On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

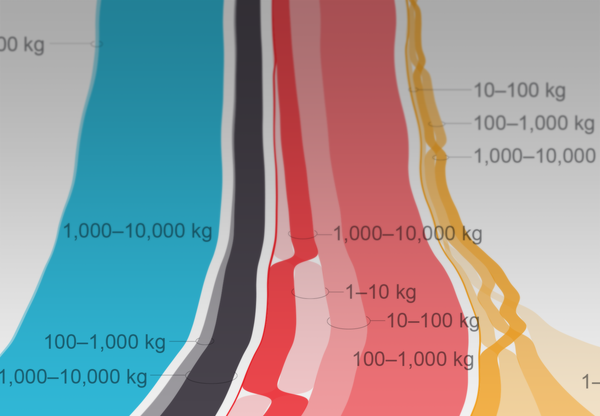

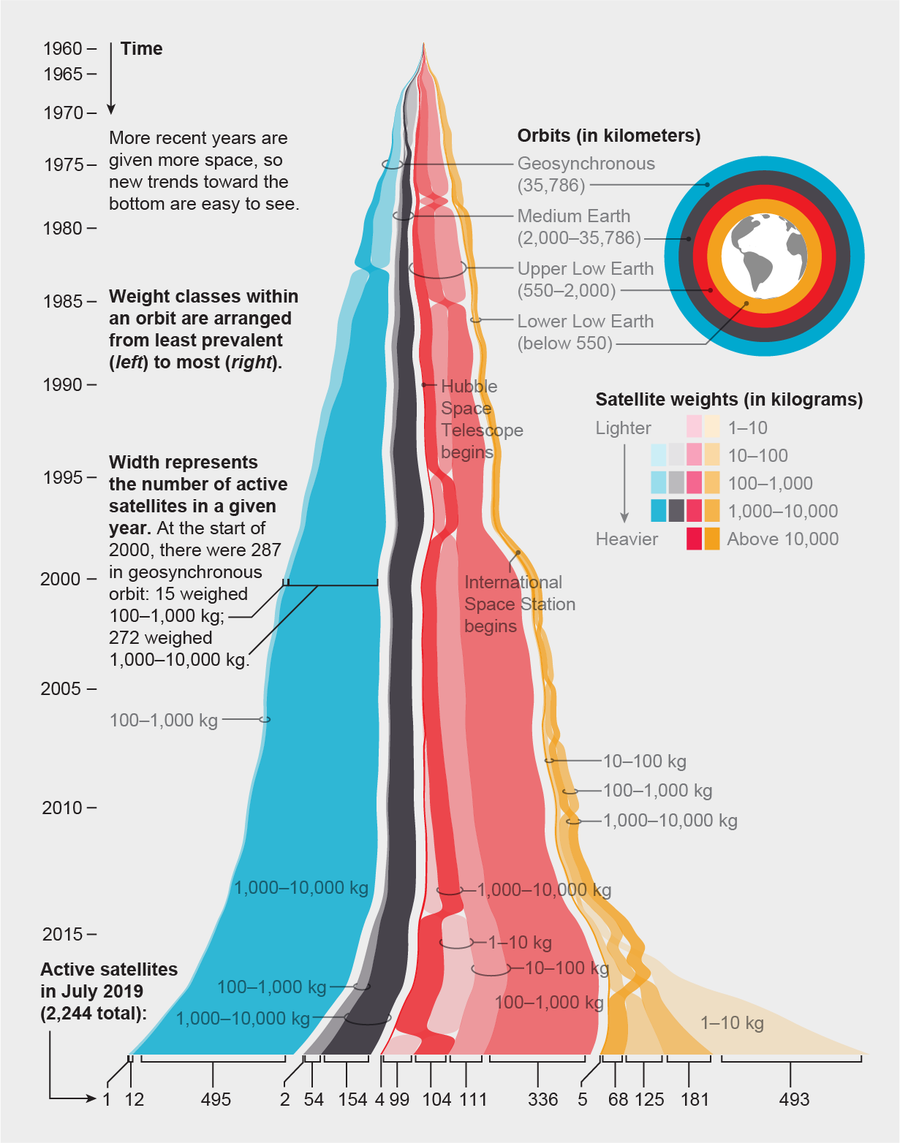

For decades the number of satellites orbiting Earth rose at a gentle pace, but growth has soared recently. By July 2019 more than 2,200 satellites were aloft. In the 1980s and 1990s the action was in geosynchronous orbit (blues), says Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist at the Center for Astrophysics|Harvard & Smithsonian. But now the action is in the lowest Earth orbits (yellows), he says, and increasingly dominated by young companies rather than government, military or academic owners. Today the push is from Starlink—constellations of satellites weighing 260 kilograms, being launched by SpaceX to deliver high-speed Internet.

The uptick started around 2014, stemming largely from CubeSats—diminutive satellites, each lighter than 12 kilograms, that were lofted in groups. They are fulfilling a desire to observe changes on Earth every day. CubeSats could reveal, for example, how people were moving around Wuhan, China, during the coronavirus outbreak. And instead of Google Earth showing driveways with cars from 10 years ago, it could display vehicles purchased last week.

Credit: Nadieh Bremer; Source: Jonathan McDowell’s Space Report, 2019