As a scientist and historian of science, I get asked a lot by friends and family to comment on scientific questions. Are vaccines safe? Is red meat bad for you? How much time do we have left to fix climate change? Many of these matters are not nearly as complicated as they have sometimes been made out to be. Vaccination is broadly safe for most people; eating large amounts of red meat is associated with higher rates of death from a number of cancers; and scientists think we have about a decade left to get greenhouse gas emissions under control and avoid the worst consequences.

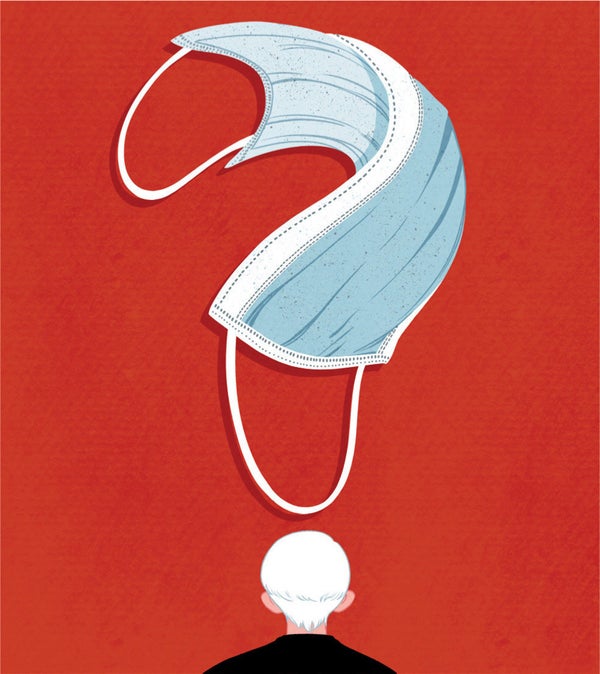

Lately nearly all the questions involve COVID-19—particularly the matter of masks. The argument for wearing them is pretty straightforward: viruses are spread in droplets, which are expelled when an infected person talks, shouts, sings or just breathes. A properly constructed and fitted mask can prevent the spread of those droplets and therefore the spread of the virus. That is why surgeons have been routinely wearing medical-grade masks since the 1960s (and many doctors and nurses wore cloth masks long before then). It is also why in many parts of Asia, people routinely wear masks in public. A flimsy or poorly fitting face covering may not be much use, but—barring the risk of generating a false sense of security—it is unlikely to do harm. So it stands to reason that, when in public, most people should wear masks. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention summarizes: “Masks are recommended as a simple barrier to help prevent respiratory droplets from traveling into the air.... This is called source control.”

So why are people confused? One reason is that we have been getting conflicting messages. In April the World Health Organization told the general public not to mask, while the CDC told us we should. In June the WHO adjusted its guidance to say that the general public should wear nonmedical masks where there was widespread community transmission and physical distancing was difficult. Meanwhile CDC director Robert R. Redfield declared that “cloth face coverings are one of the most powerful weapons we have to slow and stop the spread of the virus—particularly when used universally.” Today government guidance around the globe varies from masks only for sick people to masks mandatory for all.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Why the contradictory messaging? In particular, why did the WHO say in April not to wear masks? At the time, there was a severe shortage of personal protective equipment; the WHO evidently feared that ordinary people would rush out to buy masks, denying them to medical personnel. According to one report, officials were also concerned that widespread masking would lead to a false sense of security, leading people to ignore other safety measures, such as handwashing and self-isolation.

If the WHO had simply said this, there would have been a lot less confusion. But apparently there was another problem. At the time, no direct evidence existed regarding community spread of this particular virus, and most previous studies were done in clinical settings. The WHO put it this way: “There is currently no evidence that wearing a mask (whether medical or other types) by healthy persons in the wider community setting, including universal community masking, can prevent them from infection with respiratory viruses, including COVID-19.”

This is a common pattern in science: conflating the absence of evidence with evidence of absence. It arises from the scientific norm of assuming a default hypothesis of no effect and placing burden of proof of those asserting an affirmative claim. Usually this makes sense: we do not want to overturn established science on the basis of an assertion or speculation. But when public health and safety are at stake, this standard becomes priggish. If we have evidence that something may help—and is unlikely to do harm—there is little excuse for not recommending it. And when there is a mechanistic reason to think it might help, the lack of clinical trials should not be a barrier to acting on mechanistic knowledge. One epidemiologist offered some common sense: “Randomized trials don't support a big effect of face masks, but there is the mechanistic plausibility for face masks to work.... So why not consider it?”

In nearly all areas of science, our evidence is imperfect or incomplete, but this is no excuse not to act on what we know.