A new study may help answer one of the universe’s biggest mysteries: Why is there more matter than antimatter? That answer, in turn, could explain why everything from atoms to black holes exists.

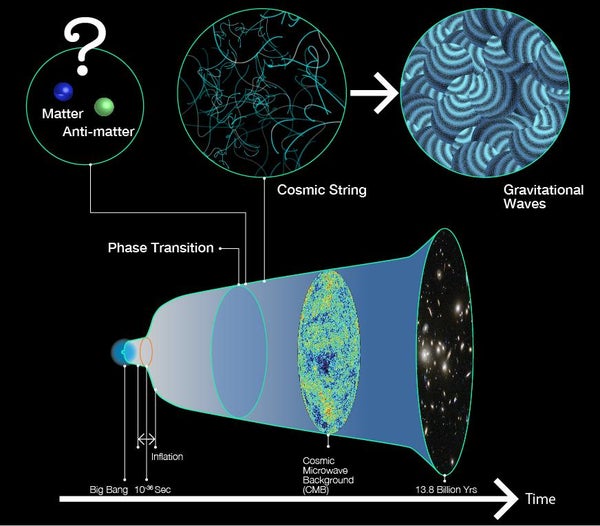

Billions of years ago, soon after the Big Bang, cosmic inflation stretched the tiny seed of our universe and transformed energy into matter. Physicists think inflation initially created the same amount of matter and antimatter, which annihilate each other on contact. But then something happened that tipped the scales in favor of matter, allowing everything we can see and touch to come into existence—and a new study suggests that the explanation is hidden in very slight ripples in space-time.

“If you just start off with an equal component of matter and antimatter, you would just end up with having nothing,” because antimatter and matter have equal but opposite charge, said lead study author Jeff Dror, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, and physics researcher at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. “Everything would just annihilate.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Obviously, everything did not annihilate, but researchers are unsure why. The answer might involve very strange elementary particles known as neutrinos, which don’t have electrical charge and can thus act as either matter or antimatter.

One idea is that about a million years after the Big Bang, the universe cooled and underwent a phase transition, an event similar to how boiling water turns liquid into gas. This phase change prompted decaying neutrinos to create more matter than antimatter by some “small, small amount,” Dror said. But “there are no very simple ways—or almost any ways—to probe [this theory] and understand if it actually occurred in the early universe.”

But Dror and his team, through theoretical models and calculations, figured out a way we might be able to see this phase transition. They proposed that the change would have created extremely long and extremely thin threads of energy called “cosmic strings” that still pervade the universe.

Dror and his team realized that these cosmic strings would most likely create very slight ripples in space-time called gravitational waves. Detect these gravitational waves, and we can discover whether this theory is true.

The strongest gravitational waves in our universe occur when a supernova, or star explosion, happens; when two large stars orbit each other; or when two black holes merge, according to NASA. But the proposed gravitational waves caused by cosmic strings would be much tinier than the ones our instruments have detected before.

However, when the team modeled this hypothetical phase transition under various temperature conditions that could have occurred during this phase transition, they made an encouraging discovery: In all cases, cosmic strings would create gravitational waves that would be detectable by future observatories, such as the European Space Agency’s Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) and proposed Big Bang Observer and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s Deci-hertz Interferometer Gravitational wave Observatory (DECIGO).

“If these strings are produced at sufficiently high energy scales, they will indeed produce gravitational waves that can be detected by planned observatories,” Tanmay Vachaspati, a theoretical physicist at Arizona State University who wasn’t part of the study, told Live Science.

The findings were published Jan. 28 in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Copyright 2020 LiveScience.com, a Future company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.