Jeffery DelViscio: This is scientific American's science talk podcast. I'm Jeff DelViscio.

If you've ever listened to classic rock you probably heard a swamp Ash guitar. Muddy Waters, Jimmy Page, Bruce Springsteen--they all played swamp Ash Fender Telecasters. But that wood and hence that guitar is now under threat, thanks to climate change.

In a piece in the February Scientific American, Andrea Thompson and Priyanka Runwal write: every winter and spring rains across the central U.S. combine with the snow melt along the Northern reaches of the Mississippi river to inundate the hardwood dominated bottom lands of the lower Mississippi.* When the floodwaters recede and soils dry up in the summer, logging crews move in.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

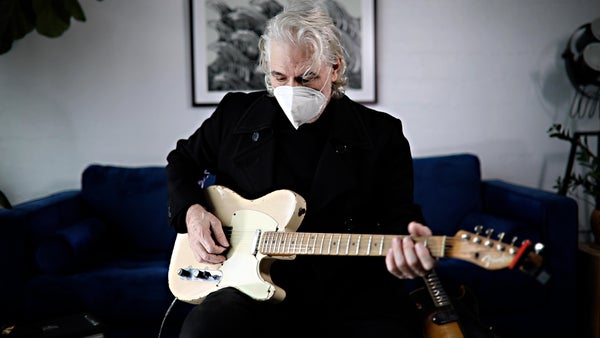

One of their targets has been swamp Ash. These wetland trees have thin-walled cells with large gaps between them creating a low density wood, and some say a special sound that has made it the material of choice for some of the most famous guitar players in rock and roll. Today on the science talk podcast, we chat with Jim Campolingo. He's a veteran guitarist who's recording career started in the mid 1990s.

He's probably best known for creating the group the Little Willies with singer songwriter Nora Jones. Jim talked me through the finer points of swamp Ash and reflected on the threat it's under on a recent rainy morning using his 1959 Telecaster top loader to do the teaching. Here's Jim.

Jim Campilongo: Hi, Jim Campilongo. This is my 59 Fender Telecaster and it's the same design as it was in 1950. So it's kind of like if you went to the Indianapolis 500 and saw a couple of model T's in the race, this is like a model T, but the design was so solid that we still play them. Now, one of the things about a Telecaster is this pickup and that picks up the sound is it's embedded in steel because it was modeled after a lap steel guitar, which fender made before these.

And it has a very, uh, trebbly sound, I guess, for lack of a better word, a very piercing sound, but it's pleasant. Piercing kind of invokes something unpleasant, but you can really manipulate that the tone knob and the volume knob. For example, I'm going to have my tone all the way off and then put it all the way on and you can get this the volume knob is nice too.

You can get kind of a violin, sound. And, uh, so it's a very responsive guitar. The other thing about it, there's many things about it, but is the, it has a, what we call a deep dish here. Okay. Behind, behind the nut. And over the years, uh, players and with great imagination started to incorporate this section and that's our nut and it's called behind the nut.

Because on a Gibson there's not enough real estate to really bend down and raise your pitch. On the tune. Um, women make a fool out of me. I use that. I'm not fretting. I'm getting that from behind the nut, and that's pretty unique of this guitar.

And I've always felt that jazz is really nice on this guitar because it was a very vocal sound. And to me it sounds more like Louis Armstrong and then this kind of, uh, traditional jazz sound. So in a lot of ways, I think a Telecaster is a underrated jazz guitar.

One other thing that's kind of fun is, um, you can, uh, Play with the tuning pegs. And for some reason it's just really user friendly. Um, when, when Leo [Fender] made them, he just got everything that was cheap and accessible. He wanted to make a guitar that. There was, uh, all the materials were available. One of the other innovations he made was that it's a bolt on neck. People didn't do that.

He thought, yeah, if he needed to get the neck fixed or the guitar fix, you can just take the neck off. People don't do that too much. I have some friends who travel, who do, but I don't do it, but it's a bolt on neck. Um, and when it came out, uh, it was $139. Uh, I think the case was another 29, but people made fun of it.

They called it a toilet seat cover with a neck on it. Uh, cause it wasn't ornate, like all the other guitars of that era. Um, and I think it was the first mass produced solid body guitar. It's a solid body. That's the term. Uh, Gretsch [guitars] had messed around with his one, Merle Travis, but Leo was the real pioneer who came up with this guitar that guitar players have loved for 70 years.

Jeffery DelViscio: And so were there solid body guitars before this point, um, was this sort of a relative innovation in terms of what was out there? Um, and you said that toilet seat on the neck, like when did people come around?

Jim Campilongo: I think pretty quick, he had some name players playing, uh, Jimmy Bryant, for example. And, uh, I think they were sensitive enough to see the attributes of it. There was one guy, not a super famous guy. But he switched to a Telecaster and he said, well, it's a good guitar, but it's excellent weapon. And that was one of the reasons he switched over. I mean, he starts swinging this thing around and, you know, you'll clear the stage and I guess this guy played in some really rough spots, but it became popular pretty quickly.

What's interesting is around 1950, I think the first model they made was called the Esquire. And it had one pickup. Then Leo made the two pickup model and called it the broadcaster. But Gretsch had a guitar called the broadcaster. And so there was some kind of cease and desist thing, and he could no longer put a broadcaster decal on the headstock.

So they made for a while, things that are called no casters, because there are Telecaster without a decal. And those are real rare birds. Um, And then, uh, uh, I wish I can't think of his name. The top salesman, uh, is his last name. Uh, he deserves a Don Randall who was like a top sales man and a real idea, man at fender came up with, I think he came up with the term Telecaster and that was in part because television just came out and they wanted to get in on that fad.

So Telecaster it is, and they've been making them since 1950, this one's a 59. And, uh, it was given to me by a guy named John Jensen. And I think he paid $2,000 for it at the time. This is going back. And I Googled this model. This is a toploader or by the way, they call it a toploader because usually on a classic tele the strings go through the body, this one, they go through the bridge.

So you just made them in 59 one year. And I Googled 59 toploaders this morning and I saw one for $27,000. So. It makes me wonder if I should leave it laying around when I go for a walk in the park at a gig, but I still do. And I've traveled the world with this guitar in basically a pillow case. Um, and so far so good. It's my guitar and I want to play it. Um, But anyway, that's kinda this, this, uh, that's the story of, of Telecasters.

Jeffery DelViscio: When you hear that you get the swamp Ash, you know, that, that makes up the body of, of your Telecaster, um, could be threatened to the point of not being able to make these kinds of guitars anymore. What is that? What do you think when you hear that?

Jim Campilongo: Well, of course, I think it's a shame. Um, I know swamp Ash to my knowledge has been getting heavier. Um, and the good light, uh, swamp Ash has been taken now I'm guessing, but pretty close. I think this guitar weighs about six pounds. And when you start getting to eight, nine, 10 pounds, it's it's over a three hour period it gets pretty demanding on one's back and your shoulder. I don't like it. I also like a light guitar because. Well, for lack of a better word, I feel like I dominate it more. Um, if it's light, like I'm the boss, if the things, you know, around 10 pounds, I feel like I got a ball and chain on. So that aspect of the swamp Ash is, you know, it's a concrete thing.

Um, I mean, I kind of look at the bigger picture. I mean, certainly I'm going to miss swamp Ash. They, I know pine is okay. Uh, but it's not based on the whole history of the sound we've been listening to. And whether you know it or not, you know, you've heard it Telecaster. If you've heard, if you've heard the solo on "Stairway to Heaven" or Joe Walsh on "Hotel California," you've heard a Telecaster that will most likely was made out of swamp Ash. So there's that precedent set that we're after and swamp Ash isa part of it.

Jeffery DelViscio: That's great. Do you want to maybe play us a little outro?

Jim Campilongo: One, two, three.

Jeffery DelViscio: For Scientific American's Science Talk podcast. I'm Jeff DelViscio.

Jim Campilongo: Yeah, it's like instead of kicking ass, it's like a kiss on the forehead.