Ganymede, get ready for your close-up.

No probe has gotten a good view of Jupiter’s largest moon since 2000, when NASA’s Galileo spacecraft swung past the strange world, which is the largest moon in the whole solar system. But on Monday (June 7), at 1:35 p.m. EDT (1735 GMT), NASA’s Juno spacecraft will skim just 645 miles (1,038 kilometers) above Ganymede’s surface, gathering a host of observations as it does so.

“Juno carries a suite of sensitive instruments capable of seeing Ganymede in ways never before possible," principal investigator Scott Bolton, a space scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, said in a NASA statement. “By flying so close, we will bring the exploration of Ganymede into the 21st century.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Ganymede is a fascinating world for scientists. Despite its status as a moon, it’s larger than the tiny planet Mercury and is the only moon to sport a magnetic field, a bubble of charged particles dubbed a magnetosphere. Until now, the only spacecraft to get a good look at Ganymede were NASA’s twin Voyager probes in 1979 and the Galileo spacecraft, which flew past the moon in 2000.

The massive Jovian moon will be a main target of the European Space Agency’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer mission, known as JUICE, which is due to launch next year and arrive in the Jupiter system in 2029. But that’s a long time to wait, and Juno, which launched in 2011, carries significantly more powerful technology than the Voyagers and Galileo spacecraft did.

So scientists are thrilled to make use of the Juno opportunity. During the flyby, several of the spacecraft’s instruments will observe Ganymede, including three different cameras, radio instruments, the Ultraviolet Spectrograph (UVS), the Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) instruments and the Microwave Radiometer (MWR).

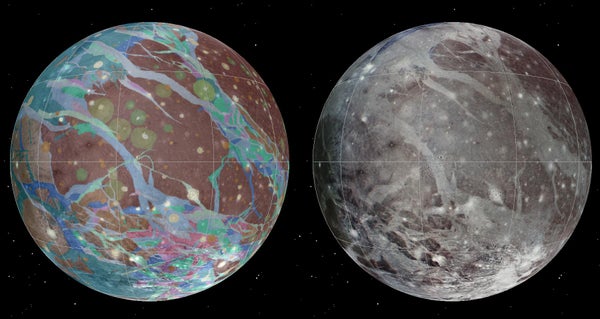

That last instrument’s measurements are particularly intriguing for scientists, who hope to use them to identify the different ingredients in the lighter and darker patches of Ganymede’s ice shell.

And among the cameras studying the moon will be, of course, the same JunoCam that has snapped such stunning portraits of the gas giant throughout the mission. However, because the icy moon will appear and fade in just 25 minutes, mission scientists expect the instrument will be able to take only five images of Ganymede during the encounter.

But despite the excitement of the unusual moon flyby, Juno scientists can’t lose sight of a milestone coming close on the heels of the Ganymede investigation, when the spacecraft makes another flyby of its usual target, Jupiter itself.

“Literally every second counts,” Matt Johnson, Juno mission manager at JPL, said in the same statement. “On Monday, we are going to race past Ganymede at almost 12 miles per second (19 kilometers per second). Less than 24 hours later, we’re performing our 33rd science pass of Jupiter—screaming low over the cloud tops, at about 36 miles per second (58 kilometers per second).

That means Juno will zoom by Ganymede at a speed of about 43,200 mph (69,523 kph) and then whip around Jupiter at a whopping 129,600 mph (208,571 kph). But Juno’s ready for it, Johnson said.

“It is going to be a wild ride.”

Copyright 2021 Space.com, a Future company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.