We may now have direct evidence that planets can survive unscathed the violent churn that attends their host star’s death.

Astronomers have spotted signs of an intact giant planet circling a superdense stellar corpse known as a white dwarf, a new study reports.

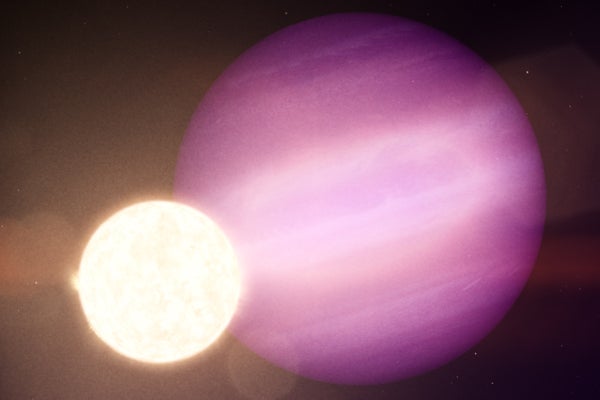

The white dwarf in question, called WD 1856, is part of a three-star system that lies about 80 light-years from Earth. The newly detected, Jupiter-size exoplanet candidate, WD 1856 b, is about seven times larger than the white dwarf and zips around it once every 34 hours.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“WD 1856 b somehow got very close to its white dwarf and managed to stay in one piece," study lead author Andrew Vanderburg, an assistant professor of astronomy at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said in a statement.

“The white dwarf creation process destroys nearby planets, and anything that later gets too close is usually torn apart by the star’s immense gravity,” Vanderburg said. “We still have many questions about how WD 1856 b arrived at its current location without meeting one of those fates.”

The first of its kind (potentially)

Vanderburg and his colleagues found WD 1856 b using NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), which hunts for alien worlds by noting the tiny brightness dips they cause when transiting, or crossing their host stars’ faces from the spacecraft’s perspective.

The team then studied the system in infrared light using NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope shortly before the observatory’s January 2020 decommissioning. The Spitzer data showed that WD 1856 b is emitting no infrared glow of its own, suggesting that the object is a planet rather than a low-mass star or a brown dwarf, a body that straddles the hazy line between planets and stars.

Still, WD 1856 b remains a candidate planet for now, awaiting confirmation by further analyses or observations.

You wouldn’t necessarily expect white dwarfs to be promising targets for TESS and other planet hunters, considering the process that forms them.

When sunlike stars run out of hydrogen fuel, they bloat into red giants that engulf and incinerate anything orbiting nearby. For example, our own sun will destroy Mercury, Venus and perhaps Earth when it becomes a red giant, about 5 billion years from now. Red giants eventually collapse into white dwarfs, which typically pack the mass of our sun into a sphere only slightly bigger than Earth.

It’s therefore safe to say that WD 1856 b didn’t form at its current location; the object would never have survived WD 1856’s red-giant phase. Indeed, the study team’s calculations suggest that the candidate planet must have been born about 50 times farther away from the star than its current location, then migrated in.

“We’ve known for a long time that after white dwarfs are born, distant small objects such as asteroids and comets can scatter inward towards these stars. They’re usually pulled apart by a white dwarf’s strong gravity and turn into a debris disk,” study coauthor Siyi Xu, an assistant astronomer at the international Gemini Observatory in Hawaii, said in the same statement.

“That’s why I was so excited when Andrew told me about this system,” Xu said. “We’ve seen hints that planets could scatter inward, too, but this appears to be the first time we’ve seen a planet that made the whole journey intact.”

It’s unclear what gave WD 1856 b its inward push. Possibilities include nudges from the other two stars in the WD 1856 system and a brief interaction with an intruding “rogue star,” wrote team members in the new study, which was published online today (Sept. 16) in the journal Nature.

But “the most likely case involves several other Jupiter-size bodies close to WD 1856 b’s original orbit,” coauthor Juliette Becker, a planetary scientist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, said in the same statement.

“The gravitational influence of objects that big could easily allow for the instability you’d need to knock a planet inward,” Becker said. “But at this point, we still have more theories than data points.”

No other planets have been spotted in the WD 1856 system, but that doesn’t mean none are there, study team members said.

Rocky planet survivors, too?

WD 1856 b’s apparent existence has exciting consequences for planetary scientists and astrobiologists. For example, if a gas giant can survive a sunlike star’s death, then huddle close enough to the burnt-out corpse to suck up significant warmth, couldn’t a rocky, Earth-like world do so as well?

Vanderburg and other researchers investigated this possibility in a companion paper, which was published today in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. The team, led by Cornell University researchers Lisa Kaltenegger and Ryan MacDonald, used computer modeling to simulate the looks that NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope could get at a hypothetical rocky world orbiting in the “habitable zone” of WD 1856.

The habitable zone is that just-right range of orbital distances where liquid water could be stable on a world’s surface.

The researchers determined that Webb, a $9.8 billion flagship observatory scheduled to launch in October 2021, could spot the signatures of oxygen and carbon dioxide in such a planet’s air after observing just five transits.

“Even more impressively, Webb could detect gas combinations potentially indicating biological activity on such a world in as few as 25 transits,” Kaltenegger, the director of Cornell’s Carl Sagan Institute, said in the same statement.

“WD 1856 b suggests planets may survive white dwarfs’ chaotic histories,” Kaltenegger said. “In the right conditions, those worlds could maintain conditions favorable for life longer than the time scale predicted for Earth. Now we can explore many new intriguing possibilities for worlds orbiting these dead stellar cores.”

Copyright 2020 Space.com, a Future company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.