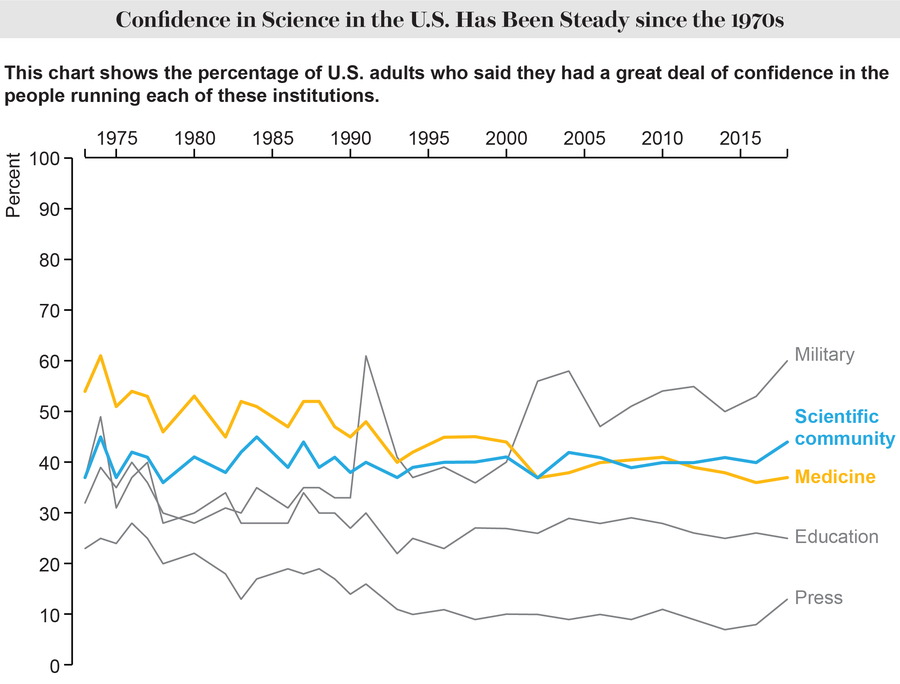

Public trust of the scientific community in the United States is as strong as ever, according to a new poll just released today by the Pew Research Center, confirming polling results dating back to the 1970s. Thirty-eight percent of those polled in Pew’s survey in the U.S. say that they have a lot of trust in scientists to do what is right for the public. Those polled also place a lot of trust in scientific institutions as compared to others in the U.S. Pew’s data show respondents only ranked the military as more trustworthy than scientific institutions, while ranking lower trust in others like the national government, news media and business leaders.

That trust in science is of heightened importance right now, particularly in the U.S., where the novel coronavirus continues to spread and has now killed over 200,000 people. With a lackluster government response, the public has been left on their own with the responsibility to follow guidance and advice provided by public health experts to control the spread of the virus. It’s encouraging to see that multiple polls show the U.S. public still has trust in the scientific community and in medical and government institutions overseeing the virus response.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: General Social Survey, NORC at the University of Chicago

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

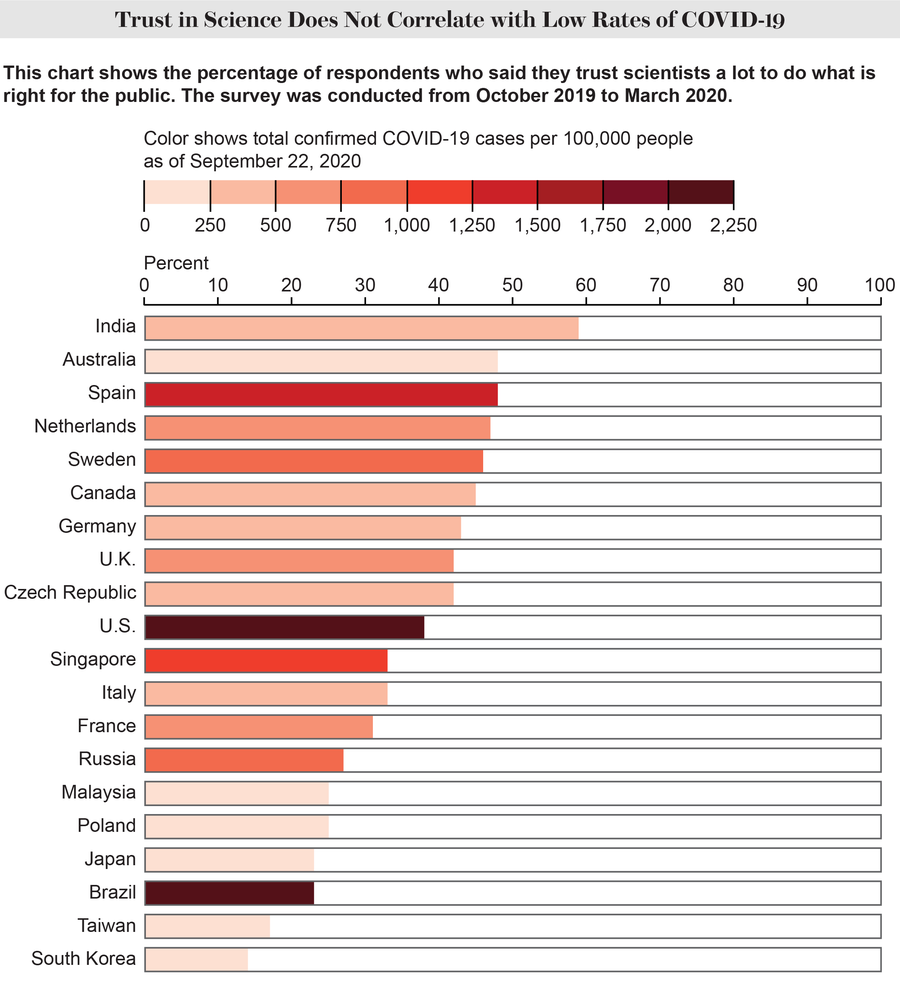

Yet, regardless of the public’s trust in science, the U.S. has the most coronavirus cases and deaths worldwide and one of the highest infection rates. This raises an important question: is public trust in science enough to drive actions at a scale sufficient to effectively combat a nationwide emergency like that of a pandemic? The answer seems to be “no.”

In some countries with far less trust in science (including Taiwan and South Korea, according to the new polling data from Pew), the novel coronavirus has been better contained. It is difficult to know exactly why Taiwan’s and South Korea’s responses seem to be more effective, and it is important to note that comparing coronavirus data among countries is difficult for multiple reasons. But something is different; Taiwan, for instance, has 23 million people, but has seen only 500 cases and seven deaths.

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Sources: Science and Scientists Held in High Esteem across Global Publics. Cary Funk, Alec Tyson, Brian Kennedy and Courtney Johnson. Pew Research Center, September 2020 (survey data); COVID-19 Dashboard, Center for Systems Science and Engineering, Johns Hopkins University (COVID-19 data)

Taiwan attributes its effective response to its memory of the significant effects of the 2003 SARS outbreak in the country. Early recognition of mysterious pneumonia cases in China and suspicions that Beijing was not being transparent about them spurred Taiwan’s government to act quickly. They setup a command center, screened all passengers coming in from Wuhan, China, put in place early travel restrictions, required a 14 day quarantine for all foreign arrivals, and implemented contact tracing and testing weeks before many other countries reacted. Taiwan also has had no problem convincing people to wear masks given the recent memory of the havoc caused by the 2003 SARS outbreak. Of those polled in the Pew survey from Taiwan, only 17 percent of respondents said they had a lot of trust in scientists to do what is right for their country. Taiwan had the second lowest reported trust in scientists in the poll (behind South Korea at 14 percent).

Among the countries polled in Pew’s data, 59 percent of those polled in India said that they trust scientists a lot to do what is right for their country—more than any other country polled in the survey. India currently has over 5.6 million coronavirus cases and is predicted to overtake the U.S. as the nation worst-hit by the virus. A lockdown was imposed in India during March, but a study released by the Indian Council of Medical Research suggests that it was leaky, with transmission occurring as people poured out of cities into rural areas. Low testing rates, poor social protections, and a fragile health care system also have likely led to the spread of the virus in the country.

The U.S., India, South Korea and Taiwan are not the only cases where public trust in science does not match the number of coronavirus cases, deaths or infection rates of a country. Instead, each case seems more dependent on government response (and likely, in the case of Taiwan, a recent memory of the devastation a viral epidemic can cause). Just as with our response to climate change, individual actions do not seem to be solely enough to solve such a large science-based issue.

And if our government’s response affects the spread of the coronavirus more than our individual actions, the U.S. may be in worse trouble than previously thought. While the U.S. public overall trusts the scientific community, many of the country’s responses have been driven by politics rather than scientific evidence. We at the Union of Concerned Scientists have now documented over 160 instances since 2017 where politics have trumped scientific evidence in decisions that affect public health and safety. On the federal government’s response to the coronavirus specifically, we have seen federal scientists ignored, censored, bullied and accused of sedition.

This is all not to say that public trust in science or that wearing a mask when you leave your home are not important; they are both very important so please keep trusting in science and donning those masks! But if we are hoping that such trust in science will be enough to drive the huge collective actions needed to keep the novel coronavirus from spreading, I’m afraid such hope may be misplaced. What we need more than ever is a coordinated and effective science-based response from government leaders. The public trusts the science, but our leaders must too.

We certainly do not have that at this moment.