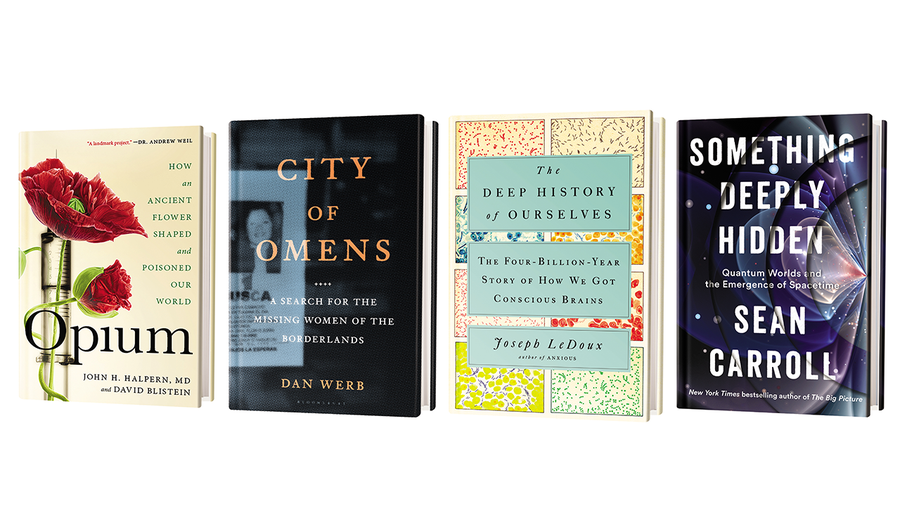

Opium: How an Ancient Flower Shaped and Poisoned Our World

by John H. Halpern and David Blistein

Hachette Books, 2019 ($29)

Humanity's complicated relationship with the opium poppy dates back to our earliest civilizations. Psychiatrist Halpern and writer Blistein trace the plant's origins from ancient Mesopotamia to Greece to China, exploring how it became an effective medicine—and deadly drug. They weave together a history of the flower's medicinal uses, the origins of the opium trade and drug wars, and the modern opioid crisis. It's a story peppered with colorful anecdotes about Hippocrates' use of the drug to treat pain and other ailments, the brazen drug abuser Alexander the Great, and the notorious 19th-century opium dens of San Francisco. Halpern and Blistein decry the view of addiction as a moral failing instead of a disease and detail a long history of misguided and racist drug-enforcement efforts. Although we may never completely stop opioid deaths, they write, better prevention strategies can still save thousands of lives. —Tanya Lewis

City of Omens: A Search for the Missing Women of the Borderlands

by Dan Werb

Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019 ($28)

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Throughout the past decade Tijuana has earned a reputation as one of the world's deadliest cities. Violence, sex trafficking and drug addiction have plagued the region and have made it vulnerable to rapid disease transmission. Epidemiologist Werb joined a research project in 2013 to help investigate the spread of two relentless epidemics in the border town: HIV and homicide. Women in particular were being killed at a staggering rate. In this riveting scientific detective story, Werb investigates the causes of the femicide. He discovers that the virus and murder were symptoms of a larger, more ferocious epidemic targeting Tijuana's women. “It was a multifaceted pathological process closing in on them from all sides simultaneously,” Werb writes. —Sunya Bhutta

The Deep History of Ourselves: The Four-Billion-Year Story of How We Got Conscious Brains

by Joseph LeDoux

Viking, 2019 ($30)

Scientists often don't explain their work clearly. Neuroscientist LeDoux is unlikely to be accused of such neglect in his book, which sets out the entire history of life on Earth. He describes how all living organisms respond to basic needs: threats, food, reproduction, and so on. Survival behaviors, though, are distinct from emotional responses. A true feeling, LeDoux contends, emerges when, say, a threat from the brain's survival circuits is conveyed to “prefrontal” areas, which evolved quite recently in humans to produce an awareness of fear or anxiety, among other emotions. The definition of emotion that LeDoux puts forth raises the provocative question of whether any other animal but humans experiences conscious feelings.—Gary Stix

Something Deeply Hidden: Quantum Worlds and the Emergence of Spacetime

by Sean Carroll

Dutton, 2019 ($29)

Physicists are afraid of quantum mechanics, explains theorist and author Carroll, because they do not understand it—even though it lies at the heart of their discipline. This book is Carroll's unflinching attempt to face that fear, forgoing any mystical hand waving in favor of simply describing what is actually known. It is also an argument for one of the more mind-boggling interpretations of quantum mechanics, the many-worlds theory, which posits that the simplest solution to quantum paradoxes is to assume we live in an ever expanding, many-branched multiverse where every possibility is realized. Something Deeply Hidden is enlightening and refreshingly bold. Is it right? No one yet knows. —Lee Billings