MOON GAZING

In “Alien Moons,” Rebecca Boyle describes several techniques for detecting moons around exoplanets. While such findings to date are rare, there is another method that she failed to mention: gravitational microlensing. This approach is of value in dense star fields when a star is transited by a planet whose moon happens to be in the plane of the planet’s orbit and alongside it at that time.

David Shander Denver

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

BOYLE REPLIES: Gravitational microlensing is an interesting technique, but it comes with a significant downside, which is that scientists usually have only one chance to use it. Once the planet passes between Earth and some background star, there likely won’t be another opportunity to do follow-up confirmation measurements. For that reason, gravitational microlensing is not well suited to discovering exomoons, although it can be used as a statistical technique to study their frequency. Furthermore, astronomers using this method might never know whether the foreground objects are a small star and a planet or actually a planet and a moon.

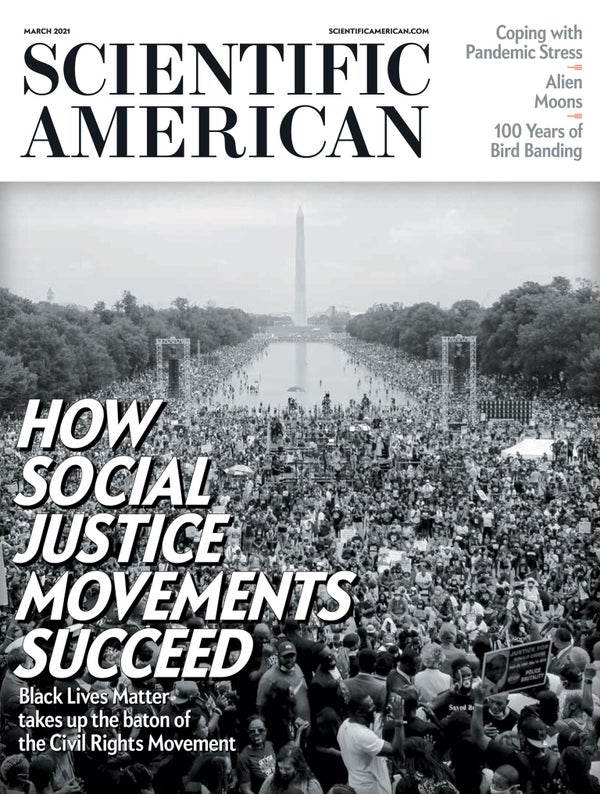

HISTORY IN MOVEMENTS

I read Aldon Morris’s “The Power of Social Justice Movements” with initial skepticism. I was trained as a physicist and had always treated social science as something of a pseudoscience. After reading this excellent article, I see that I was wrong in so many ways. Morris walks us through the process that led to his indigenous perspective theory and compares it with other theories that I previously thought I was in agreement with. I’m not so sure now.

I have seen many of the same things throughout my life that Morris relates in his article, though from the perspective of a white senior currently living in a conservative suburban area near Denver. The death of Elijah McClain and the exoneration of the Aurora, Colo., police officers who perpetrated his death were the catalysts for much of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests in Denver.

It seems that many of us are required to raise our voices for social justice time and again with little to show for it. Morris has reminded us that after all these years of “successful” movements, we still have so far to go. I am encouraged by the volume of the voices that speak for social justice, and there is reason to hope that someday we can get to an equitable society in this country and become that beacon that many wish we were.

GARY WEBSTER Littleton, Colo.

Morris’s article was superb. As a (very) senior American, I lived through the Civil Rights Movement, marches, court rulings, horrific violence perpetrated and continuing to be perpetrated, and now BLM. To have a sociologist describe and explain the growth of academia’s perspective on movements, as well as put this huge—and still painful—part of the U.S.’s story in the spotlight, was enlightening.

LOIS RODENHUIS Dover, N.H.

I appreciated the depth of detail, insight and personal reflection in Morris’s cover story. And I was glad to see the prominence that Scientific American afforded the article: it’s the right time, and this magazine is the right venue for the material.

I know I’m not alone among those in scientific and technical fields in having failed, for far too long, to take necessary hard looks, ask myself hard questions and do the hard work to bring genuine social justice to our professional fields and our country. Now isn’t too late, and I’m glad for your help.

ANDREW BOYKO via e-mail

SCIENCE IN DIPLOMACY

In the March Forum column, Nick Pyenson and Alex Dehgan ably and correctly argue that “The U.S. Needs Scientists in the Diplomatic Corps.” There is another arm of international “diplomacy” in which U.S. scientists and engineers contributed their talents with significant effect: European outposts established not long after World War II, such as that of the Office of Naval Research in London. Its staff of scientists and engineers were, in effect, traveling science and technology journalists who visited mainly U.K. and European laboratories and reported back to the U.S. scientific community through the publication European Scientific Notes. Other components of the U.S. Department of Defense similarly carried out liaison activities in Europe and Asia.

The interactions between U.S. and foreign scientists were extremely successful and exemplify what we can do by employing our scientific talent for international outreach.

HERB HERMAN Distinguished Professor emeritus, Stony Brook University

In 2001 I was posted as one of the National Science Foundation’s (NSF’s) first Embassy Science Fellows at the U.S. embassy in Bern, Switzerland. During that time I visited 20 strongholds in nanotechnology and science and helped with the drafting of the U.S.-Swiss science and technology framework. I was in Bern for a month, and after I returned to NSF, I co-organized some workshops with Swiss professors. Doing so brought our countries and research communities closer.

I think such programs are very beneficial for all countries around the world. Science and engineering indeed have no national borders.

KEN P. CHONG George Washington University

WRITING THROUGH NEGATIVITY

In “Coping with Pandemic Stress,” Melinda Wenner Moyer describes psychological methods to help people whose mental health has declined because of COVID-19. I was relieved to read about the value of writing about negative emotions, though for reasons unrelated to the pandemic. For several years I went through kidney failure, dialysis and related issues. Throughout all that, I kept writing down what I was dealing with. Once I finally got a transplant (just before the pandemic, as luck would have it), I read what I had been writing for all those years and was surprised at how negative so much of it was. On one hand, I had misgivings about the negative tone. But on the other, it still seemed vitally important that I had done this writing and had this record.

Interestingly, I feel no such compulsion to write about the pandemic in the same way. I guess that as abnormal as life now is, it’s still much more normal than my life has been for many years.

JACKIE MILLER via e-mail

THE BOMB AND ME

In “Biden’s Nuclear Challenge” [Science Agenda], the magazine’s editors remind us that we must worry about nuclear war. I happen to have just come across my third grade newspaper, for which I was editor in chief, from February 1951 at P.S. 114 in the Bronx. In the Poetry Corner, a fellow student named George wrote, “Practice, practice every day/ I hope the bomb never comes our way./We know we have to be ready/So let us all be calm and steady.” Seventy years have passed!

JAY M. PASACHOFF Williamstown, Mass.