On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

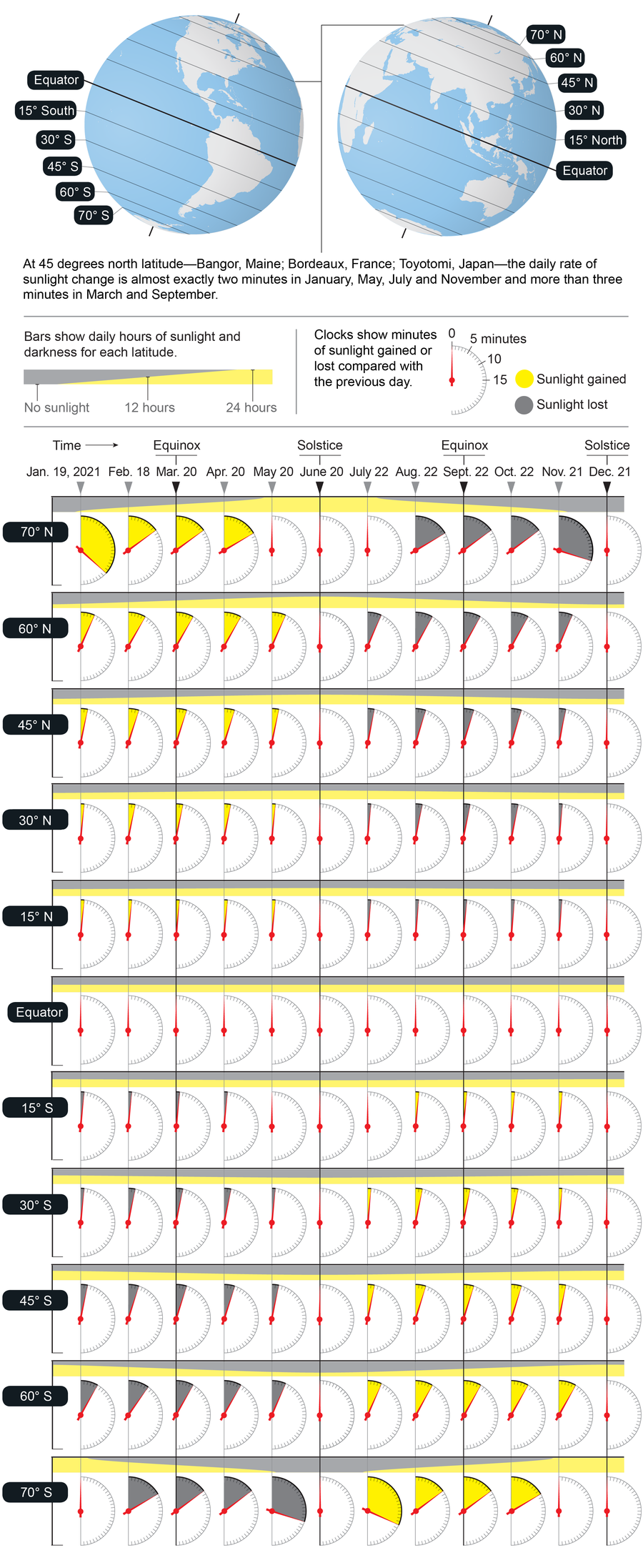

People who live in the midlatitudes enjoy maximum daylight on the summer solstice and put up with maximum darkness on the winter solstice. Between the two extremes, sunlight increases or decreases each day, but the rate of change is not steady. It is least in midsummer and midwinter and greatest around the spring and fall equinoxes. The biggest shifts occur at very high latitude: Just before the period of total darkness (or just after total darkness), the sun is barely above the horizon around solar noon, when the solar elevation changes very slowly, resulting in a large daily difference in daylight minutes lost (or gained). People who live along the equator see no change; they experience a steady 12 hours of day and night throughout the year.

Credit: Jen Christiansen (graphic), Mapping Specialists (globes); Source: NOAA Solar Calculator