoming over time. Also, if you put Vanguard 1 in a museum, most people will never see it, only locals or tourists. But left as is, anyone can go look for it in the sky. Now all they would see, at best, would be a little dot of light. But it’s more democratic and accessible, in a sense, up there in orbit. Being in a museum could also endanger it. Financially, all across the world, many museums are in a precarious place. Governments tend to cut funding for them in times of stress, and when that happens, collections can suffer.

Are there any space artifacts or sites that merit special protections?

I’m very worried about lunar sites, particularly those of the Apollo landings. Everyone seems to be talking about going to the moon again, and people have talked about visiting or approaching these places. If we don’t make a solid case for their protection, then some cowboy might just send a rover right up to Apollo 11’s landing site and drive over Armstrong’s and Aldrin’s footprints. Even if they only get close enough for a photo from a distance, that can still stir up lots of lunar dust, which can be very damaging for past exploration sites. So we shouldn’t let these things happen. Some people disagree and seem to think that lunar exploration will come to an end because someone can’t just land directly on top of Tranquility Base. But that’s insane. We still have practically the whole moon at this stage. Prohibitions on visits to heritage sites are not a major imposition on future lunar activities.

Not that there can’t be legitimate reasons to visit these places, like taking samples to study space exposure. If you want to live and work on the moon, knowing which materials are most robust in that environment would be very valuable. But sampling requires very careful planning to maximize the amount of data gained while minimizing damage to the site. On Earth the archaeological principle is to not unnecessarily destroy things and to always leave more for future researchers who may use better, more advanced techniques.